This interview with Martin Brundle is taken from Drivers on Drivers: Motorsport greats on their rivals, teammates and heroes, published by Porter Press International. The hardback book is priced £30, £11 of which goes to Hope for Tomorrow cancer charity from every copy purchased direct from www.porterpress.co.uk

Who was your favourite teammate?

“Ah, that would be Mark Blundell, undoubtedly. We were very close and had a lot of fun together. We were like blood brothers. In sports car racing, you have to work with each other, to trust each other and leave the ego behind a little bit.

“And you know, if you’re in a Le Mans 24-hour race, you need to know that the other driver won’t be bouncing across the kerbs if you’ve agreed not to use them, or ground it, or be bouncing off backmarkers, and you’ve got to set the car up to fit three different sizes of driver and [suit different] driving styles and what have you. So, it’s a complex business, motorsport teammates.”

Who do you think was the bravest?

“Well, what does bravery mean in a racing car? You can be a risk-taker. Does that equate to bravery, as such, or is that a bit foolhardy? I will go with Stefan Bellof on that. He did appear to be absolutely fearless and had a trust and a belief in his own abilities. Obviously, he flipped the Porsche at the Nürburgring. And he’d had a few big shunts. He did live life on the edge. You’ve got to question whether that’s bravery or foolhardiness. Back in the day, in terms of teammates, I think it would have to be Bellof who had that devil-may-care attitude.

“I think true bravery would have been in the 1950s and ’60s when there were no seatbelts, no crash barriers, often just trees, and the mortality rate was massive. I think that’s the true meaning of bravery in a racing car, because you know your chances of dying, just through mechanical failure, or coming across something on the track, are incredibly high. When you hear those stories about how the drivers hoped to get thrown out of the cars as their best chance of surviving, thinking that when you step into a car, knowing that may well happen to you, then that’s, for me, the true meaning of driving bravery.”

Do you have any favourite stories about fellow drivers?

“Well, yes, you have a few laughs along the way, there’s no doubt about it. With some of them, I guess it’s what goes on the road, stays on the road.

“Mark Blundell and I were at Imola when we were teammates. I finished third that day for Ligier but he crashed on the first lap. So I’d had a great day and I got a great big trophy, which is sitting in my cabinet today. It was 1993 and I was larking around pulling the handbrake on as we were leaving the péage, the toll at the autopista, and a policeman tried to put his little red bat out to stop us and we didn’t know what that meant at the time.

“Eventually we got pulled over on the motorway and they pulled Mark out of the car. I’m sitting in the car with my wife and my trainer, and Mark’s beginning to get money out of his pocket to pay a fine. When he gave his name, they said, in broken English, ‘You just finished third in the Grand Prix at Imola,’ and Mark suddenly twigged. He realised they’d got the names mixed up and came running back to the car and said, ‘Gimme the trophy, gimme the trophy.’ And he goes marching over with this massive trophy from Imola, and shows it to them: ‘Yeah, yeah, me in third place.’ Then I saw the cash coming back out of the window and a handshake and off we went!

