In hindsight, the original Austin-Healey seems an unlikely product for Britain’s biggest homegrown motor corporation to have built and sold. It’s the sort of car you would expect to be built by a specialist and sold in small quantities. In the 1950s, though, Britain was the world’s most prolific producer of sports cars and the ‘Big Healey’ was the epitome of a good, muscular example of the genre.

Such was its following that it continued well into the next age of motoring even as modern designs proliferated all around. Production, most of it at MG’s Abingdon plant, didn’t end until late 1967. It started, at Austin’s Longbridge factory, in 1953, the result of a deal between Donald Healey and Austin chief Leonard Lord. Healey had been building low-volume sports cars and coupés at his factory in Warwick, but designing a car for what had recently become the British Motor Corporation was a useful boost for his business.

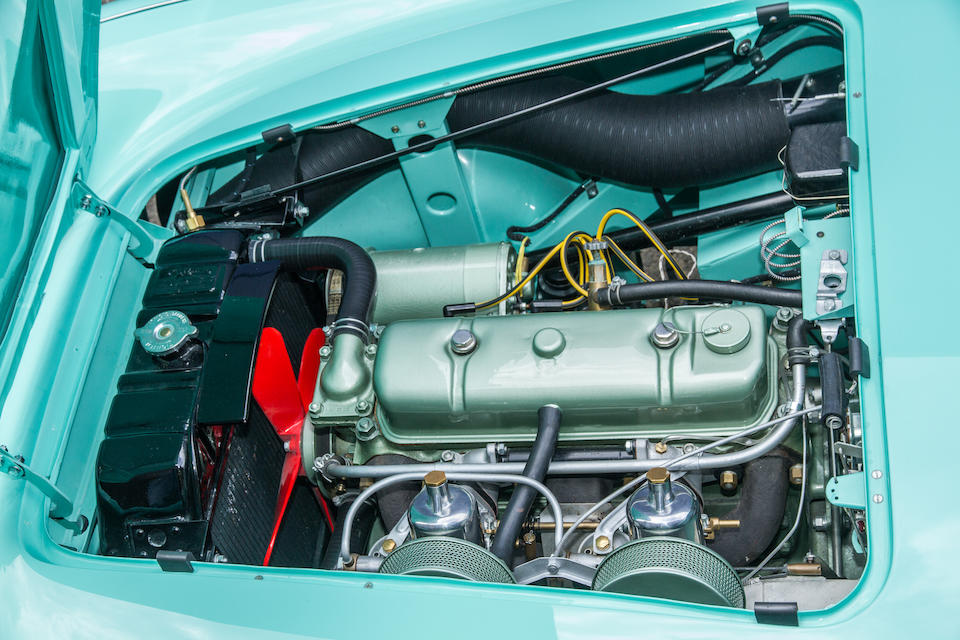

The new breed began with the Austin-Healey 100, so named for its approximate top speed. Power came from Austin’s largest four-cylinder engine, originally used in the immediately post-war Austin 16 and the company’s first overhead-valve unit. Then of 2199cc and featuring a very long stroke, it was bored out to 2660cc for the somewhat unsuccessful Austin Atlantic. Its second home in the Healey proved rather more successful, and its 90bhp offered plenty of pace by 1950s standards given that the new sports car weighed under a tonne.

By production’s end the view under the bonnet was very different: the Austin-Healey 3000, as the car had become, featured six cylinders in a 2912cc engine delivering 150bhp. Between these extremes came myriad small evolutions, which we shall now unravel in this buying guide.

That first Austin-Healey 100, internally designated BN1, has a curious gearbox arrangement. The gearbox itself is an Austin four-speeder, but first gear is blanked off (unnecessarily low) and an overdrive is added to work on second and top gears. Result: a five-speed transmission, which requires juggling of both a strange lever emerging from the left side of the tunnel and a switch to get all five in the right order. The BN1 also has a windscreen able to be laid back almost flat, to reduce wind resistance. You’ll need sunglasses or goggles if you do this, unless you fancy scraping flies from your eyes.

