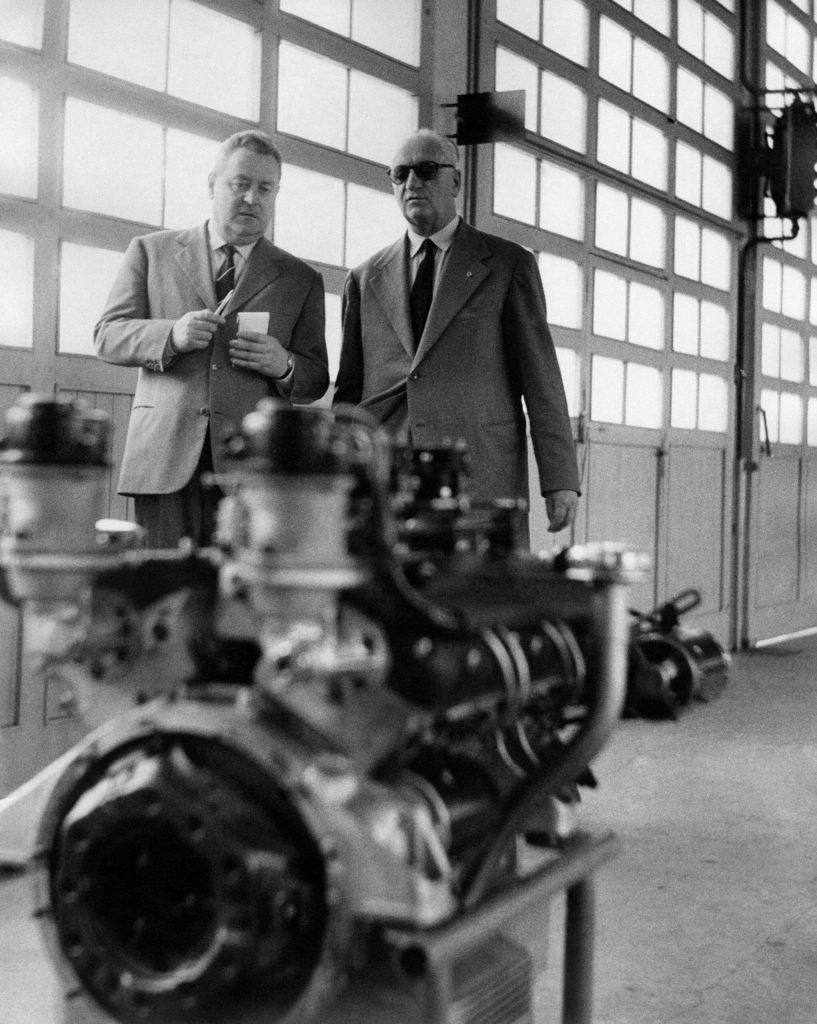

In the summer of 1945, only a few months after Allied bombers stopped punishing Italy for its WWII transgressions, Enzo Ferrari summoned his trusted colleague Gioacchino Colombo to Maranello for consultations. Though postwar racing rules had not yet been announced, Ferrari was anxious to build his own cars to compete. Anticipating a 4.5-litre displacement for naturally aspirated engines and a 1.5-litre limit for supercharged powerplants, Ferrari sought the advice of one of Italy’s foremost engine designers.

Asked how he’d construct a new 1,500cc engine, Colombo mentioned ERA’s promising six-cylinder and eights under development at Alfa Romeo and Maserati before proclaiming, “In my view, you should build a 12-cylinder!”

The usually aloof Ferrari lit up like a Roman candle. Turns out the 47-year-old racing don had admired V12s for years after hearing primo piloto Antonio Ascari rev the engine in his 1916 Packard racer and seeing WWI American military officers cruise Italy in their majestic Packard Twin Sixes. He and Colombo immediately began conceptualising the Scuderia’s first V12, the engine destined to become the Prancing Horse’s heart and soul.