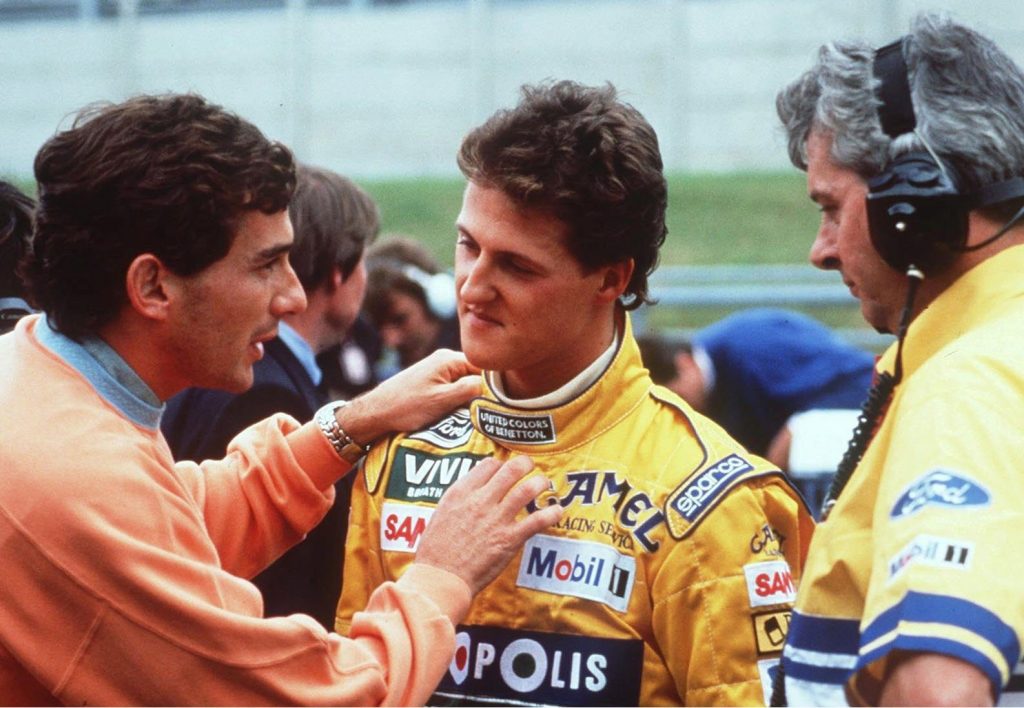

“I remember picking up Michael Schumacher in my Jet Ranger helicopter one day. We were flying to Silverstone and we went over Blenheim Palace. And Michael said, ‘England’s beautiful. I had no idea. I thought England was ugly.’ OK! I think he thought Blenheim Palace was probably somebody’s rather nice house and garden.

“I was thinking about it later on. Why did he suddenly say that? We were flying over the beautiful green countryside of the UK, which I knew so well. And then I realised that his experience of England at that point had been Heathrow, the M1 and Silverstone paddock, basically. And I realised he had a very concrete view of the UK.

“Michael was good fun. We used to joke about him being first out of the taxi and last into the bar, and all that sort of thing. But he was a good guy. And yeah, we had some fun together.

“There was the one with Mark Blundell in the private jet when we were both reading the paper on the way home, pretending the other one wasn’t there after we’d had an incident together on track at Estoril. But Blundell had the last laugh because I went to get on a plane in Nagoya one night to go to Australia. I had a First Class ticket. I handed my ticket in and the lady said to me, in sort of Japanese English, ‘You’re already on the plane.’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m not because I’m here. I’m standing here.’ ‘No, you’re already on the plane.’ We walked on and Mark Blundell was sat in my seat in First Class. He’d told everybody the story, so they all raised a glass of Champagne to me. I spent the night in 32J at the back of the plane, in Mark’s seat because he wouldn’t shift. So he very much had the last laugh in my First Class seat from Nagoya to Adelaide.”

What are your memories of Ayrton Senna? He was ultra-competitive, of course, but broke the rules a bit. In your F3 season together, he tried to take you off once or twice. It was so extraordinary: he had the ability and yet he felt he had to also behave like that.

“Ayrton had the greatest God-given talent I’ve ever seen. It was just natural with him, it was just easy for him. He talked about Monaco, being out of the car watching himself driving, he got into such a rhythm, which I understand. I know that feeling, but I’ve never experienced it to the extreme where you imagine you’re watching yourself, but you do get into a bit of a trance around a place like Monaco in a Formula One car, as you’re just bouncing from bump to kerb to manhole cover and grazing the barriers and you get into an incredible rhythm. So I understand what he means but he had another level.

“I remember an experience in Formula Three: it’s a very long story, but it sums him up. We had a race at Silverstone in the rain. I took off from second on the grid; he was on pole, which often happened, and then I overtook him. I went down to Stowe, and it was treacherous conditions. He went sailing down the outside into Stowe Corner when it was a really fast right-hander. I saw him and I thought, ‘At sea, you wouldn’t want to be out there.’ I navigated the corner very nicely on the racing line. He went right around the outside and came out in the lead, in front of me.

“That was the karting line. I never did karting; I did banger racing when I was young. In karting – I used to have to save up for the magazine, let alone the kart – it’s established that you often actually go off the racing line where the rubber makes the track slick and all that, but this was an extreme example of that, all the way around the outside of Stowe in the pouring rain.

“The race was red-flagged because a guy called Enrique Mansilla had a big crash. So when we regrouped to head out for the second part of the race, I thought, ‘I’m going to try Senna’s line.’ I went down the outside into Stowe. This was the lap to the grid for the restart. Hit the biggest puddle of water, aquaplaned, went down the grass, just kept it out of the bank, grazed the barriers, survived it, got back to the grid. This time Senna beat me away. He finished first and I finished second, and on the podium I said to him, ‘Your line into Stowe didn’t work in the second part of the race, did it?’ Then he said, ‘I don’t know. I didn’t try it. It was too wet. There was too much standing water.’