Under the skin is a hefty chassis to which floorpans and the bulkhead are welded to make a semi-unitary structure. Suspension is standard 1950s fare, with coil springs and wishbones at the front and a leaf-sprung live axle at the back, its location helped by a Panhard rod. Dampers are old-fashioned lever-arms, and the similarly old-fashioned worm-and-peg steering box sits ahead of the front axle line – not great in a crash, especially as the long steering column isn’t collapsible. Best not to think about that.

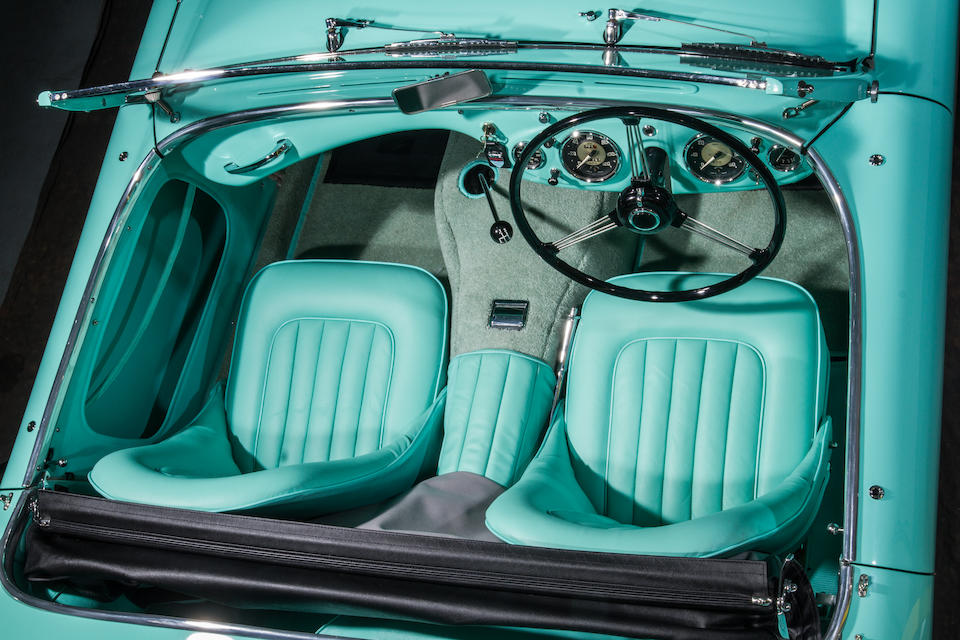

The front grille is a widened version of earlier Healey grilles, and cabin furnishings are minimal. Here is the Big Healey in its purest, most basic form. Two years on it became the BN2, with a normal four-speed gearbox (plus overdrive, usually) and an extra swage behind the rear wheel arches to delineate the colours in the newly-introduced two-tone options.

Some BN2s – 601 in all – were upgraded to 100M specification at the factory and some more were converted subsequently. The kit included larger carburettors (a pair of SU H6s instead of H4s) fed through a filterless air box, plus higher compression and a hotter camshaft, all topped by a louvred bonnet. Carrying out a similar conversion is popular today, because the extra 20bhp makes for a very fine-driving Healey.

A yet speedier evolution was the 100S, intended for racing, featuring a bumperless aluminium body with a pointed-oval grille that previewed that of later 3000s, plus disc brakes all round and a heavily-modified engine fitted with a new aluminium cylinder head. This had its porting moved to the opposite side, to allow separate instead of siamesed inlet ports and consequently much more power – 135bhp. Just 55 examples were made, five at Healey’s Warwick competitions department, 50 at Longbridge, and most went to the US.

