When artist-designer Liam Hopkins was 5-years-old, he fed the family VHS recorder a slice of toast. It wasn’t to its taste. “I thought it was a little person, but it f****d it up,” says the Mancunian, with a twangy, salt-of-the-earth accent. “I remember me mam getting someone out to fix it and it getting taken apart. I was like, wow, it’s another world inside this thing.” That wonder, Liam says, triggered an obsession with dismantling things to see how they’re made, as well as an instinct to repair rather than buy new. “I was fascinated by the nuts and bolts of stuff, how one thing is connected to another.” The challenge of putting them back together was part of the intrigue too. Clapped-out televisions, kettles, and radios were never consigned to the bin.

“In the early years we’re all taught to mess about, and then as we grow older people become serious and forget what you can learn through play,” says Liam, whose favourite childhood toys were Meccano sets and Lego kits. His formal education comprises a National Diploma and Bachelor of Arts in 3D design. “The first thing I made that I was really proud of was a little cardboard dinosaur” he recalls. “That ended up going in the local library, but when it came back home me mam’s dog chewed it up.” Liam pauses to contemplate his relationship with said pet: “We never really got on.”

He was, however, fond of cardboard boxes. “Kids love cardboard boxes. I made cars and all sorts out of them. I’ve always been excited by bringing mundane materials that we use on a daily basis to another dimension.” That’s why his catalogue of work features a series of vehicles that have been reimagined using items that normally would have been binned. Including a replica race car made entirely of discarded electronic devices [e-waste], they are, he says, a visual representation of society’s throwaway culture.

“When you turn waste into something else, it becomes a vehicle that can make people think. I’ve always loved trying to give old things a new life,” says Liam, who bought a worn-out Mini for 50 quid when he was 15. “I think that’s why I like classic cars.” To fund its rejuvenation, he restored Vespas and Lambrettas for a local scooter shop; it was pristine by the time he passed his driving test at 17. “I love getting hold of things that the majority of people look at and think ‘f*****g hell, that just needs putting in the scrap yard’. I look past that.” At times, Liam’s language is as lively as his curly hair, but it’s expressive rather than combative, and more often than not serves to emphasise the passion he has for promoting a more sustainable way of living. “I refuse to work with a lot of brands, because they’re not doing things for the right reasons. It’s bullt greenwashing.”

Eager to let his art speak louder than his words, Liam’s talking point pieces have captured the attention of global and political audiences. In 2021, he used 100kg of single-use plastic to engineer a 1:1 scale replica of a Gen2 Formula E single-seater to highlight the problem of plastic pollution – approximately 11 million metric tons enter the ocean every year. Making its debut at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, Liam’s ‘Recover-E’ reproduction “was literally the centre stage piece,” he says. “All those world leaders around it, even royalty,” he continues, sounding somewhat dumbfounded. “I’m really happy that I did it, I kind of felt really proud of what I’d accomplished, but, you know, it’s a material that’s used by millions of people throughout the world every minute, so everyone who sees it can connect to it on some level.”

A collaborative project with Kids Against Plastic – a campaign group founded by children – and the British Formula E racing team, Envision Racing, the vehicle took approximately 700 hours to complete. The shell was formed from plastic sheeting Liam salvaged from a building site, and the car’s wrap comprised a colour-graded collage of single-use plastic, including flattened fizzy pop bottles, crisp packets, and sweet wrappers, which were heat shrunk and bonded onto it with a heat gun and contact adhesive glue. It was an initially messy job. “With gloves on, my fingers became glued together on several occasions, but after some tests it did get cleaner.”

