Welcome to Freeze Frame, our look back at moments from this week in automotive history

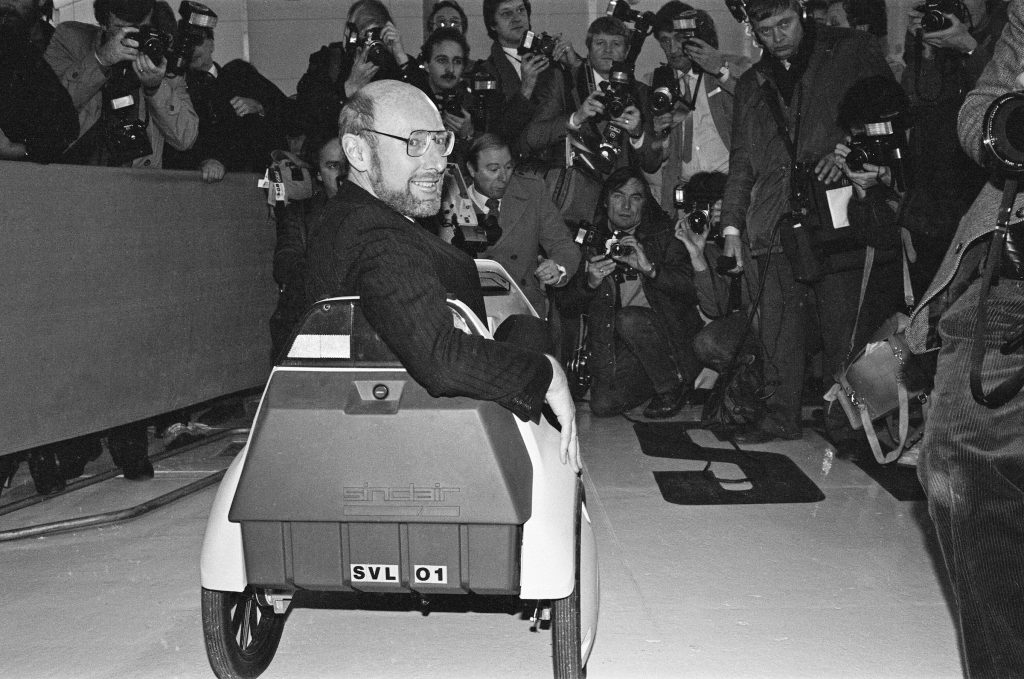

29 March 1985 – Sinclair C5 production suspended

It’s customary for projects like Sir Clive Sinclair’s C5 to be described as “ahead of their time”, but sometimes it’s the case that there was simply no good time for a particular product.

And so it was that full-scale production of the C5 was halted on March 29th of 1985, barely three months after its launch in early January that year. Production would resume, at just 10 per cent of original levels, and the vehicle disappeared entirely by August, marking it down as one of the great failures on the journey to change the way people get about.

The idea that commuters would sit reclined, their heads level with other vehicles’ bumpers and have to contribute some of the propulsion themselves to assist the C5’s third-of-a-horsepower motor, seems amusingly short-sighted today. Aside from electric bicycles, the closest in concept to the C5 we’ve come since are cars like the Renault Twizy and Citroën Ami. The former remains rare outside of warm tourist destinations and the latter’s performance is limited; likeable as they are, neither is likely to change the world.

Sir Clive came up with the idea as early as the 1970s, while surrounded by technology in his company, Sinclair Radionics. Together with one of his employees, Chris Curry, he developed a slimline electric motor, but things really took off in 1979 when Sinclair hired Tony Wood Rogers to carry out consultancy work into a “personal electric vehicle” with a 30mph top speed, dubbed the C1.

There was solid evidence that such a vehicle might work, much as there is for short range vehicles today: at the time, the average car journey was just 13 miles and moped commuters travelled only 6 miles. At the right price – £500 was mooted, a quarter that of a Fiat 126 in the early 1980s and around £2200 today – there was certainly potential.

