Editor’s note: Tom Barnard worked at Auto Express magazine, from 1996-2004, part of the ‘golden age’ of spyshots. Spy photographers were in a constant battle to outwit the car companies and the prize was a big pay cheque. These are the stories from the photographers and editors at that time.

Most car photographers will go to great lengths to make their subject look pretty. Lights will be placed with precision and hours will be spent experimenting with exposure settings.

But some of the best-paid car photographers in the world took pictures of fast-moving cars covered in what look like bin bags. At night. From a vantage point up a tree.

These are the pictures which the car makers don’t – usually – want you to see. They are of prototypes which haven’t been announced officially but have to be tested for years before they go on sale. And for car fans and rival manufacturers, they have long been a source of fascination. And before the rise of the internet, getting a great scoop was a proven way of selling car magazines.

But the traditional spy shot is dying out. Car makers are getting better at hiding new models away and CGI technology means the media can create far more realistic-looking images of future models – without having to pay a photographer to sit in a tree in the Arctic at midnight.

The master of car spyshots

It wasn’t always that way. The spy shot industry pioneer was the legendary Hans Lehmann. Now 83 (and comfortably retired), the German trained as a news photographer and, as luck would have it, while ‘off duty’ he photographed a new Volkswagen out testing near his family home, in Hamburg. It turned out to be the EA97 project, which was supposed to replace the Beetle but never went into production. He found a ready market for the pictures in German tabloids and realised it could be more lucrative than taking pictures of the oberbürgermeister (mayor) cutting the ribbon at a new supermarket.

Pretty soon these images of disguised future models were the mainstay of the news pages on motoring magazines, with rival publications battling to secure shots of soon-to-be-launched big selling models. “There’s no doubt that scoop stories sold mags,” says Steve Fowler, an editor who was at the helm of Autocar between 2002 and 2003 and is now in charge of rival Auto Express. “As a result, the magazines would pay thousands for a good picture of an interesting car, especially if it was an exclusive. This meant the photographers would go to extremes to get those shots.”