From 1956, the mainstream four-cylinder cars would be retrospectively and unofficially known as 100-4 because a new model had replaced them: the 100-6. Into its heavily revised chassis was placed BMC’s 2639cc six-pot, first of a line later to be dubbed C-series, and that chassis also allowed fitment of tiny rear seats (BN4 model) although a two-seater (BN6) remained available. It must be said that the new engine added little in the way of pace, having a slightly smaller capacity than the outgoing four, weighing rather more and offering a lazy 102bhp. However, when production moved from Longbridge to Abingdon in late 1957, 100-6 modfications included a 15bhp power increase.

The 100-6 had a new face, too, with a pointed-oval grille spanned not vertically by straight slats but horizontally by wavy ones, an Austin design mark of the time. The bonnet now sported an air scoop, and the fold-flat windscreen had long gone. Next, in 1959, came a capacity hike to 2912cc, a power rise to 124bhp, front disc brakes and a new name: Austin-Healey 3000. Healey-watchers would note that the four-seater was coded BT7 (four-seater) and BN7 (rarer two-seater).

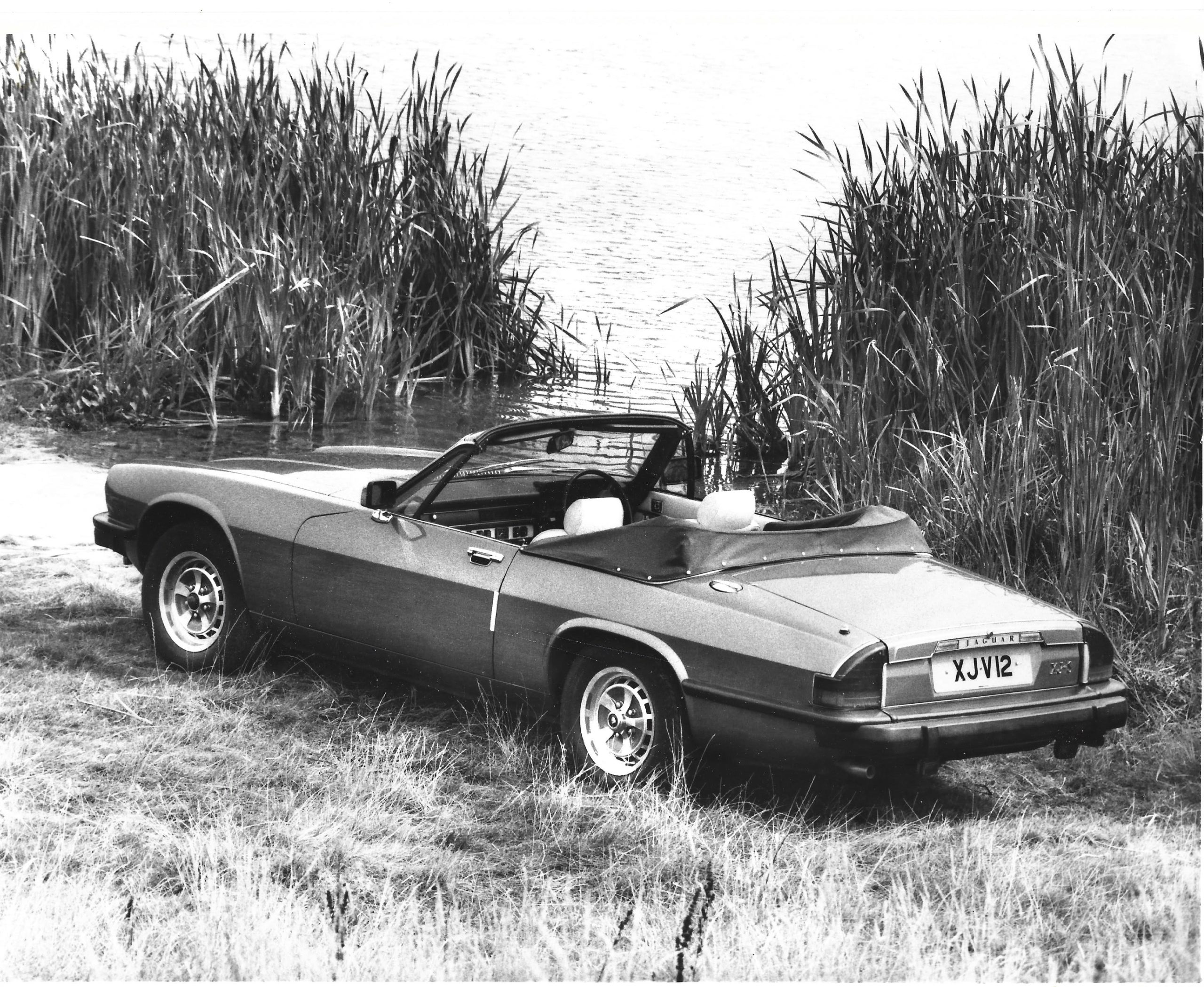

Two years later, the 3000 MkII – still BN7 and BT7 – reverted to vertical grille slats in the pointed oval, and gained a trio of SU HS4 carburettors (and an extra 8bhp) instead of the previous pair of HD6s. Some way into production a new gearbox finally allowed the lever to emerge from the middle of the tunnel, and in 1962 the MkIIA (BJ7, and two-plus-two only) arrived with, at last, wind-up windows and an easily-folded hood. It also reverted to twin carburettors, now HS6s, with a reduction in claimed output of just 1bhp, making 131.

Finally, in 1963 came the MkIII or BJ8. It had bigger twin carbs (SU HD8), 148bhp, a luxurious-looking walnut-veneered dashboard, a fold-down rear seat and, from May 1964, some chassis changes to fix, rather belatedly, the perennial Big Healey problem of minimal rear ground clearance. The chassis rails were re-shaped, radius arms replaced the Panhard rod and the exhaust system was tucked up behind the adjacent sill.

