In the 1990s, Rich Duisberg worked as a consultant in the research and development labs and quality control departments of various car manufacturers around the world. It gave him an interesting, and often amusing, perspective on how cars are made – sometimes badly. This is the final instalment; catch the others on Interiors and Bodywork.

As you may have read in previous features, bodywork and interiors can be pretty shonky when a car maker gets things wrong but, thankfully, most manufacturers nowadays know how to get it right. What surprises me is how some mainstream manufacturers still make drivetrains that leave much room for improvement.

It was back in the century-before-the-last-one that Mr Benz made the first motorcar as we’d know it and yet many manufacturers still make ‘improvements’ which actually result in a backwards step in terms of reliability. The phrase ‘sealed for life’, for example, causes palpitations for the owners of many cars with an automatic gearbox. The powertrain, in this instance, will mean the engine and gearbox, although with the rise in popularity of EVs we should also include batteries and motors, too. Since Gustave Trouvé’s first electric car of 1881, there has been much twaddle spoken about range and reliability, although be thankful that his Ornithopter did not reach mass production – it was a flying machine with wings ‘flapped’ by means of firing shotgun cartridges. You can insert your own Tesla-related punchline here.

Engines

Let’s start with the engine – a complex mechanism designed to turn fuel into oomph. Factors which affect reliability can be broken down into design, construction and operation. The design of the internal combustion engine has not changed significantly since Nicolaus Otto worked out how to suck-squeeze-bang-blow in 1861. Improvements have been incremental, with improved compression, timing and fueling happing over time. He was a clever chap, Otto, and I have no doubt he’d know what he was looking at with the cam covers off most modern four cylinder blocks. But there have been some rotten ideas that have reached production in the name of progress.

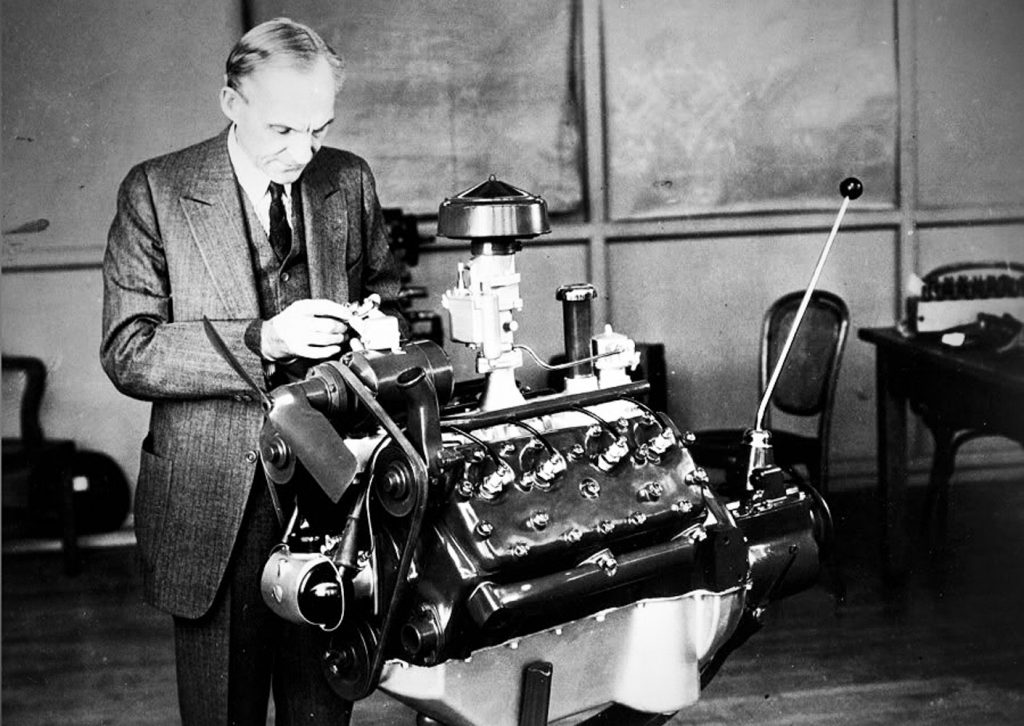

Ford revolutionised the mass production of cars, but its first V8 was not without trouble. The V8 had been invented by French company Antoinette in 1908, but Ford’s 1932 version of this configuration had cooling problems. The exhaust ports passed through the cylinder banks to reach the exhaust manifold, so the block would overheat if the large cooling system was neglected, and eventually crack. The casting method left a rough finish, which did nothing to help heat dissipation, and a lack of consistency in the casting process meant that some engine blocks left the factory with very thin walls. Water pumps were primitive and could not keep up with the heat generated. But Ford slowly improved the design and Ford’s flathead V8 went on to win awards and become a hot-rodder’s favourite. Oh, and in 1934, a certain Clyde Barrow, of Bonnie and Clyde fame, wrote to Ford to sing its praises. It was in production (in truck applications in Germany) until 1973.