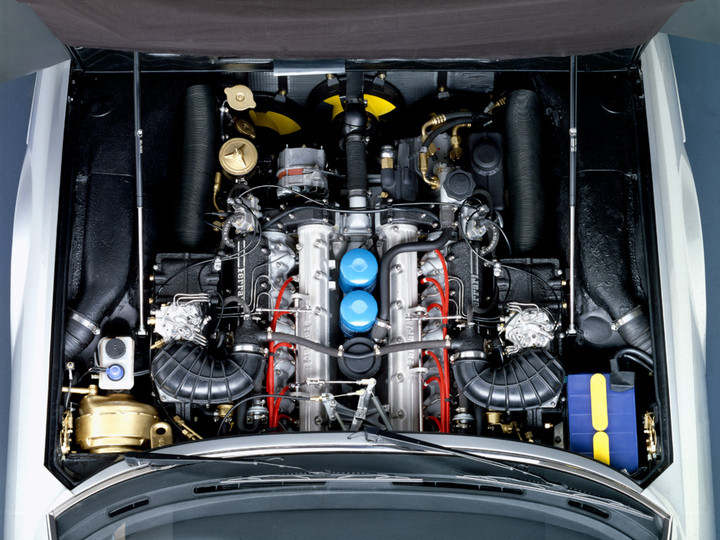

Ferrari’s timing was perfect because Colombo had been laid off by Alfa Romeo due to Italy’s postwar economic turmoil. Though the 42-year-old lacked a formal technical education, he had served a lengthy apprenticeship designing engines, including V12s, under Alfa Romeo’s brilliant Vittorio Jano. Colombo erected a drafting board in his Milan bedroom and in a few weeks completed sketches of both a new V12 and the Ferrari 125 S sports-racer it would power. His guiding light was versatility in order to serve wide-ranging racing applications and eventual road use.

Packard’s 1916–23 Twin Six, the world’s first production V12, made 88–90 horsepower from 6.9 litres. The beauty of a dozen cylinders in a V is perfect balance – freedom from the shake, rattle, and roll resulting from pistons starting and stopping at the ends of their strokes. (The same is true of an inline-six; a V12 is simply two banks of six cylinders sharing a common crankshaft. A 60-degree angle between cylinder banks yields the even firing intervals necessary for smoothness.)

Before we delve into Colombo’s V12 design features, it’s essential to understand the operational details within every four-stroke engine. First, there’s an intake stroke when one valve opens to admit air (and usually fuel) to a cylinder while the piston moves top to bottom. Next is compression, with both valves closed and the piston rising in the cylinder, squeezing the mixture. Near the top of the piston’s travel, electricity sent across the spark plug’s gap serves as the match to light the bonfire inside one cylinder. Rising combustion pressure within the cylinder drives the piston back down, spinning the crankshaft and driving the wheels through the transmission. Then comes exhaust, when the piston again reverses direction, forcing burned gases out of an open exhaust valve and into a pipe connected to the cylinder head through an exhaust manifold. Simply described, the four-stroke cycle is suck, squeeze, bang, blow.