And there, in 1967, it ended, after a career festooned with rally wins (Pat Moss in the 1960 Liège-Rome-Liège being a particular highlight) and a shelved plan to make a wide-bodied, Rover V8-powered version. At one point, BMC was considering replacing the 3000 with a re-grilled, Healey-badged MGC; after all, the smaller Sprite and Midget had long been the same car. We can be thankful that sense prevailed.

What’s an Austin-Healey 100 and 3000 like to drive?

The popular view is of a growling six-cylinder bruiser, the ‘hairy-chested sports car’ that takes commitment and bravery to tame. The 100/6 and 3000 aren’t really quite like that, though. Yes, the steering is heavy at low speeds, the ride can get choppy and the exhaust note is marvellous, but these are great mile-eating sports cars with lots of torque and an untemperamental nature. Later cars with wind-up windows and a better hood are surprisingly practical, too, and the MkIII with its wood and plushness is almost cosseting – especially in final form with softer rear springs and more spring travel.

All that said, in some ways the four-cylinder cars are more fun to drive. They are lighter, less nose-heavy, the engine is still muscular at low revs and the simplicity of their cabins has its own appeal. A Healey 100M, either original (expensive and rare) or recreated (popular and recommended) is one of the sharpest, keenest, most engaging sports cars of its era and plenty quick enough to hold its own on today’s roads.

A very early Austin-Healey 100 BN1 has its own charms, too. Not only does the cranked-over gear lever offer only three forward ratios, its gate is reversed with first gear towards you and back. Drive a BN1, and you’ll never forget you’re in something unusual.

How much does a Big Healey cost?

Sellers of the ultra-rare 100S can almost name their price, probably settling on around half a million pounds. Original 100Ms can easily make £150,000, maybe more. In the world of regular production Healeys, though, good cars are rather more affordable if hardly cheap.

Hagerty’s value guide – which you can browse by clocking this link – shows us the perhaps surprising fact that the very earliest BN1s and the very last BJ8s are worth almost exactly the same, be they care-starved runners at £27,000 to £28,000 or concours perfection at £96,500. In both cases, around £50,000 will buy you an excellent car; the leap from there to true concours is an unusually large one, it seems.