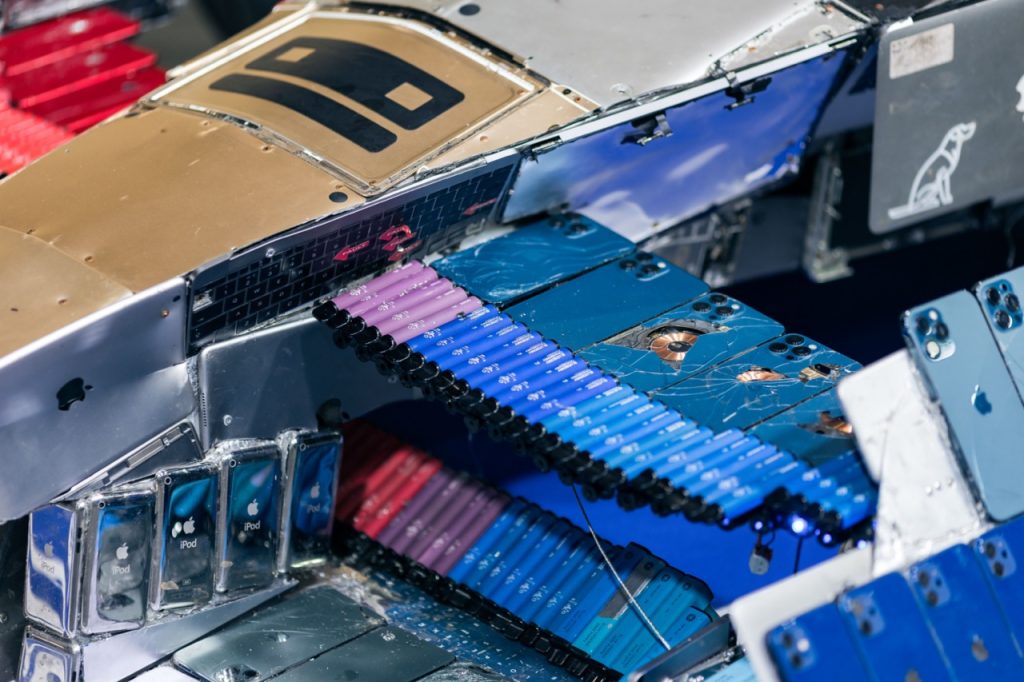

A 1:1 scale Gen3 Formula E, meticulously assembled using tens of thousands of pieces of e-waste – vapes, microchips, MP3 players, laptops, tablets, plugs, batteries, and wire – came next. “The vehicle is a symbol, it shows people that if you can’t fix something, you can repurpose it.” Identifying the obsolete gadgets that have been bonded, riveted, and backed with double-sided BHB tape in order to secure them onto the car’s aluminium body is both entertaining and enlightening. Spoiler alert, the halo was fashioned from Nintendo Wii controllers, a Sony VR headset and an electric fly swatter. The brake light is a pricing gun, and the antenna is a vintage radio. Its configuration required “a huge amount of experimentation and moving things about; if I recall correctly, I changed the overall layout and composition about eight times! I really wanted to capture the story of it revealing layers of electronics as if it’s driven at speed and losing the layers.” The overall appearance of the piece is as though it were disintegrating.

In contrast to its plastic predecessor, Liam’s e-waste reinterpretation was fully operational. “It’s not going to compete in a race, but that’s not what it’s about,” says Liam. Although the modified powertrain, taken from a beach buggy, is capable of around 50mph, Liam set the steel-chassis car’s limiter to a genteel 15mph. The real deal can hit upwards of 200mph.

Last year, the UK generated the second largest amount of e-waste as a country, and although that abundance is problematic – according to the UN, around 53.6 million metric tons of e-waste are produced every year worldwide – it means that “anyone can have a go at some hands-on making,” enthuses Liam. “It’s about getting kids to realise that there is so much you can do with these things, whether it’s a delivery box, toilet roll, record sleeve, or an iPhone. The future generation is where the hope is.”

To plan a new design, Liam will build a mock-up using drawing-board sketches, which he then turns into a three-dimension digital model using a computer-aided design (CAD) programme. This digitalisation enables him to rotate the model and view it from all angles. “I’ll work out the process of actually making it from that.” Achieving a “healthy balance” of hand crafted and machine-made elements, “purely because I love combining the two”, he upholds an old-school eye and tape-measure approach.

The engine room of Liam’s creativity is a studio that occupies a former hat factory five miles from Manchester City Centre. Founded under the name Lazerian in 2006, it is loosely divided into three areas. “You’ve got the metal shop, the wood shop, and the clean bit where the paper stuff is done,” Liam says.

Instrumental to his artistic endeavours, there’s a Bridgeport milling machine, an English wheel, a manual lathe, and a Pullmax metal working machine, alongside welders, hand tools, and saws. There’s also a computer-controlled plasma cutter and a CNC router that can etch a design into the face of a piece of wood.

The mechanical pièce de résistance is a robot Liam sourced from a Jaguar Land Rover factory. In its previous incarnation, it cut the sunroof hole out of roof liners, but on Liam’s non-industrial production line, it’s a gigantic 3D printer. “I converted it and now it never does the same thing twice.” As it builds up layers of plastic or ceramic, it’s mesmerising to watch – no wonder his blue eyes twinkle in its presence – but mention Liam’s 1950 Citroën HY van and he’ll rhapsodise about that, too. “It came from this guy who was the caretaker for Le Mans. I turned it into a mobile studio.” Fitted with an Audi A4 engine and kitted out with low- and hi-tech tools, it’s a charming “mini operations” unit.

When conversation turns to cardboard, Liam warns he’s going to nerd out. “It’s a beautiful material but people don’t value it because they’re so used to throwing it away. Look at a Picasso painting, the canvas and paint probably only cost about 50 quid, but the value is not so much in the material, it’s what’s done with it. Do you know what I mean? It also weathers well.” Given the opportunity to age, he explains, cardboard will absorb the natural oils left behind by human touch and adopt a leather-like aesthetic. The biggest challenge, he says, is understanding it as a workable medium.

A standard sheet of corrugated cardboard is made from three separate components; a layer of triangulated or “fluted” material in the centre, placed between two layers of paper. The grade assigned to a sheet will indicate how thick it is, which dictates its usability. Thicker grades are sturdier, but have a tendency to crease along the flute which makes them incompatible for sculpting curves. The most supple, says Liam, is a B flute grade, which is around 1.5–2mm thick. The majority of the cardboard he uses comes from a nearby mill that shreds, pulps, rolls, and dries old cardboard into new stock.

In 2018, Liam spent 10 weeks constructing a full-scale recycled cardboard replica of the Škoda Karoq. “It was quite difficult to recreate the smaller swathe-lines,” he says. Faithful in appearance only, the approximate 100kg curb weight was more than 12 times lighter than that of the actual car. Its spec had been reimagined using a list of must-haves chosen by a thousand under-11s. Guided by the children’s imagination, the cardboard Karoq’s 588-litre boot became a ball pit and the engine bay a secret den, accessed through a hatch that was hidden in the passenger footwell. Mini motorists also petitioned for a slide, on-board WiFi, a disco ball, and a projector so that they could watch movies on the interior roof.

The last time Liam saw the Škoda was at a secretive Volkswagen Group storage facility, parked in the company of iconic concept cars. “I was like, woah. I remember looking at some of them [cars] in magazines so it was cool to see my car alongside them.” For Liam, who dabbled with the idea of a career in automotive design, it was a full-circle moment. “But what I’m doing is probably more fun.”

There is, he promises, much more to come. “I never set out to make loads of money. I did it to be happy, and because of that I’ll never stop. I’ll never be sat down twiddling me thumbs.”