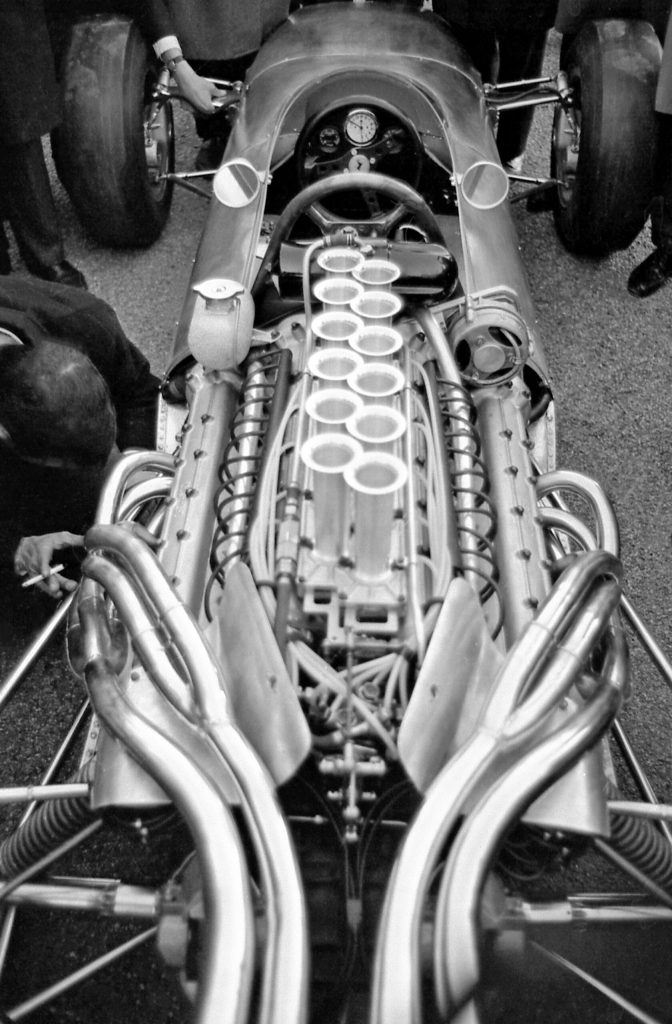

Given that each power stroke lasts the better part of 180 degrees, in a V12, there are three overlapping power strokes at any given instance to run through all the cylinders in two turns of the crankshaft. As a result, output feels more like a continuous twist than discrete pulses. A V12’s exhaust note can be whatever the designer desires, between a gentle purr and a coyote’s shriek.

V12s do have several less sanguine design issues – added friction, heavier weight, higher cost, and their overall length. It goes without saying that when value and mpg are top priorities, carmakers steer clear of V12s.

To minimise mass, Colombo chose aluminium over iron for the block and head castings. Italy had become an epicenter for bronze casting during the Renaissance back in the 14th century, specialising in statuary, equestrian monuments, cathedral doors, crucifixes, and even dishes.