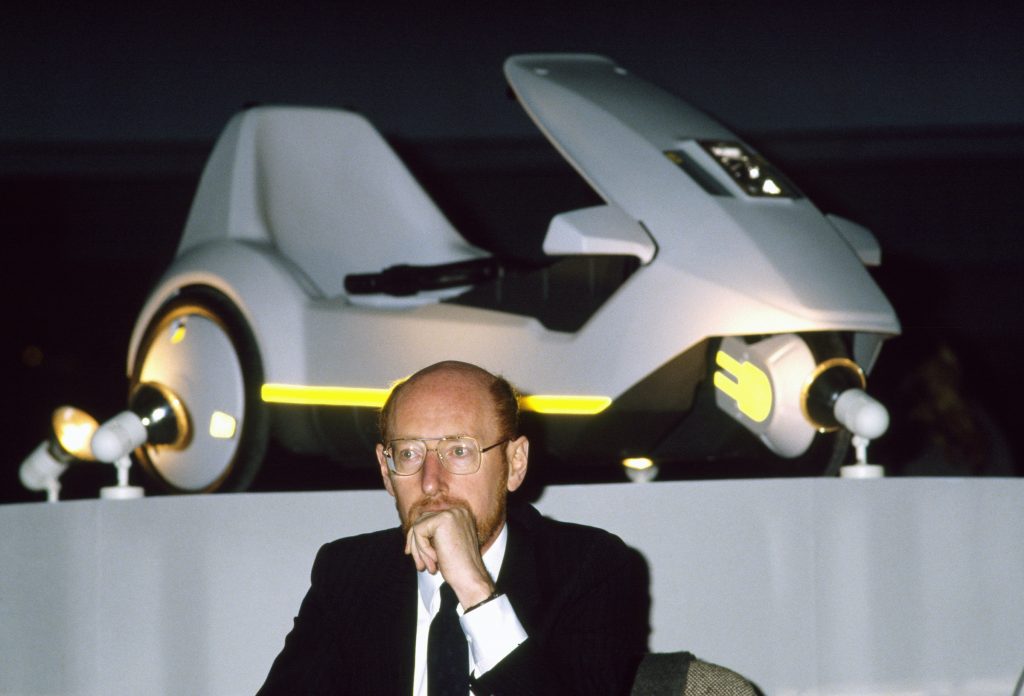

Development began in earnest at the University of Exeter in 1982, with Sinclair drafting in Ogle Design (best known for the Mini-based SX1000, the Reliant Scimitar and the Bond Bug) to pen the C1. It proved a tough process though, not to mention expensive, and in March 1983 Sinclair sold some of his shares in Sinclair Research, raising £12 million and forming a new company, Sinclair Vehicles.

The project got a boost in late 1983 when the British government passed legislation exempting a new class of vehicle, electrically assisted pedal cycles, from requiring a driving license or helmet. Such vehicles would be limited to 15mph – legislation that still influences the top speed of electrically-assisted bicycles today. Sinclair chose to adapt his project to fit this new legislation, and throughout 1984, development progressed. Lotus was drafted in for testing, industrial designer Gus Desbarats brought in to refine Ogle’s shape, and vacuum cleaner manufacturer Hoover would build the car – by now known as the C5 – at its plant in Wales.

By the time of its glitzy launch in 1985 the price had dropped to £399 (approximately £1200 today) and C5s would be sold via mail order. But things begin to fall apart quickly, with poor reviews in the press (not helped by faults with many of the test units), users feeling more than a little vulnerable around traffic (and breathing in fumes to boot), and a lack of weatherproofing. After an initial flurry of sales, interest quickly slowed to a trickle.

The bottom line? Hoover got cold feet at the slow sales and resulting unpaid debts. Production ceased, Sinclair Vehicles – after a name change that September – went into receivership, and many unsold C5s were eventually sold for less than a fifth their original price.

Yet Britain loves an underdog. Today a small band of enthusiasts gladly repair and recommission the C5s that remain. There is, it may not surprise you to learn, a lively Facebook group with nearly 1700 members dedicated to the car, and a website covering all the information you’d need to repair and maintain a C5 – including making use of 3D printing to remanufacture and improve upon original components.

Sir Clive is no doubt proud that his vehicle has achieved this in its afterlife, and if the C5 can’t be described as being ahead of its time, he can at least take solace that it certainly hasn’t been forgotten.

Read more

Freeze Frame: First road race at Donington Park

Life’s a beach: The new generation taking on Bruce Meyer’s dune buggy

If you want this Hustler kit car, you’ll need to Sprint