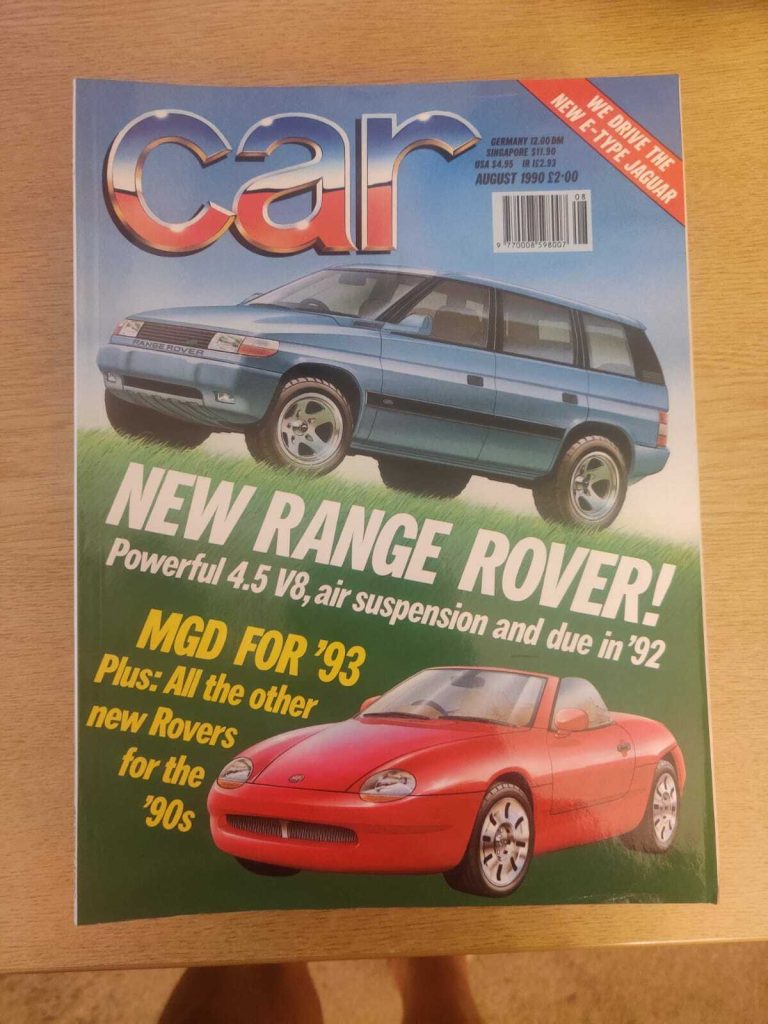

The battle for the best scoops really hotted up in 1992 when the established magazines Auto Express and Autocar & Motor slugged it out for sales with a new publication called Carweek. A new monthly, Complete Car, also launched in 1994 to take on the long-established Car magazine.

Magazines battle for readers

Hilton Holloway worked on the news desk of Carweek before moving to Car and then Autocar. “In those days we used to get the pictures sent in the post as it was pre-digital,” he reminds us. “Most of the time the photographer would know exactly what the car was, but occasionally they wouldn’t have a clue and we’d have to do our own detective work.”

This could be trying to the trace the registration number if it was a UK car, or scouring through pictures in brochures looking for a shared door handle or wheel design. It was complicated further because British engineering firms such as Lotus and Ricardo would work on cars for clients based in markets which would never be sold in the UK. Amateur spy photographers would hide in ditches and lurk behind fences outside the workshops of the likes of Lotus and Ricardo, or around the test tracks where vehicles would undergo testing, including Millbrook in Bedfordshire and MIRA in Nuneaton, all in the hope they could capture a prototype which would bring a big pay day.

Besides the entrances to engineering companies, test tracks and the ever-popular Nürburgring, the favourite ‘hunting grounds’ for the spies were the places where car makers venture to test for smooth running in extreme climates. These are usually the artic circle in the Nordics, Death Valley in the US and Alpine routes in Europe. But photographers hiding up a tree in the hope of stealing a shot as cars leave frozen lakes and deserts had to endure the same extremes of temperature as the prototypes.

The locals make these locations even more inhospitable. In places such as Arjeplog in northern Sweden, the area’s economy has revolved around car testing since the 1970s. The lake freezes and becomes a test track from October to April. The hotels, restaurants and workshops are full of engineers and news of any ‘spy’ activity soon spreads. The likes of Lehmann was broadly unwelcome and a room for the night was out of the question, so the snooping snappers had to build a network of accommodating B&B owners who’d turn a blind eye.

In other locations, the photographers would find themselves being detained by the police and having to hand over films. Although he didn’t want to revisit those days for this story, Lehmann has previously explained how he’d hide film rolls before the authorities arrived, and hand over dummy rolls, so his trips weren’t wasted.

An accidental spy photographer

Brenda Priddy had to endure plenty of difficulty too. Christened the “Queen of Spyshots”, the American started to take spy pictures at the beginning of the ‘boom’ years in 1992 after she spotted some camouflaged Ford Mustangs in a supermarket car park. As a part-time wedding photographer, she had cameras in her car so grabbed some shots. They turned out to be hot property and made the cover of a US motoring magazine, Automobile.

Priddy then realised she lived on a regular test drive route taken by Ford engineers, and she had a disguise which was even more effective than the getup covering the still-secret cars – she was a young mum pushing a pram. None of them suspected a thing.

This success led to her ditching the day job and ‘spying’ full time, with Death Valley becoming her regular hunting ground. Every summer Priddy would spend several weeks sitting it out, patiently awaiting the arrival of the secret prototypes, renting motel rooms and apartments which were sometimes literally above the car maker’s engineering hub.

