It’s said that necessity is the mother of invention. For Philipp Eissner, it was his wish to make a meaningful gift for his father’s birthday.

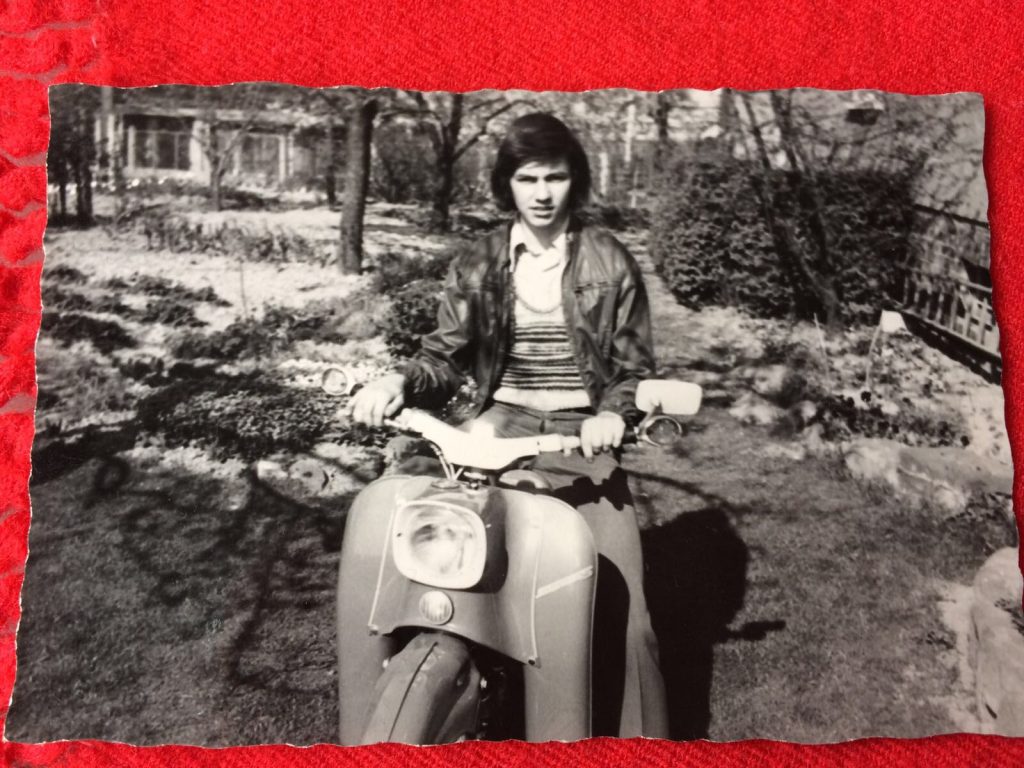

“Most people associate their first car with feelings of freedom, independence and individuality,” says Philipp, who was inspired to make a floor lamp using parts salvaged from a burnt orange Simson Schwalbe moped. It was the same model, colour and year of manufacture as the one his father rode as a young man.

“The automobile is an incredibly powerful and emotive object, but in life, these loyal companions are often thoughtlessly exchanged, replaced or forgotten. Much later they become a reminder of youth, love stories and exciting vacations.”