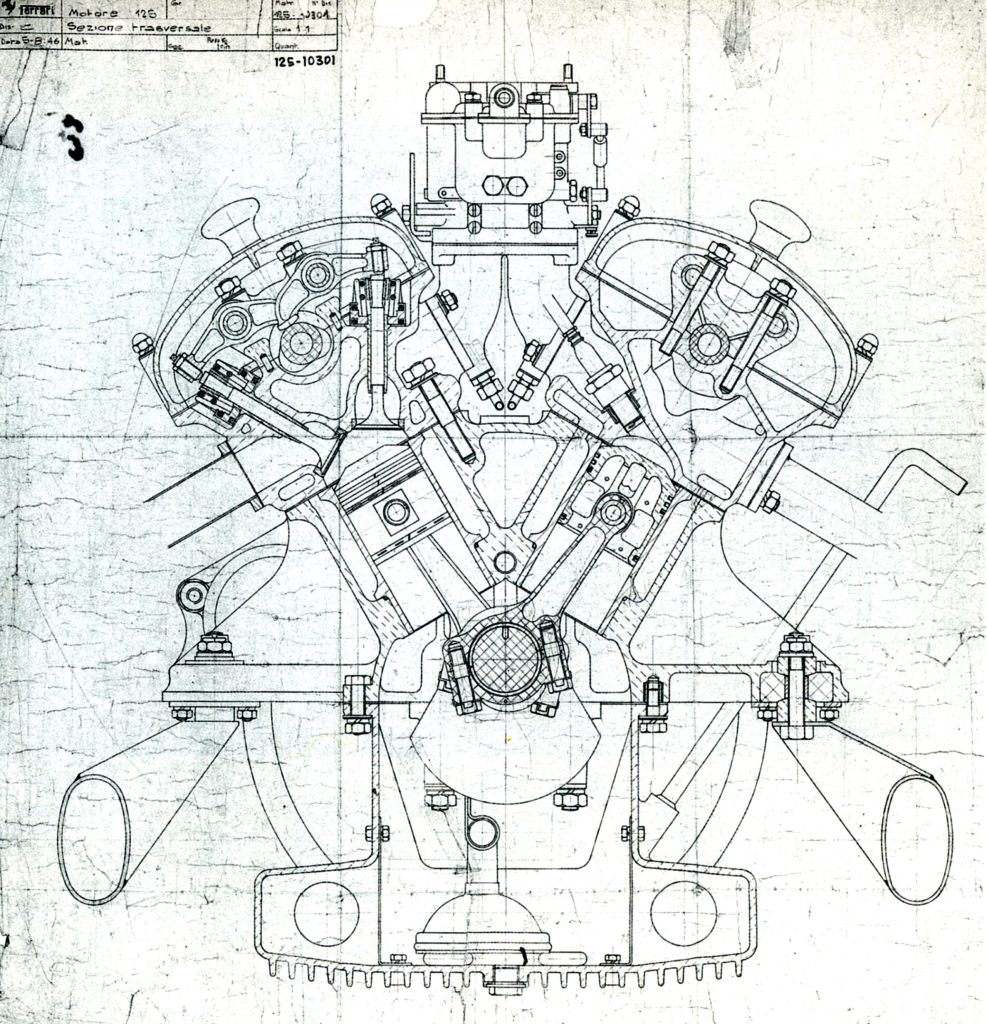

Combining a 55.0mm bore with a 52.5mm stroke yielded the target 1.5-litre (1,497-cc) piston displacement. Cast-iron cylinders wet by coolant were plugged securely into the bottom of the block with a shrink fit (achieved by heating the aluminium block to expand openings before inserting cold iron cylinders. Once the cylinders and block reach the same temperature, they’re securely locked together).

Bolts securing both the heads and the cylinders screwed into the block’s upper decks. Since the block’s side skirts ended at the crank centerline, the cast aluminium oil sump had ribs to radiate heat and to increase the engine’s overall stiffness. The crankshaft was machined from a single billet of alloy steel with seven main bearings and six throws spaced 60 degrees apart to provide even firing intervals. Connecting rods were forged steel.

One chain-driven overhead cam per bank opened two valves per cylinder through rocker arms. Locking screws touching the valve stems facilitated lash adjustment. (Lash is the small space in the valvetrain that allows each valve to seal tightly against its seat in the closed position.) The valves were splayed 60 degrees apart to straighten and streamline ports for maximum flow of air and fuel into each cylinder. A domed (aka hemispherical) combustion chamber topped each cylinder. Colombo screwed the spark plugs in from the intake side of the heads because the bore-centre areas were blocked by the single overhead camshafts.