She remembers the days well, when we speak: “On rare occasions I would be detained by the police, but here in the US, they knew better than to demand my film or memory cards. But the test engineers would attempt to use intimidation: I have been yelled at, my camera was pushed into my face and the force broke my nose, I was hit by a prototype in a parking lot and test cars have attempted to run me off the road.” But Priddy wasn’t going to be intimidated, especially as she wasn’t doing anything wrong. “I never ran,” she says with pride.

Priddy also had a unique method of nobbling the competition. “When my son was 10 or 12, he’d like to find Lehmann in the desert, and then hang out with him for a bit. I considered it a great way to distract Hans!”

Manufacturers also had ways to avoid spy photographers. Most testing of early prototypes will only move from a rolling road and out into the open while safely behind the barbed wire of a test track. This wasn’t enough to put off the photographers though, who simply bought ladders to look over a fence, or climb a tree. This led to a constant battle between the test track security and the snappers, with ever taller fences and screens being put in place.

Hanging from helicopters to scoop the MG F

Millbrook, an industry proving ground in Bedfordshire, had another weapon to discourage pictures being taken over its fence – it informed the magazines’ road test teams that they would be banned from using the facility if spyshots of cars on its premises were published. This was rigidly enforced – both Carweek and Auto Express were thrown out permanently after publishing pictures of the Rolls Royce Silver Seraph on a handling track.

But fences were no match for the cunning of editors looking to secure the next big scoop. “The peak frenzy of spyshots must have when we were all trying to get the first pictures of the MG F in the early 1990s,” says Michael Harvey, who was then the news editor of Autocar. “All of the mags were desperate for a proper picture but none of the usual sources had got one. So we decided to hire a helicopter and fly over Rover’s Gaydon R&D centre.”

With a photographer hanging out of the door armed with a powerful zoom lens, the chopper did two circuits of the track before returning to base, mainly limited by the cost – Autocar’s budget could only stretch to an hour’s hire.

“Irritatingly, the MG F just wasn’t out on track at the time, so we never did get the ‘money shot’. We did get some pictures of the still-secret Rover 400 though, and a very angry letter from the bosses at Rover followed shortly afterwards,” remembers Harvey, who now edits The Road Rat magazine.

Other than big fences, protective locals and stroppy letters, the car makers’ greatest defence was disguise. In the early days it was simply the removal of the badges and some tape, but the masking became ever more elaborate; the first Range Rover was disguised with ‘VELAR’ badges and registrations which hid the geographical origin of the vehicle. In the 1990s, the Freelander had to be hidden underneath a butchered body of a Maestro van. Now, Land Rover will use ‘distress patterns’ of stripes, shapes and matte paint which hide subtleties of a car’s shape, and even make it difficult for automated cameras to focus.

Pictures without this disguise were particularly valuable, but they rarely came from cars which were spotted out on the road and had to be smuggled out of secret locations. Anyone caught using a camera would be sacked instantly, but many took the risk as the rewards were substantial.

Hagerty’s own editor, James Mills, managed what was known as the ‘hot metal’ department at the weekly Auto Express, from 1994 to 1999. It was considered strategically important. “In the age of electronic point-of-sale data,” recalls Mills, “we had a good indication of magazine sales week by week, and spyshots sold magazines. Our department ended up hoovering up much of the editorial budget because big scoops meant big sales in the newsagents.”