As the V8 became a staple powerplant for the American masses, concerns about fuel consumption steered Cadillac towards the first cylinder deactivation system, so their L62 of 1982 could run on eight, six or just four of its eight cylinders. On the dashboard an ‘MPG Sentinel’ gadget indicated how many cylinders were in operation. The solenoids and electronics were wholly unreliable, and this great idea was wasted as dealers, fed up with the potential trouble, would pull the plug on the electronics before cars left the showroom to leave cars safely stuck in 8 cylinder mode. The HT4100 that followed was scarcely better, chewing its gaskets and having a weak, aluminium block. And, closer to (my) home, no ‘how not to build a car’ story would be complete without a visit to Rover, would it?

I am something of a motoring masochist (see here for the story of my 1972 Fiat, for example) and when I decided I was going to buy a Lotus Elise, I sought out one powered by the engine with an iffy reputation – Rover’s four-cylinder, 16-valve, K-Series. My logic was that it powered the original design, was light, revvy and frugal. It seemed well-matched to the car that carried it in the back. Well, with less than 20k on the clock and having been fastidiously maintained, it did what they all do – ate its headgasket. A mixture of poor materials (plastic dowels – really?!), poor assembly (slipped steel liners in that aluminium block) and poor design (thermostat contributing to thermal shock) meant a chunky bill to get the engine working as it should. But a sorted K-Series is well worth the inevitable bother, and a revised design lived on in the Chinese-built Roewe cars for many years to come.

Rover’s manufacturing shortcomings are well catalogued but they had some great innovations. The K Series is popular as it’s light. This comes from having a small cooling system, and from utilising a very thin cast engine block. When casting an engine, think of pouring jelly into a mould; hot liquid poured from the top. This technique is prone to ‘inclusions’ – tiny, unwanted fragments that get into the liquid and cause imperfections in the block. Think of a fly landing in your jelly. So engine blocks are usually over-engineered, using more material than is necessary, just in case. The K-Series used a revolutionary technique where the molten metal was pumped in from beneath, removing the risk of airborne inclusions, and allowing a lighter block. A 190bhp K-Series is a magnificent thing, if it’s built properly.

Of course, manufacturers compare notes. They spy on each other, learn from each other’s mistakes (sometimes) as they look for a competitive edge, money-saving solution or fuel-sipping innovation. There’s a wonderful story, which I sincerely hope is true, whereby MG got hold of an engine from a dinky Honda S600 roadster, perhaps concerned about competition with its Midget. Impressed by its revvy performance they stuck it on Rovers engine dyno to test it – and ran it from its peak power point of 8,500rpm to 10,000rpm, and still it ran fine. So they ran it to 12,000rpm and it still worked – the only thing that broke was Rover’s engine dyno.

I heard of a British manufacturer of luxury SUVs who bought a new Lamborghini Urus to secretly test the drivetrain, and an apprentice borrowed it and crashed it in less time than it took me to type this sentence. The apprentice learned a valuable lesson, but nobody learned much about design secrets.

Gearboxes

Enough iffy engine anecdotes, let’s talk of modern gearboxes. Aston Martin probably thought it was onto a good thing when it decided to launch its flagship Vanquish, in 2001, with an automated manual gearbox. But as is often the case with a technology in its infancy, you could smell when a Vanquish was parked near you in a car park, because its electro-hyraulically operated clutch was prone to wilting under pressure – you know, tricky stuff such as making a three-point turn. As Jeremy Clarkson once put it, ‘Yes, it was very fast, but only in theory. In practice it went from 0 to 6000rpm in one clutch.’

VW’s DSG ‘box (Direkt-Schalt Getriebe – direct shift gears) suffered from poor mechatronics in early production. Causes of failure included poor/dirty oil, much like Volvo’s Aisin Warner autobox used in the early 2000s, and Mercedes-Benz also suffered with poor-performing autoboxes due to ‘sealed for life’ nonsense and using lubricants which broke down over time. It’s incredible to think that such a fundamental issue as lubricant maintenance (or lack of) can still kill relatively modern cars. There’s a deep dive into some of the worst automatic transmissions ever made online, here.

Enzo Ferrari apparently once said “I don’t sell cars; I sell engines. The cars I throw in for free since something has to hold the engines in.” It’s a good assumption that if the drivetrain is good, the car is good. I’m not arguing with Enzo. He knew how to build a car.

I am sure that you will have your own horror stories to share, based on personal experience. So don’t be shy, remember we’re all here to listen, and tell us about the engineering maladies that have afflicted the cars you’ve owned over the years. One thing’s for certain when it comes to owning cars with problems, you’re not alone.

Read more

How not to build a car, Part 1: Bodywork

The Parts Bin: Shared parts for classic cars

A few things to know before stealing my 914

M32 gearbox in a mid 2000’s Z19DTH 1.9 16v CDTi Astra. Assembled with bearings made out of chocolate, it would seem.