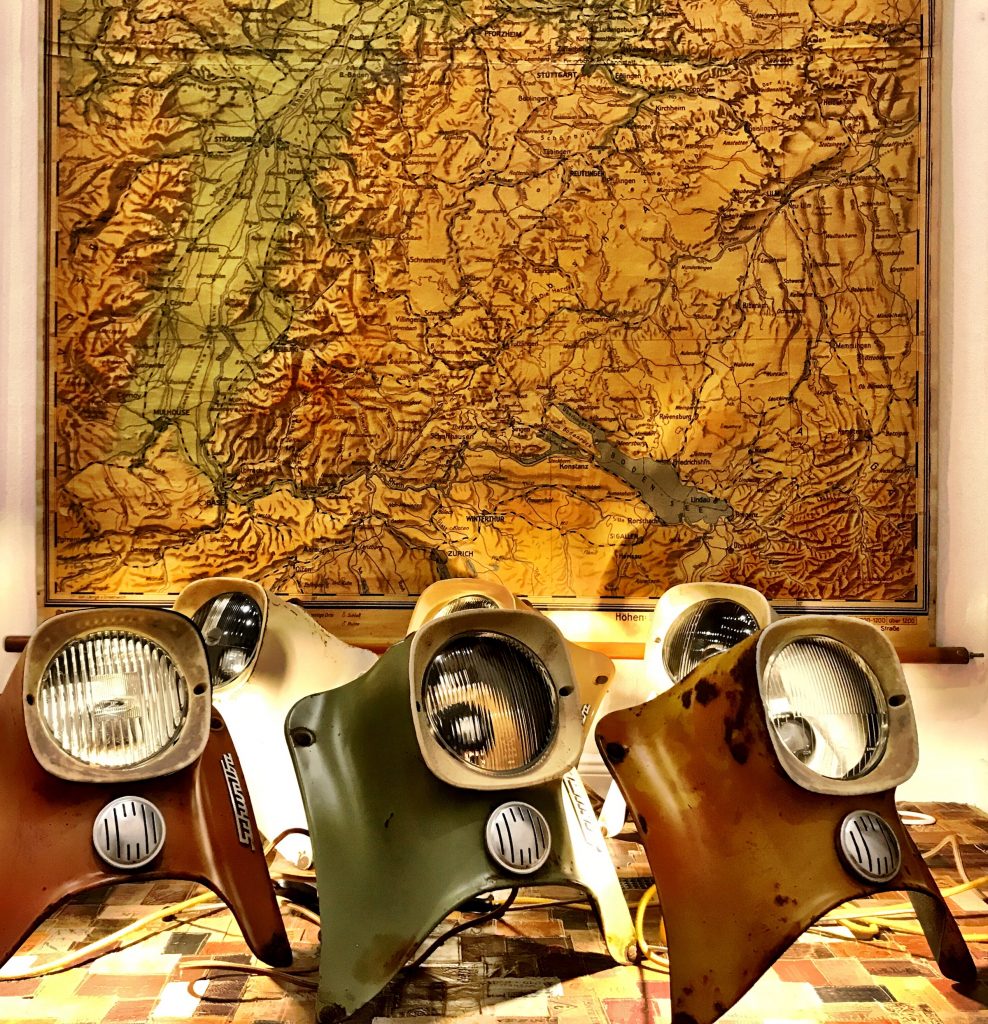

The biggest design challenge was creating an “aesthetic connection” between the old original parts – which included a weathered front body panel, headlight and tachometer – and the “dismal looking” modern electrical components. Unsatisfied with the results he was getting, Philipp started again several times, but ultimately a birthday can’t be postponed. “It took a couple of night shifts, but the lamp was ready on time.”

Tarnished by rust that softens its functional form, the lamp sits in his father’s music room. Considered “a member of the family” as well as the symbolic light-bulb moment for Philipp’s upcycled vintage lamp business, Illoomatic. The gift was meant to be a one off creative project, but today his designs can be found in homes all over the world.