“The whole track looked like it was flooded. So he kind of had that sixth sense. I often say Senna knew where the grip was before and during a corner, and mere mortals like ourselves knew where the grip was during and after a corner.

“That’s why he was so awesome in the qualifying days with the turbocharged cars and qualifying tyres, which was an adventure from the first corner to the last corner. You’ve suddenly got 400 or 500 horsepower more with the turbos [turned up] and a set of tyres that’s good for five miles – and you’ve got to get the best out of them. So it’s feeling your way round, really, with 1300 horsepower…

“He had this gift and I think it showed up through so many of his greatest wins – his first victory in Estoril in the Lotus [in 1985], for example. So he had this God-given talent. He was a paradox. He was one of the first guys that would think of driving you off the road. And then the first guy to jump out of the car and run back and check that you were OK. He had a competitive spirit that was fearsome, but he also had a human side to him.

“The day he died, we were all shocked. I remember the day Jim Clark died because I was with my dad on a rally. But the day Senna died as a Formula One driver, we all thought, ‘Well, if it can happen to him, it can happen to anybody,’ just as I’m sure all the guys did back in the ’60s when Jim Clark lost his life.”

How did Schumacher compare to Senna?

‘I would say Senna was driven from the heart and Schumacher driven from the head. Michael came at it in a different way. He wasn’t emotionally driven at all. He worked incredibly hard. I don’t think he’d got quite the natural gift of driving or the speed of Ayrton, not quite, but he worked much harder in galvanising everybody in the team around him, everything was pointed at him. And he delivered on track, so they loved him. You forget that everybody in, for example, Formula One is competitive, whether it’s the truckie, the mechanics, the new guys in the team, the old hands – everybody in a team is super-competitive. And of course, if you’re winning, then it points at you. Michael was just extremely good in the car and out of the car to make sure everything was pointing in his direction and then just delivered.

“He had the speed and critically he had the fitness. He turned up in Formula One off the back of an era when we were used to protecting tyres, brakes, clutches, gearboxes, engines… just generally you had to sort of babysit a Formula One car to get it to the end: there were very, very high rates of unreliability. Michael turned up as the cars were getting more robust and much stronger, and could drive every corner of every lap absolutely flat-out. He just moved the game on, frankly. So he was the right man for the right era, and was smart enough to make the most of it.”

And finally, how about a few thoughts on Nigel Mansell?

“Nigel, what a character! Most sports people I’ve met over the decades – I would say the vast percentage, and I definitely fell into this category – you’re driven because you’re constantly dissatisfied with what you’ve achieved or how you drove the car, how you read this race or whatever. I’m sure [it’s true] whichever sport you’re in and it just drives you to be better and better and better by being completely dissatisfied with what you’ve achieved at all times. You end up delivering something that other people can’t imagine how you do it: you drive a Formula One car around Monaco in qualifying, you do 240mph down the Mulsanne Straight, before the chicanes [were added], in the pouring rain in the middle of the night. It’s one of those things you do that felt absolutely normal but are obviously extraordinary feats for sports people. That’s basically how you drive yourself.

“There are a few percent, a smaller percentage of people, who have a supreme self-confidence and that was Nigel, for me, in terms of his belief. A very strong man. And again, the right man for the right time because the early ’90s cars were so unbelievably physical. They had no power steering on them; they were unbelievably physical cars to drive.

“I remember stepping in for Nigel at Spa in 1988, when he had chickenpox, in the Williams Judd and they gave me a steering wheel that looked like a doughnut. I literally stepped in at the last minute. I sat in Nigel’s seat, got in and they put the steering wheel on. I’m like, ‘What is this?’ I could barely turn the wheel to get it out of the garage. It was Nigel’s steering wheel, a tiny little thing because he was so physically strong, and you had to be because there was no balancing up of driver weights back then, so Nigel was carrying many, many kilos more than an Alain Prost, for example.

“They were such brutal cars to drive and Nigel’s confidence and sheer strength and determination made him the right man for the time. His junior racing career was fairly lacklustre in many respects but he ended up being a World Champion through sheer guts, determination and self-belief, and speed. He had the speed and the bravery to go with it. I’m not sure there was a huge amount of finesse but there was certainly some great delivery from Nigel. Yeah, he was a remarkable individual.”

Read more

“I want to find out for myself” – I was there the day Ayrton Senna went rallying

British touring stars: When the Capri, SD1 and Cosworth ruled saloon car racing

Peter Stevens: Designing the Jaguar XJR-15 road-going Le Mans racer – in a car park after work