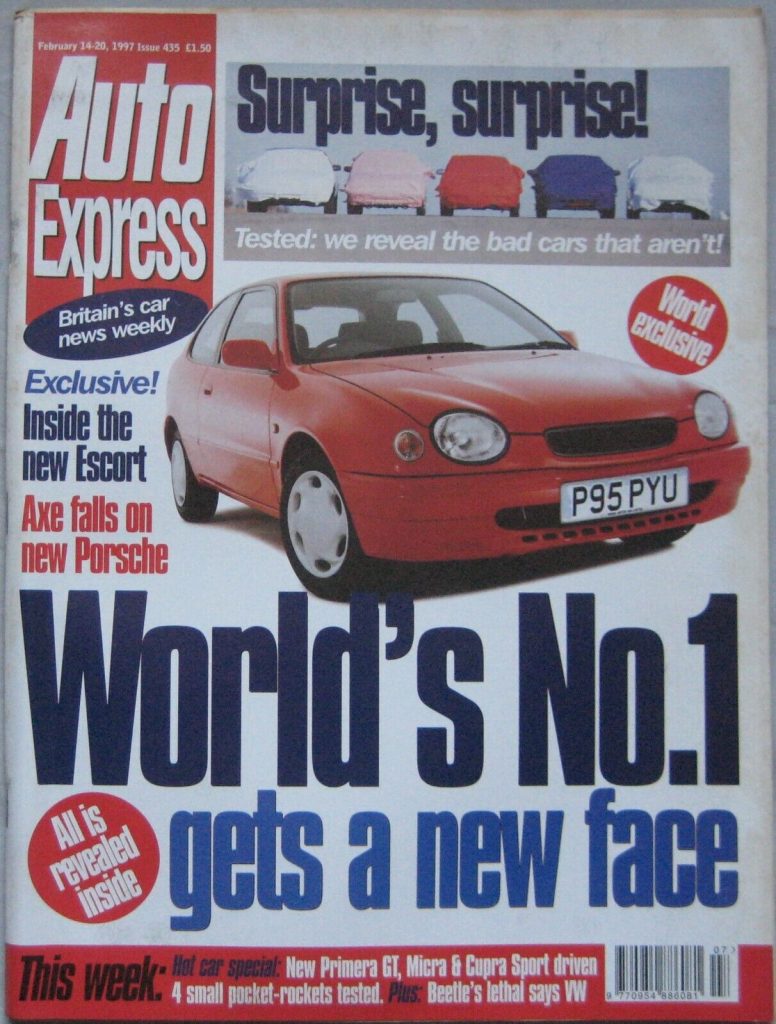

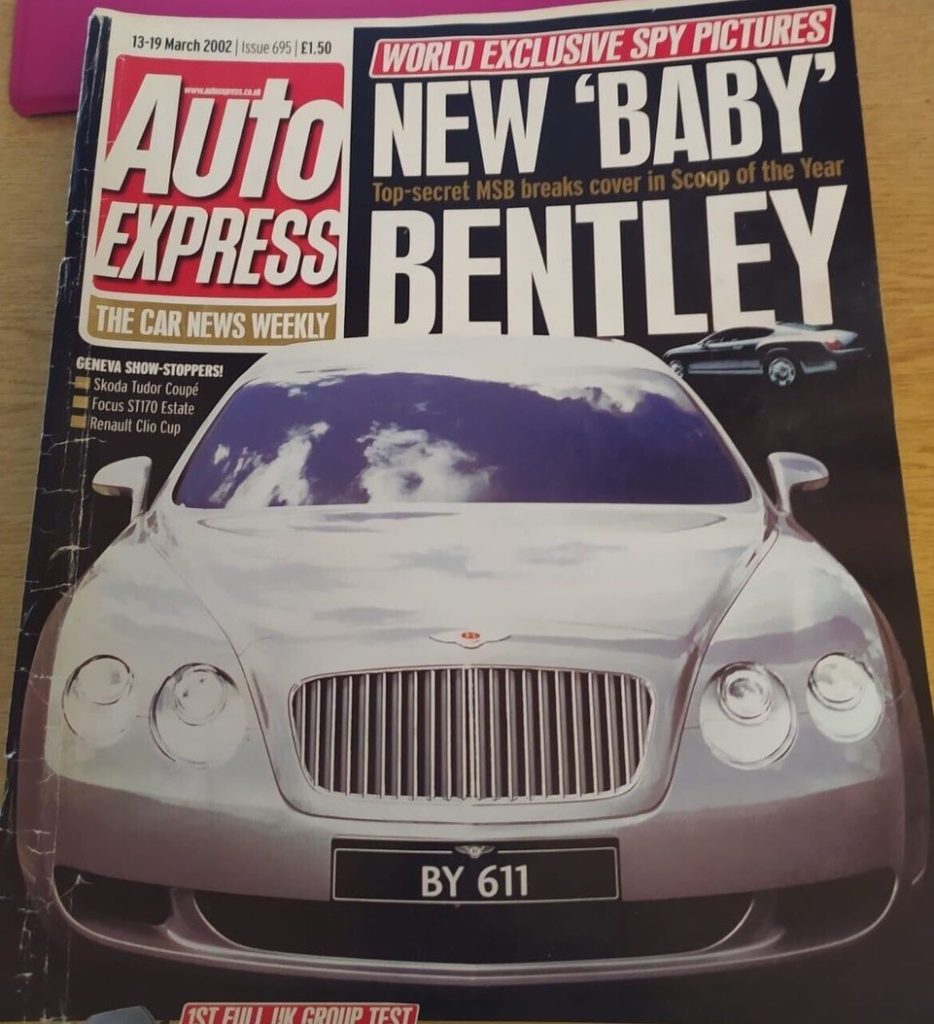

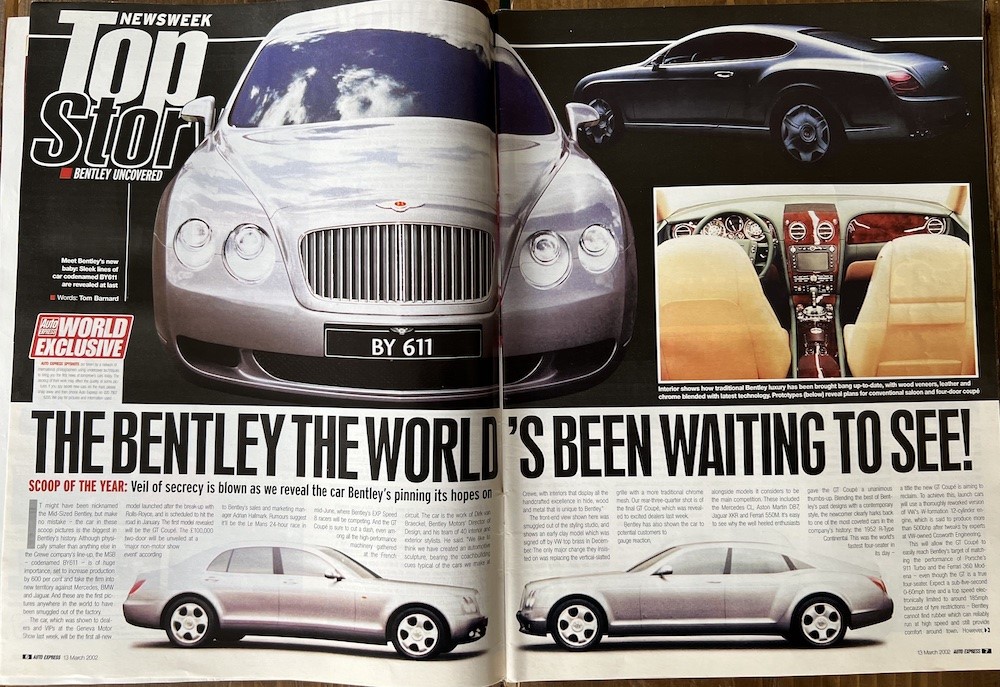

Workers at photo studios picked up discarded prints of the original Ford Focus and Toyota Corolla and, sensing opportunity, sold them to the weekly magazine. Photos of the radical Discovery 3 were taken in a supplier’s workshop by a disgruntled employee, with the fabric disguise panels carefully unzipped to show the unseen features. Others leaked brochure shots of new models they’d found in a printer’s bin, some took photographs of scale models inside toy factories. But one of Auto Express’ biggest scoops came from a Bentley employee in March 2002.