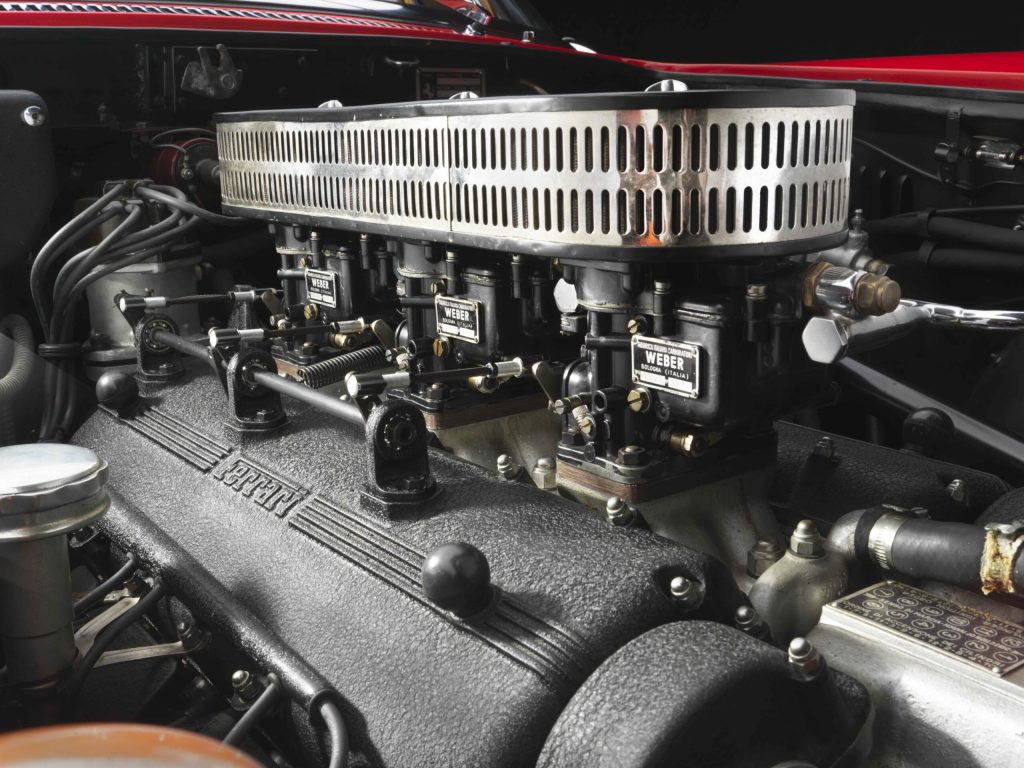

Three downdraft two-barrel Weber carburettors prepared ample amounts of fuel-and-air mixture. Twin Marelli magnetos driven off the tail end of each camshaft supplied the ignition energy. Initial output with a 7.5:1 compression ratio was 118 horsepower at 6,800 rpm.

To provide a path to more power, Colombo gave his seminal V12 three innovative features. The first was what’s known as an over-square bore/stroke ratio (a figure greater than one). The unusually short stroke diminished the pistons’ reciprocating motion, minimized the height of the block, and lowered the engine’s centre of gravity. The relatively large bore in turn allowed larger valves (see end-view illustration), a boon to volumetric efficiency (fluid flow in and out of the cylinder head). The net result of Colombo’s over-square design was a rousing 7,000 rpm available at the beginning of this V12’s life. His second fundamental inspiration was 90mm cylinder spacing to facilitate significantly larger bores and additional piston displacement with minimal changes to the overall design.

Colombo’s third special feature was the type of valve springs he incorporated. Instead of the spiral-wound coil springs that are now common practice, he used what was called a “hairpin” design (despite the fact they more closely resembled springs found in clothespins). He was inspired by air-cooled motorcycle engines, which used such a configuration for three key reasons:

The first is that the hairpin design was less susceptible to fatigue failure that, in the worst case, would destroy the engine when an out-of-control valve struck the top of a piston. Second, the hairpin design was a better means of exposing the valves to cooling air swirling over the top of the engine. Third, this design allowed shorter and lighter valve stems. Lighter valves are less susceptible to the fatigue failures common with racing cam lobes. In summary, the hairpin spring design was instrumental in helping Colombo’s V12 withstand the rigours of racing. Two such springs were fitted to each intake and exhaust valve.

A paucity of intake ports was the most notable shortcoming in Colombo’s V12. Since Ferrari hoped to add a Roots-type (twin interlocking lobes) supercharger, there were but three intake ports feeding six cylinders per bank. This arrangement made it more difficult to ram-tune naturally aspirated versions of the engine for competitive power at high rpm. (Ram tuning uses fluid-flow momentum to pack the maximum amount of air and fuel into each cylinder.)

With the ink barely dry on blueprints, Ferrari attacked the 1947 racing season with a two-seater dubbed 125 Spyder Corsa. The 125 code referred to the number of ccs per cylinder, spyder is Italian for roadster, and corsa is the boot country’s word for racing. Nine entries yielded two victories by Franco Cortese, two class wins by Tazio Nuvolari, one third, one fifth, and three DNFs. Adding a supercharger for its 125 Formula 1 single-seater yielded 230 horsepower and the Scuderia’s first grand prix victory. By October of ’47, Ferrari was ready to move up with a 1,903cc V12 dubbed 159, followed by a 1,995cc 166 for the 1948 season.

The rising costs of fielding competitive cars in road races, endurance competitions, and F1 are what moved Ferrari to offer his cars to wealthy customers bent on enjoying them on the road.

