Numerous motorcycle marques have been reborn in recent decades, but few have approached the brightness – or the brevity – with which Laverda returned to the spotlight 20 years ago.

The SFC1000 prototype unveiled at Milan’s EICMA exhibition in November 2003 under the banner “The Legend Returns” was a striking superbike, powered by a V-twin engine from parent company Aprilia, whose name and orange paintwork brought to mind the thunderous machines with which Laverda had illuminated the 1970s.

But before the revival had truly begun, it was over. Aprilia’s finances worsened dramatically, and barely a year later the firm was taken over by scooter giant Piaggio, which cancelled the Laverda comeback before the SFC had come close to production.

Which was a great shame, especially for all who had been enthralled in the 1970s, when Laverda’s rapid road-burners and production racers, headed by the 750 SFC twin and Jota 1000 triple, had made it one of motorcycling’s most prestigious manufacturers.

The small firm from Breganze, in northeastern Italy, was often spoken of as the two-wheeled equivalent of Lamborghini, with good reason. Like the car company located 100 miles to the south in Sant’Agata, Laverda had begun by making agricultural machinery. And like Lamborghini, by the early 1970s it was better known for stylish, low-production sports models with prices to match their high performance.

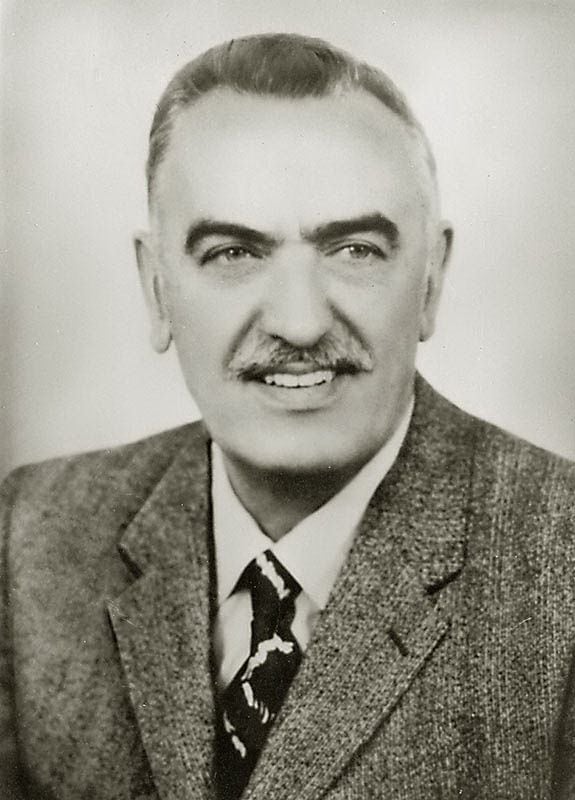

Laverda’s agricultural roots had been established by Pietro Laverda in the 1870s, and the family firm thrived for three generations. After World War II, Italy’s demand for cheap transport prompted a move into motorcycles, led by Francesco Laverda, Pietro’s grandson. The Laverda 75, introduced in 1949, was a single-cylinder four-stroke of 75cc capacity. It was quick and robust, and in the mid 1950s scored numerous class wins in the gruelling Milan-Taranto and Giro d’Italia road races.

Francesco Laverda’s ambition was to produce small, economical bikes to provide mobility for the masses. This worked well as production increased through the 1950s – but the arrival of inexpensive cars, led by Fiat’s 500, sent the Italian motorcycle industry into a tailspin. By the early 1960s Laverda was struggling, having failed with a string of scooters.

Francesco’s son Massimo, unlike his father, was an avid motorcyclist who owned a BMW boxer for everyday riding and an exotic Vincent Black Shadow for weekend fun. Massimo had the foresight to anticipate motorcycling’s move toward the leisure market – a view that was reinforced in 1964 when he spent several weeks in New York and Los Angeles, notably picking the brains of journalists at Cycle World magazine, before returning to Breganze convinced of the potential of large-capacity bikes.

