Welcome to Freeze Frame, our look back at moments from this week in automotive history.

31 July 1971 – Apollo 15’s Lunar Roving Vehicle takes first drive on the moon

Sure, your lifted ‘n’ snorkelled Land Rover Discovery makes a formidable off-road device, capable of wading through fords and clambering over boulders on its oversized tyres. But no vehicle better qualifies for the term “off roader” than one designed to drive so far away from roads that it will forever reside on another celestial body.

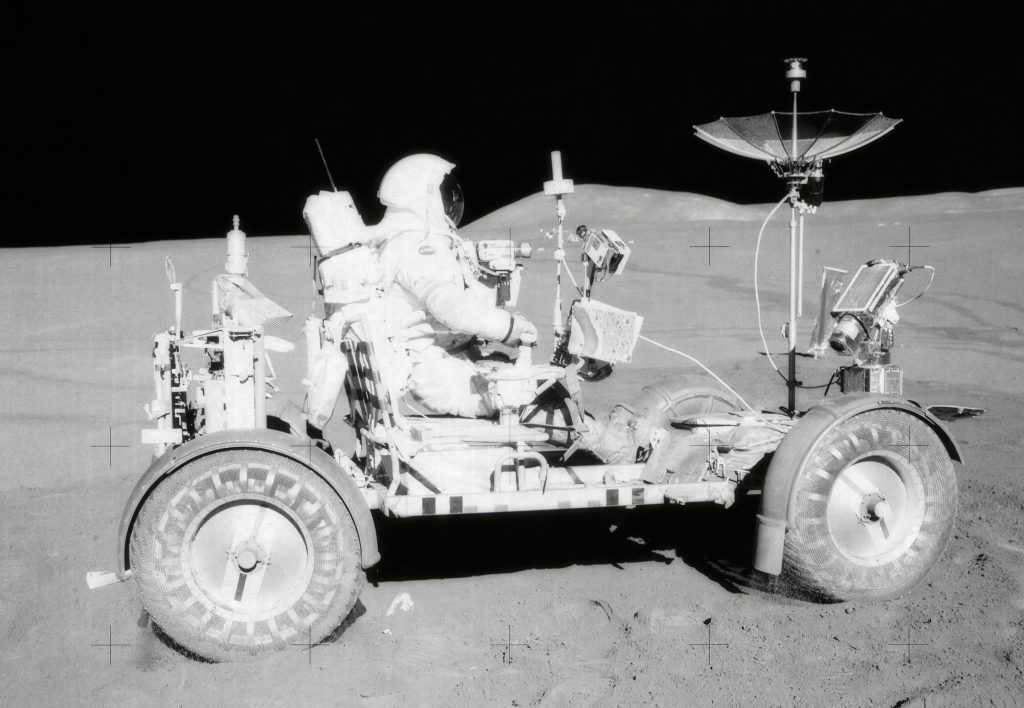

Fifty years ago, on July 31, 1971, Commanders David Scott and James Irwin became the first people to drive a vehicle on the surface of the moon, during the fourth crewed lunar landing mission, Apollo 15.

Their automobile, the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV, and often called the lunar rover), was the first of three to be used on the lunar surface. By its nature the LRVs are among the most interesting vehicles ever designed, required to operate in circumstances literally alien to those of any other car.

The LRV’s primary purpose was to extend the distance astronauts could venture during their mission, and extend it did: on Apollo 15, Scott and Irwin drove a total of 27.8km in just over three hours, albeit at a maximum distance from the lander of only 5km – a precaution to ensure the crew could still return should the LRV break down.

Not that the LRV wasn’t extensively tested, albeit not in circumstances identical to those found on the moon. The need for a land vehicle was recognised in the early 1960s, and practical studies began as early as 1962 – though early designs anticipated the need for a pressurised vehicle.

Research showed that special wheels and tyres would be required (if you have a basic understanding of physics, you’ll realise why a regular pneumatic tyre might not be ideal…). The LRV eventually used a spun aluminium hub, and a zinc-coated, steel-wire woven tyre arrangement with titanium chevrons for traction.

Likewise, propulsion would need to be electric, owing to the absence of combustible gas in the thin lunar atmosphere, so each wheel got a quarter-horsepower motor sending power through a harmonic reduction gear. Both axles were steered, while the chassis was an aluminium alloy frame, hinged in the middle so the vehicle could be stored in the lunar module. And of course, it was little more than a kart in design, far simpler, cheaper and easier to launch into orbit than a pressurised vehicle.

What you might not realise is that it was incredibly light: just 210kg. And that’s on Earth, too – at little more than 16 per cent of the Earth’s gravity, the LRV weighed just 34kg on the moon, with a 490kg (or 78kg on the moon) payload capacity. And of course, its pilots would be similarly weightless, meaning plenty of spare capacity for samples.

Controls might have confused the average driver, or maybe appeared blissfully simple; the LRV accelerated, braked and steered with a T-shaped handle that operated much like a joystick.

(If you’d like to replicate the control method today, simply hook up a joypad to a Playstation 3 and fire up Gran Turismo 6, which actually featured a lunar exploration mission – one of the stranger driving experiences ever offered in a videogame…)

It was special then, but the LRV was not cheap. The original Boeing contract came in at $19 million in 1971, but ran over budget to $38 million, around quarter of a billion dollars or £180 million at current exchange rates. Still, that looks like good value compared to the $5.5 billion that Jeff Bezos recently spent to arc over the Earth at 65 miles for four minutes or so, and its benefits to the US space programme were considerable.

“The Lunar Rover proved to be the reliable, safe and flexible lunar exploration vehicle we expected it to be,” said Harrison Schmitt, from the later Apollo 17 mission. “Without it, the major scientific discoveries of Apollo 15, 16, and 17 would not have been possible; and our current understanding of lunar evolution would not have been possible.”

Read more

Freeze Frame: End of an era for Renault-based Dacia

Cars That Time Forgot: 1963 Chrysler Turbine

Your slow-motion video guide to how a carburettor works

I once had the honour of interviewing James Irwin for BBC local radio, and we talked about the LRV. He joked that he and David Scott were just the ‘delivery drivers’ for a decidedly low-mileage car!