Author: John-Joe Vollans

Photography: Honda

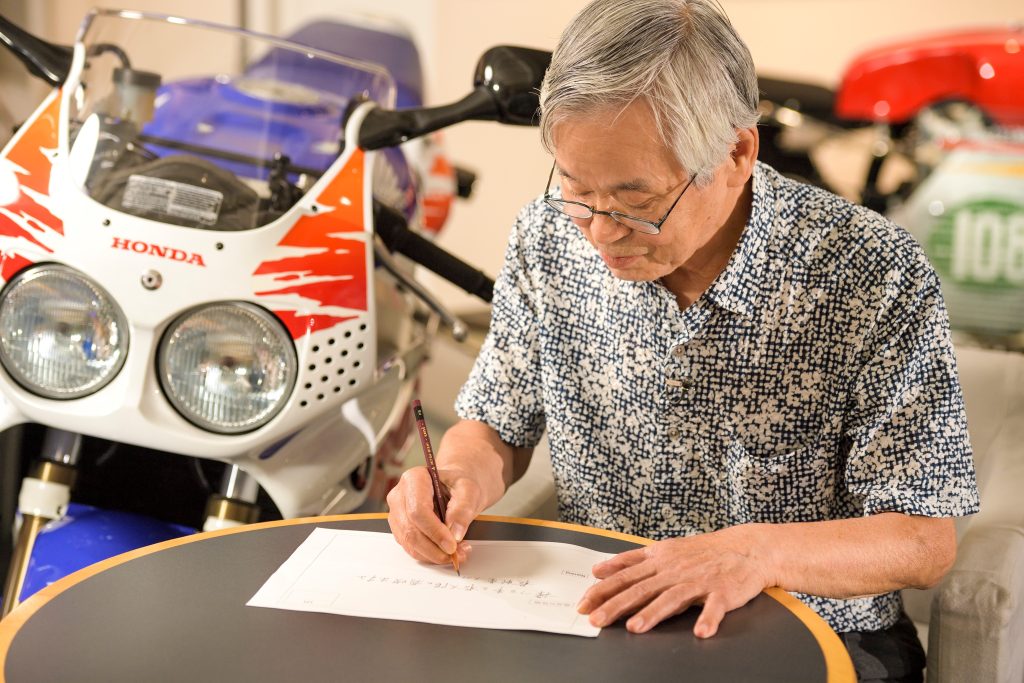

“A sport bike should be controlled freely as to the rider’s wish.” That’s according to the father of the FireBlade, former career Honda motorcycle engineer Tadao Baba. Baba-san, a real rider, was obsessed with lightweight and nimble bikes and felt much of that had been diluted down in sports bikes of the late-1980s.

Despite their products being ferociously fast, bike makers were increasingly obsessed with chasing ever higher top speeds. Performance bikes of the era were designed accordingly, able to accommodate the larger engines needed to go chasing the double ton. Frames were widened and extended and, as a result, everything got heavier. These longer, beefy bikes might have been stable at high speed, but lost a lot of ability in the bends, something Baba-san wasn’t happy about. “All the big monsters from the time were not good enough to be called a sports bike.”

The first FireBlade – named based on a loose translation of the Japanese word for lightning – was based upon a 750cc machine. Honda’s new road racer was primarily developed to decimate its own RVF750 – and, by extension, the rest of its mid-size 750cc contemporaries. More marketing minded Honda staff of the era, however, suggested that it probably wasn’t a good idea to directly compete with your own bikes. That left a neat gap for the FireBlade to sit between the 750cc and 1000cc classes. Early prototypes even ran a 750cc engine, but Baba wanted to endow the CBR750RR (as it was known internally) with the performance needed to go chasing the aforementioned straight-line heroes.

Rather than setting out from the off to effectively create the all-new 900cc class, the engineering team, lead by Baba-san, set about simply trying to make the best road racing bike it could. Having nailed the new Blade’s nimble chassis, the RVF750’s water-cooled inline four-cylinder engine was stroked from 749.2cc to 893cc. This tiny boost in capacity resulted in just three extra brake horsepower – endowing the 185kg (dry) CBR900RR with 122bhp – yet it was still enough for this featherweight machine to more than match heavier bikes out of the bends, and utterly run rings around them.

Upon its launch, in the spring of 1992, it wasn’t immediately obvious – at least to some – that this £7390 sports bike was poised to level the performance motorcycle landscape. The chassis was of a fairly conventional twin-spar aluminium design, with its front fork and 16-inch front wheel deemed thoroughly conventional even, perhaps, a little dated.

The FireBlade’s real talents, however, weren’t obvious until you got on it and threw it down a twisty road. The bike’s ludicrously low weight – 20kg (44lbs) lighter than its closest contemporary rival (Yamaha FZR1000) – meant its mass was easy to control, enhanced further by keeping what little weight there was centralised. This made the original FireBlade a breeze to handle, flattering the rider. The engine’s lengthened stroke also gave it fearsome mid-range firepower, although its on-paper statistics still weren’t deemed dazzling. It was the bike’s real world performance that blew the competition into the weeds.

The first FireBlade was so good it effectively created a new market sector, one that placed handling and rider engagement above all else. Its automotive equivalent on four wheels was probably the Lotus Elise, which equally went on to set the four-wheeled world alight, four years later. Also, in common with that Lotus lightweight, the FireBlade inspired a host of imitators, but Honda didn’t rest on its laurels…

A follow-up FireBlade arrived in 1994 with most minor moans levelled at the original having been addressed. There was now adjustable compression damping for the front fork, greatly improving (but not curing) its slightly lively front end. Weight-loss chasing components like a magnesium cylinder head cover and revised front cowling, together with improved transmission engagement, further refined the bike’s feel, but its most obvious update was its new ‘fox eye’ multi-reflector headlight.

The FireBlade kept being refined by Baba-san and his team throughout the late 1990s with a big update in performance for the RR-W/X of 1998. Displacement was hiked to 918.5cc with 128bhp now on tap. More suspension and ergonomic tweaks kept the FireBlade in keeping with the competition but its lead in the sector had finally been reined in.

For the new millennium, the FireBlade had to be updated significantly to stay competitive. The front fork and wheel were finally redesigned to incorporate a modern (for the time) inverted 17-inch affair, but the engine received an even more dramatic overhaul.

Fuel-injection replaced carburation for the first time, with the new 929cc motor developing around 150bhp. One final model, helmed by the father of the FireBlade, came two years later with the 954cc Blade seeing a further hike in capacity and updated chassis and suspension before Baba-san took his bow.

The next noughties FireBlade had to jump up a class to the full-fat 1000cc segment to stay competitive. The all-new 2004 CBR1000RR took its inspiration from Honda’s hugely successful RCV211V MotoGP machine. Its 998cc motor now made an extremely healthy 170bhp, with clever tech like Honda’s electronic steering damping, and later lighter camshafts, allowing for even greater control and low-down torque delivery.

By 2008, Kyoichi Yoshii was in charge of the FireBlade’s development, with the new RR-8 model his attempt to return to the model’s enormously influential simple and lightweight origins.

FireBlades since have seen the expected hikes in power and performance with traction-control and various other technologies making them successively easier to ride. Though with all that tech, we can’t help but feel that some of the purity of the old FireBlades has been lost. After all, these bikes were created to bring back the inherent joy of engaging in a 1-to-1 ratio between man (or woman) and machine, without any electronic trickery.

Progress only goes in one direction but now, at least, we have both the more daily liveable modern FireBlades and the more challenging weekend classics to savour. The best of both worlds available from one of the most influential ranges in performance bike history?