Earlier 3000s are a little cheaper, with a slight premium on two-seater examples, but the value choice among Big Healeys is the 100/6 with a range from £20,300 (unloved) to £81,600 (concours) – take a look at the years and values by clicking this link to the Hagerty Price Guide. Here, about £48,000 should buy a very smart two-plus-two, fractionally more a two-seater.

What goes wrong, and what should you look for when buying a Big Healey?

By far the biggest worry is the condition of the body and chassis. Mud traps abound and factory rustproofing was non-existent. The ‘shrouds’ – the panels between each pair of front and rear wings which surround the bonnet and bootlid – are made of aluminium and there’s plenty of scope for electrolytic corrosion where they meet steel.

Obviously the wings, doors and sills all need a careful check for rust and filler, and alarm bells should ring if the swages along the body sides through wings and doors don’t line up. Inner sills, floorpans, scuttle and footwell areas – inspect them all. Also check the A- and B-pillars, the boot floor and the ‘boot boxes’ into which the rear leaf springs attach.

As for the chassis members, check the outriggers for rot and the front crossmember for damage, typically caused by jacking under it. Restorers usually fit a stiffener inside the new crossmember tube when rebuilding a chassis. The door gaps and how well the doors open and close can give a clue to the strength of the chassis. It’s worth jacking the car up at the back of the chassis and checking if the gaps are maintained under this stress. On a good, solid car they will be.

There’s nothing especially complicated or troublesome about a Healey’s mechanical parts, but on a road test you should check for easy gear selection, that the overdrive works if fitted (non-operation may just be down to a faulty solenoid, but the whole unit might need a rebuild), that the steering feels positive allowing for that fact that it’s an old-fashioned steering box, and that there are no untoward knocks or grumbles.

Usual checks for oil pressure, overheating, leaks and exhaust smoke apply. The four-cylinder engines, especially, are very old now but many have been rebuilt. Fitting a reproduction cylinder head, to the original pattern but made of aluminium, is a popular modification. The original iron head is prone to cracking, cured by fitment of modern replacements which also have hardened valve seats suitable for unleaded petrol.

Car sales, restoration services, parts and expertise are readily available from companies such as JME Healeys (operating out of the original competitions department building in Warwick), Rawles Motorsport, AH Spares and more.

Which is the right Austin-Healey for you?

The 3000s are the most numerous, the fastest and the easiest to live with on a long road trip, and for many they are the archetypal Big Healey. But the 100/6 offers a similar feel combined with the more basic appointments of the earlier cars. If you fancy the powerful hum of six cylinders combined with a sense of pioneering sports-car motoring before Austin-Healey ‘went soft’, a 100/6 could be the value choice.

Some, though – this writer among them – will revel in the surprising lightness and fleetness of the original four-cylinder cars, which also respond very well to some judicious tuning. A lightly-enhanced 100M recreation is perhaps the most enjoyable, while still reasonably affordable, Big Healey of all.

Read more

Why America is falling in love with the Austin-Healey Frogeye Sprite – again

The complete guide to £50,000 starter classics

Reassembling the clutch: Austin-Healey Sprite project car

Very comprehensive and informative article.must read for potential buyers

Where can I buy a Austin Healy Mark III, British Racing Green for under $45,000?

I am in the market for a Big Healey! I have owned two i was restoring years ago. Lost them

during A divorce but i can afford at least one mow

You have reversed the big Healey model designations in your article. The BN7 is the two seater and the BT7 is the four seater.

“Next, in 1959, came a capacity hike to 2912cc, a power rise to 124bhp, front disc brakes and a new name: Austin-Healey 3000. Healey-watchers would note that the four-seater was coded BN7 (four-seater) and BT7 (rarer two-seater).”

Good catch, Steve. Thank you. The post has been updated.