Strangers in car parks and floppy discs

A source called the news desk and offered pictures of the new Continental GT and Flying Spur, which was still 10 months away from an official reveal. He had several shots, he said, along with a lot of information. He was nervous about sending them in the post so insisted on a meeting – and wanted several thousand pounds… in cash.

It was my job to broker a deal, and I headed out to find a man wearing a disguise in the corner of a service station car park. He handed me a floppy disc, which he insisted I copy onto my computer so there was no chance of ‘his fingerprints being found’.

I could understand his paranoia. On the disc were photos from inside the styling studio of the Bentley Continental GT coupé, the Flying Spur saloon and just visible in reflections and cropped shots was a Bentley-badged 4×4 based on the VW Toureg. This was 13 years before the Bentayga appeared, and the project was killed off by CEO Franz-Josef Paefgen, who famously hated SUVs.

After two weeks of stories showing the GT and Spur, Bentley was understandably upset and threatened to prosecute Auto Express for industrial espionage. We told them the SUV was planned for the next week’s new pages; as a compromise, we promised not to publish the pictures of the 4×4 and the lawyers went away.

We didn’t always get it right though. A French photo agency sent grainy pictures of an MPV-shaped car in a styling studio along with a story of how Renault was developing a coupé version of its Espace. This seemed clearly ridiculous, so we ignored it. The Avantime appeared a year later.

While the Auto Express office was constantly being offered scoops from the network of professional photographers and their agents, occasionally a member of the public would strike gold.

In May 2005, a dog walker taking their usual route was annoyed to find a marquee had been erected across the path. He claimed his dog ran under the canvas and he followed to retrieve it, and the dog was standing next to the next Ford Focus, completely undisguised and parked next to a Volkswagen Golf and Vauxhall Astra. It was a top-secret customer research clinic, but no one was around so he grabbed some pictures on a disposable camera and returned to his walk. This was four months before the Focus was due to be revealed at the Paris Motor Show.

Another reader had a lucrative sideline to his job at an airport, selling pictures he’d taken of custom-built cars being loaded into cargo planes on their way to the Sultan of Brunai.

This kind of ‘real’ spyshot is rare now, except when the manufacturers use them as a way of drumming up publicity for a future model. Some merely release pictures which look like they have been taken by spies, knowing the media will publish them. Rolls-Royce and Land Rover went one stage further, putting QR codes on the camouflage wrapping so people could sign up for more information.

But technology was changing the spyshot forever. Priddy says: “By the early 2000s, phones with built-in cameras were becoming very popular and although the quality wasn’t up to par, many magazines and websites in the States were urging readers to submit their ‘spy photos’ as they’d rather use reader photos for free, than pay the pros.

“The magazine business was quickly changing, and fewer print publications were using spy photos. I got paid well for images used on the internet, but I got tired of chasing [third-party] web publications who used my images without paying. The fun and excitement were rapidly going away.”

Priddy made the decision to make the summer of 2013 her last in Death Valley and hasn’t returned since. She now photographs classics and organises tours of Cuba, with an emphasis on the local car culture. As for Hans Lehmann, he reportedly gave up the game in 2008, handing on the batton to younger associates who kept a hand in the game for another decade or so.

Inside jobs

Perhaps one of the most audacious scoops came during Mills’ time at Auto Express. It was orchestrated by a pair of Frenchmen – ‘Bruno’ and ‘Jean-Michel’ – who became a thorn in the side of the French car makers. “The guys had contacts everywhere, people on the take who’d tip them off or provide access or even take pictures inside a manufacturer’s facility. But the wildest scoop was of the third generation Renault Espace. Bruno and Jean-Michel paid off a security guard to pre-record 30 minutes of footage of the factory floor and then have that footage played one night – in case anyone else looked at the security monitors – while they were let into the building and spent 30 minutes photographing the hell out of the new Espace. After that, the French car makers employed a private security firm to hunt them down and, effectively, warn them off.”