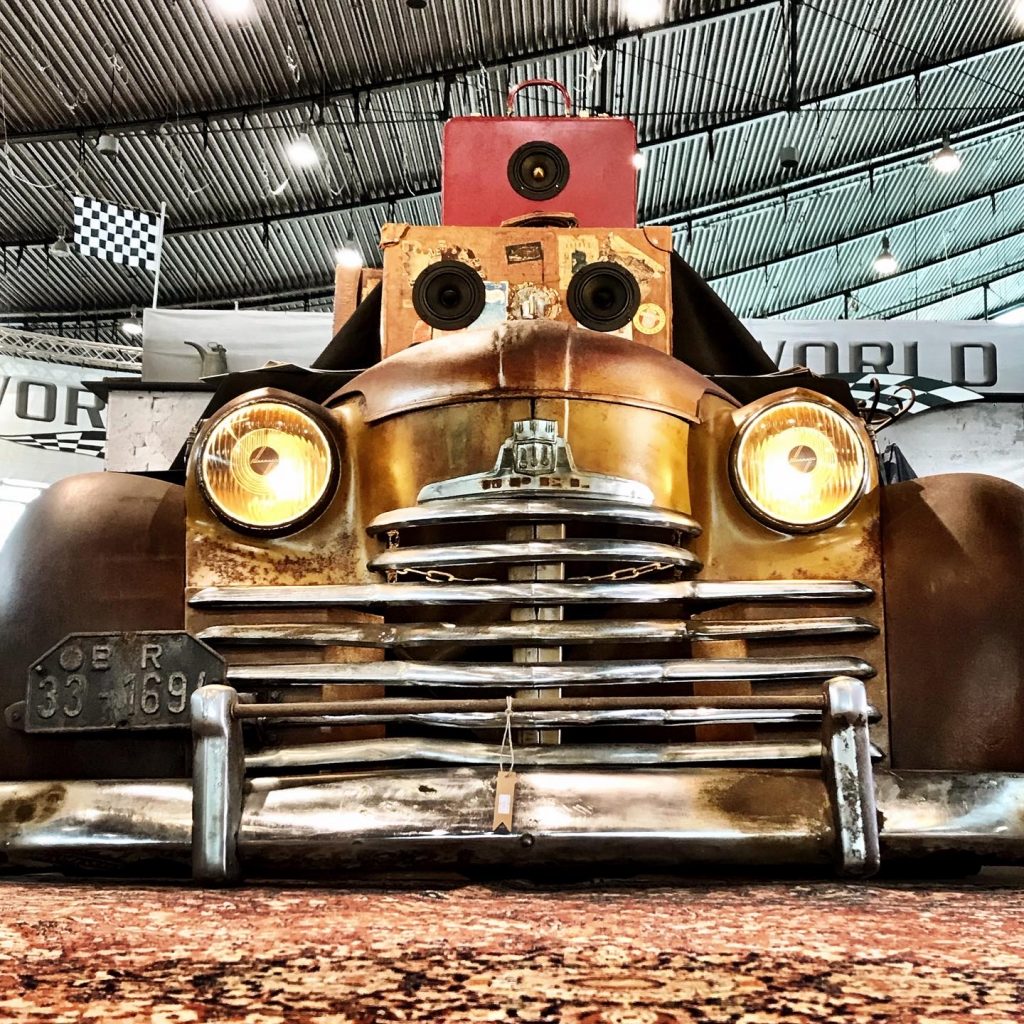

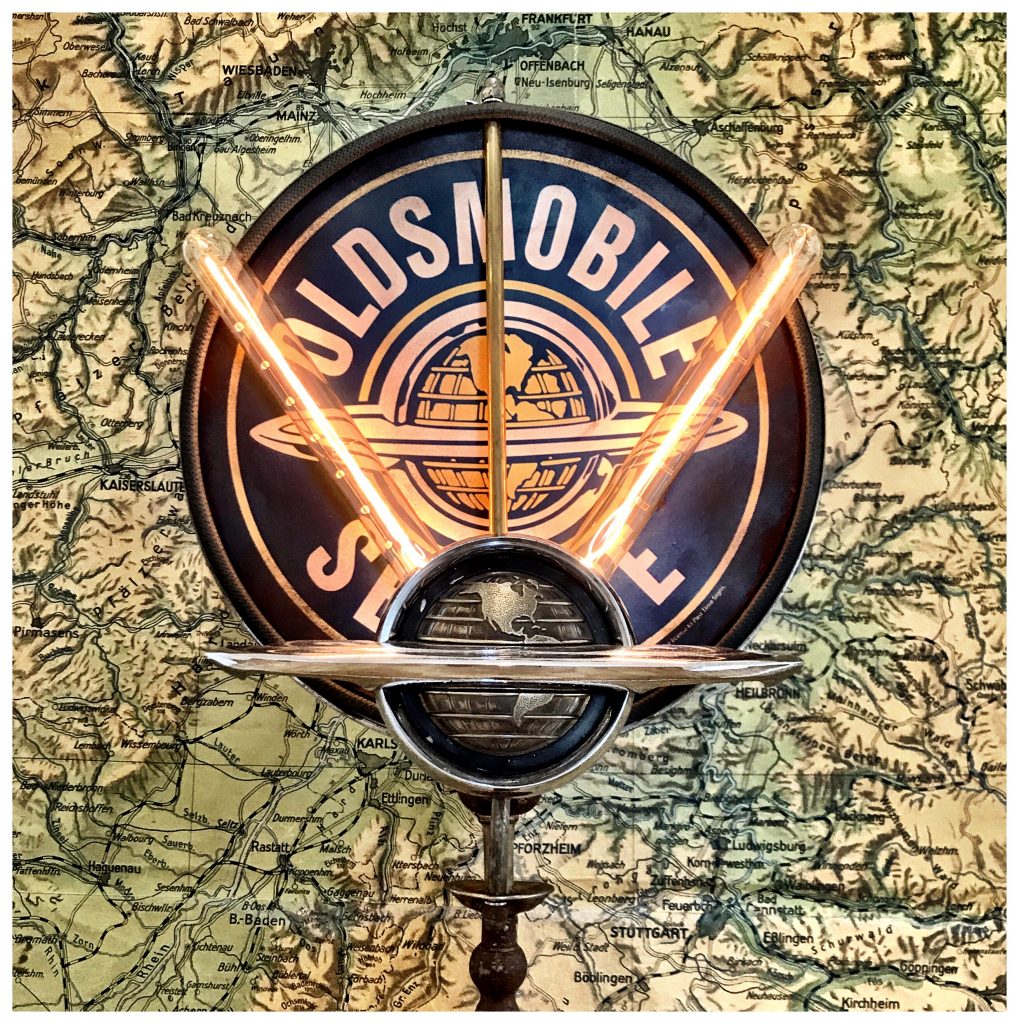

Utilising skills he’s acquired whilst restoring his own classic cars, Philipp has configured lamps out of a plethora of automotive artefacts that includes the front of a 1950 Opel Olympia, taillights salvaged from a Ford Taunus 12M and 1961 DKW Junior de Luxe, and hubcaps rescued from a 1953 Oldsmobile Super 88 and VW Beetle. As a nifty finishing touch, Philipp often attaches a car key to the end of the on/off chord to serve as a handle, and he has a soft-spot for anything American and manufactured between the thirties and fifties. “These legends are the most iconic styled cars of all time, all the crazy trim pieces are an ocean of endless inspiration.”

To bring his recycled masterpieces to life, Philipp requires a “very specific world” in which he feels able to “get caught up” in his creative thoughts. That world is his home in Stuttgart, Germany, and what part of it he works in will depend on his mood.

“I have an extensive 120-year-old vaulted cellar under my house in which I store piles of parts and old sheet metal,” says Philipp. “There are a lot of half-finished projects down there because I rarely build a single lamp from start to finish before I start the next one. There are countless arrangements of parts that I have put together wildly to let the look of possible combinations work on me.”

When he craves a less-cluttered environment, Philipp relocates to the lighter and brighter realms of his above-ground living space. It’s here that completed lamps are given his final seal of approval after being moved between various rooms over the course of a few days. “I like the rough environment of my parts collection and a lot of rust in my focus, but I also need a structured view to evaluate the effect of the lamps.”

With up to five projects on the go at once, Philipp employs the “groovy psychedelic bass soaked retro sound” of stoner rock music to elevate his concentration levels, but says there’s no set path to a finished product because it’s dictated by what he’s been able to find whilst scouting for parts online, or during an expedition to a “car cemetery”, which involves travelling to Scandinavia or North America. “There are no such magical places in Germany anymore,” he says. “Years ago, it was considered garbage and nobody was interested, so they were cleared and renatured. Luckily the wild or private car cemeteries that are left are secret to the scene, they are not available with a google business listing or navigation coordinates.”

It’s only possible to visit these places, says Philipp, if you’re part of a network of urbexers (a type of urban explorer) who share the unwritten moral code that they will not “adjust, rob or manipulate” the locations they explore or the items within them.