In a 1984 test of the first 1947 Ferrari 166 Spyder Corsa delivered to a private owner, Car and Driver clocked 0–60 in 13.1 seconds and estimated top speed at 121 mph. Weighing less than 680kg, this red roadster rode on skinny 15-inch Michelin X radial tyres. Respecting the vintage Ferrari’s rarity and fragility, C/D’s test driver used only 6,000 rpm, so a run to 60 in under 10 seconds is probably within the Spyder Corsa’s reach.

Bolting on a two-stage supercharger in 1949 raised output to 280 horsepower, earning Ferrari five Grand Prix wins. In spite of the Scuderia’s early successes, Ferrari demanded more; Colombo fell out of favor and returned to Alfa Romeo in 1951. His successors? First Aurelio Lampredi, a former aircraft-engine designer, then four years later Colombo’s mentor Vittorio Jano, who continued development of Ferrari’s first V12 for another decade.

Colombo’s masterpiece grew from its original 1,,498 cc to a maximum 4,943 cc in its final Ferrari 412i form. The 1957 250 Testa Rossa brought conventional coil-type valve springs, spark plugs relocated to the outer side of the heads, and one intake port per cylinder. These changes yielded 300 horsepower from 3.0 litres, enough prancing horsepower to win 10 World Sportscar races, including three Le Mans 24-hour events between 1958 and 1961. Ferrari 250 GTO sports cars that followed won the FIA’s over-2-litre championship from 1962 through 1964. In 1964, a 4.0-inch stretch of the block increased bore-centre spacing from 90mm to 94, allowing 4.0-litre and larger displacements.

Features proved on the track rapidly trickled down to Ferrari’s road cars. Dual overhead cams, still operating but two valves per cylinder, appeared on the 1967 Ferrari 275 GTB/4. The illustrious 1968 365 GTB/4 Daytona came with dry-sump lubrication. (Keeping oil well away from a frantically spinning crankshaft eliminates what’s known as “windage,” frothing of the lubricant, which saps power output.)

In 1979, carburettors went the way of the buggy whip with the introduction of Ferrari’s 400i equipped with Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection. This added power by diminishing the flow restriction that is imposed by carburetor venturis.

Ferrari’s 1985 catalog listed an amazing 75 60-degree naturally aspirated (no super- or turbocharger) V12 engines designed over the previous four decades. The venerable Colombo stallion wasn’t dispatched to the glue factory until 1989, by which time Ferrari had shifted its focus to 180-degree (flat) 12s for the 365 GT4 BB (Berlinetta Boxer) and its successors. (They’re called that because the horizontal motion of the pistons resembles boxing gloves smacked together.) Even so, these new engines inherited their pistons and connecting rods from Colombo’s outgoing design.