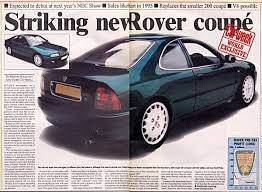

Another nail in the coffin for the traditional spy shot though was the advances in computer images, which allowed editors to create realistic-looking pictures at a fraction of the cost. Hilton Holloway was involved in the creation of the first ever computer generated ‘scoop’. He says: “We used to have some great traditional artists who would do a great job of drawing future models based on inside information. But the readers didn’t like them as much as ‘real’ pictures. On Carweek we persuaded a Ford designer to use the company’s new computer rendering machine to produce a picture of a coupé version of the Rover 600. We got a great scoop, but unfortunately Rover was very upset as they’d promised Honda that they wouldn’t do other 600 body styles as part of the supply contract. They did some detective work and realised the only place with a CGI tool capable of making the image was Ford. It was tracked back to our man, and he got fired.”

These days it is possible to create better quality images than those original Rover shots on a smartphone, and many CGI artists will fire up Photoshop as a hobby. This makes it a far cry from the five-figure sums which the likes of Lehmann and his rivals used to ask for a world-exclusive.

“A good CGI story still sells magazines though,” said Auto Express’ Steve Fowler. “But to be credible, the information has to be genuine to back up the image. You still need to use proper journalism to gather the facts and use a combination of existing models and hints from concept cars to imagine what the new model will look like.”

It all means prices for pictures have plummeted and it’s barely worth waiting in extreme conditions to get the shot of a disguised car. The thrill of the chase, and the payoff that came with a scoop, is gone.

Priddy sums it up: “Phone cameras make everyone a ‘professional’ and there are far fewer print magazines than there were 10 years ago, and the surviving publications rarely use spy photos. And then there are the car companies that release their own ‘spy’ photos!

“The golden age of spyshots is over, but I had a great time and it paid well. I miss the excitement, but I don’t miss the long hours.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it.

Those were some of the best times in my life. I miss those days, and I even miss running to Hans Lehmann. Thanks for sharing a part of our story.

b.

Fascinating stuff. I grew up on car mags & spy photos and this was a great read.

Remember a morning drive from Ford to Winchcombe on a family holiday in 1993 and seeing a strange looking Range Rover parked up with a couple of guys having a coffee. They were from Gaydon on a test run of a Japanese spec ‘new’ RR a few months away from release. They were perfectly friendly although I wasn’t allowed to look inside the car…

I remember the covers of magazine s with latest spyshot on the front cover. I also remember as a 15 year old spotting a cortina with strange bigger back lights in a compound behind Gordon Ford s garage Wigan. While I was looking a representative of the company came out glared at me and drove it indoors . It was a very early Cortina 80 or MK5 but 3 months before its official launch!

Audi still use the country roads around Malaga and still use the same black and white ‘camouflage’!

As the PR person for low volume manufacturers, I would call my news contacts on the mags and describe the test route and timing for a day the following week and where a good layby near a dramatic corner could be found. Always good to get some excitement in the market and take some deposits before launch.

I remember these well from the days of AutoWeek. If you saw a Brenda Priddy or Hidden Image tag line it was respected.

I did durability testing contracted to an engineering company in Arizona in the late 1990s. The car looked stock except for the legally required sticker based on the fuel type. Twenty-five years later and I still don’t talk about the specifics. Driving jobs were always the jobs I actually enjoyed!

Back around 1989, I was part of the SCCA safety crew at Willow Springs track. One of the other safety crew members was known for getting many spy photos at the track. So, one Sunday that will live in infamy, the unreleased ZR-1 32-valve, DOHC Corvette showed up. And at the same time, a Gulstrand Corvette prototype showed up. Both ran the track between races, but not both at the same time. And my buddy of the spy photos had absolute kittens, he didn’t have a camera with him that day!