“To be very clear: I don’t even steal a small screw from a wild car junkyard. These places are a mirror of impermanence and the few that do still exist are being gradually dissolved, disbanded and evacuated – which is where I step in. I then get the opportunity to remove parts from the vehicles that can no longer find a buyer, before sadly, the rest ends in the scrap press.

“With this I close the circle to the code. I support keeping the magic and character of such places alive as long as possible, and only become active at the last moment before these places disappear forever. Unfortunately, I can’t save everything and sometimes that makes you melancholy.”

From time to time, Philipp accepts commissions, but only if the parts he has been asked to work with have been sourced from an automotive object manufactured before 1970. He also refuses to use objects that have been restored or repainted. “The original condition is the most important aspect for me. It shows the real history and traces of life. Decay is part of the world, and part of creating new. My lamps form a kind of intermediate step that freezes this state.”

Now in its fifth year, Illoomatic remains a part-time passion project for Philipp, a packaging engineer. If he were to rely on it as his sole source of income, he fears it would destroy the fun. “I would have to think of the kind of mainstream product that supports the business economically, this is impossible with what I am doing here. My creations and ideas are far too important to me than doing tough calculations on them. When I build my lamps I associate relaxation and joy on the one hand, but also personal challenge and the constant struggle with myself and my visions.”

So what is his vision for the future? “I’ve never worked with classic motorcycle parts,” says Philipp.

“There were incredibly beautiful designs at Harley-Davidson and Indian Motorcycle in the thirties and fifties but parts are rare and coveted. I don’t want to compete with people that own the last existing vehicles. I’m planning a series called “Motor City Icons” that will be dedicated to American cars made in the forties, but communist vehicles from the former Soviet Union also fascinate me. They were beautiful vehicles at that time and were almost completely hidden from the rest of the world.”

“For many, it is not enough to just look at pictures or movies with their favourite classic cars. The old-timer scene thrives on romance because the soul of an object is simply never there with a brand new item of any kind.”

Also read

Hard Craft: Jake Yorath, graphic designer and illustrator

Making history with Crosthwaite & Gardiner

Why America is falling in love with the Austin-Healey Frogeye Sprite – again