The V12 today

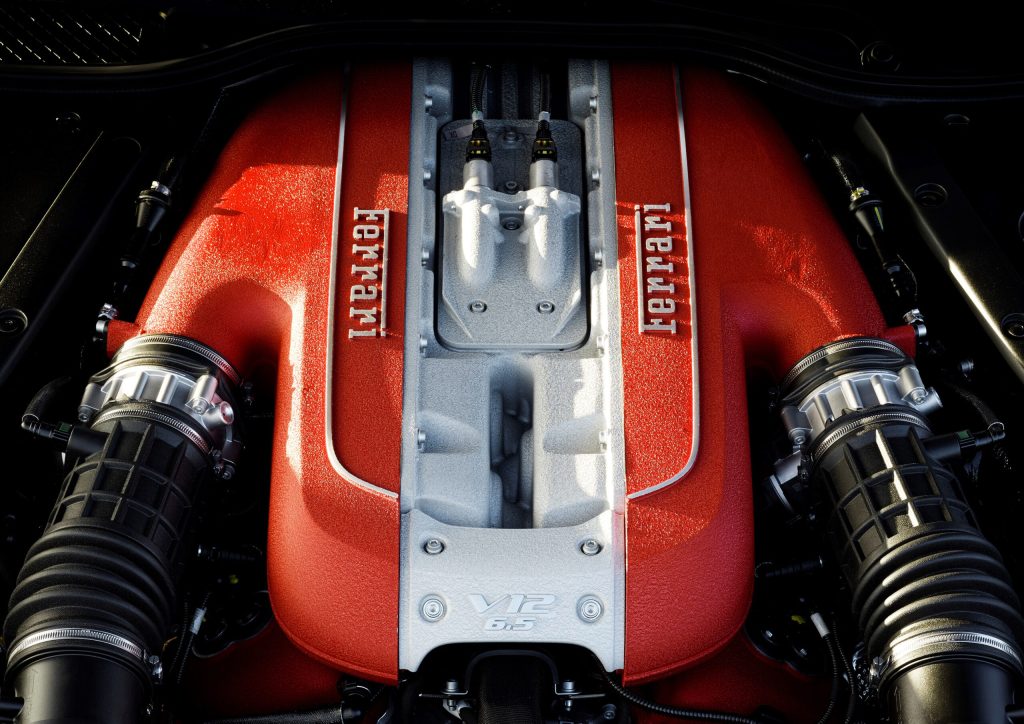

Fast forward to the March 2017 Geneva motor show. Although most makers follow new trends like a puppy locked on to a rabbit’s scent, Ferrari used this European gala to toast its 70th birthday with what it excels at building and selling: a fresh V12 to power its new aptly named 812 Superfast sports car.

The first number in the 812 code refers to this engine’s peak power (in hundreds); the next two indicate the number of cylinders. That’s 800 metric horsepower at a canvas-shredding 8,500 rpm.

What Ferrari achieved with its F140 V-12 was the most power ever packed into a production engine unaided by a turbocharger, supercharger, or electric motor. Add to that more than adequate torque: a peak 530 bft at 7,000 rpm. Those in the audience who favour the lower end of the tachometer will be happy to hear that a stout 425 lbft of twist is available at only 3,500 rpm.

In keeping with longstanding Ferrari tradition, this is a Testa Rossa engine adorned with striking red valve covers and intake plenums. Naturally the bore/stroke ratio is markedly over-square, with a 94mm bore collaborating with a 78mm stroke to yield 6,496 cc. That 78mm dimension ironically matches the longest stroke ever found in a Colombo V12.

In contrast to the Colombo V12s, the 812’s cylinder banks are spread 65 degrees apart. After Ferrari began using this angle in its 1989 Formula 1 V12s, it trickled down to the 456 sports car in 1992. A 65-degree V-angle provides additional space for larger bores (more clearance at the bottom of each piston’s stroke), room between the cylinder banks for more voluminous intake manifolds, and a slight reduction in overall engine height. While it’s possible to maintain even firing with split-pin crank throws, Ferrari wisely avoided that potentially fragile complication. The result, with six straight crank throws, each carrying two connecting rods, is slightly syncopated firing intervals that alternate between 55 and 65 degrees of crank rotation. This subtle ticktock isn’t detectable from the driver’s seat thanks to Ferrari’s judicious powertrain isolation and intelligent acoustic measures.

Car and Driver’s 2018 test of a Ferrari 812 Superfast reported a 1,747kg kerb weight with a slight rear bias, 0–60 mph in a remarkable 2.8 seconds, and a quarter-mile clocking of 10.5 seconds at 138 mph. No one has verified the factory’s 211-mph top-speed claim, but that figure is certainly credible.

While all versions of the 812 – GTS, Superfast, Competizione – cease and desist after existing orders are filled, Ferrari’s F140IA 65-degree V12 will continue in the 2024 model year under the hood of the new five-door, four-seat Purosangue SUV.

Though Ferrari has boldly experimented with and/or produced engines with two, three, four, six, eight, and 10 cylinders, it’s most associated with V12s thanks to its loyalty to that configuration for three-quarters of a century. There’s little doubt that 12-cylinder engines have been instrumental to Ferrari winning respect as a hypercar producer. Last year, the brand built and sold 13,221 cars worldwide, reporting 19 per cent increases in both volume and revenue.

Count yourself fortunate if you’ve owned, driven, or even heard more than your share of prancing horsepower!