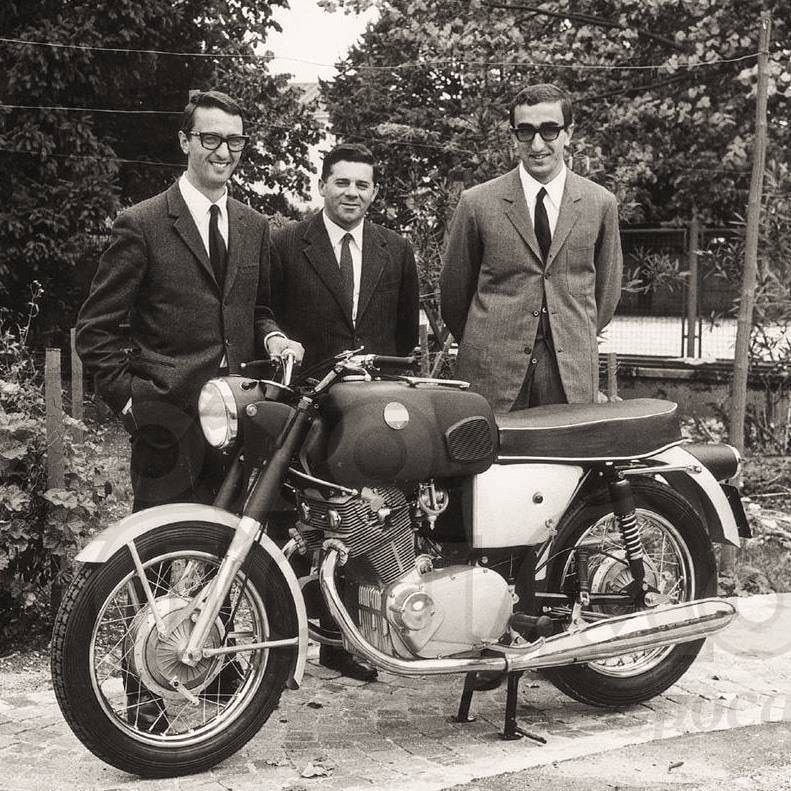

Massimo eventually convinced his father to change direction; or, as he later put it, “eventually I wore him down and he agreed to give me full rein.” The result was that in November 1968, Laverda unveiled an attractive, all-new roadster powered by a 654cc, SOHC parallel-twin engine whose look and layout owed much to Honda’s popular 250cc CB72. This was soon followed by a 744cc derivative that boosted output to 52bhp.

Although production remained low, Laverda was building a reputation for performance with reliability. By the early 1970s, the twin was available as the touring 750 GT, with options including crash-bars and panniers, and the sporty 750 S, with low bars and optional single seat. The 750 SF earned its extra digit with its Super Freni – a big front drum brake of the firm’s own construction. Laverda became known in export markets, too – belatedly in the US, where the bikes were initially marketed under the name American Eagle.

The outstanding early twin was the 750 SFC. The C of its name stood for Competizione, and it truly was an racing version of the SF, combining a tuned and beefed-up 70bhp engine with a modified frame and race-style half-fairing, seat unit, and rearset footrests. Orange paintwork aided identification in endurance events, including the Barcelona 24 Hours, where the SFC won on its debut in 1971.

The SFC also made a hugely desirable roadster. It was good for about 125mph, handled well despite weighing over 200kg, and its lean, minimalist style compensated for its high price and lack of comfort. Laverda updated it over the next five years with disc brakes, new suspension, and electronic ignition, while producing only around 550 units. Surviving SFCs are so highly prized that even replicas, created from more humble twins, sell for serious money.

If Laverda’s twins established the marque, it was triples that brought most of the fame. The initial 3C model (imaginative names had never been a strong point), launched in 1973, had a capacity of 981cc and resembled an existing twin with an extra cylinder, albeit with twin overhead camshafts that helped push peak output to 80bhp.

The 3C and later 3CL were followed in 1976 by the Jota, initially produced when the UK importers, brothers Roger and Richard Slater, tuned the big triple with lumpy camshafts, high-compression pistons, free-breathing exhaust, and rearset footrests. The Jota produced 90bhp, was timed at 140mph, won three UK national production racing championships at the hands of Slaters’ rider Peter “PK” Davies, and was adopted by the factory as an official model.

Of the era’s holy trinity of Italian superbikes, along with Ducati’s 900SS and Moto Guzzi’s 850 Le Mans, the Jota was the two-wheeled Burt Reynolds – handsome, hairy chested, and fastest of the lot if you were brave enough to hang onto its vibrating bars on the straights and wrestle it into submission through the bends.

Laverda created a follow-up by enlarging the triple engine to 1116cc and fitting higher handlebars and a larger seat, creating a slightly more versatile model simply named the 1200. Again, Slater Brothers developed a successful tuned variant, the Mirage; for some markets Laverda used the Mirage name for a 1200 without the tuning parts.

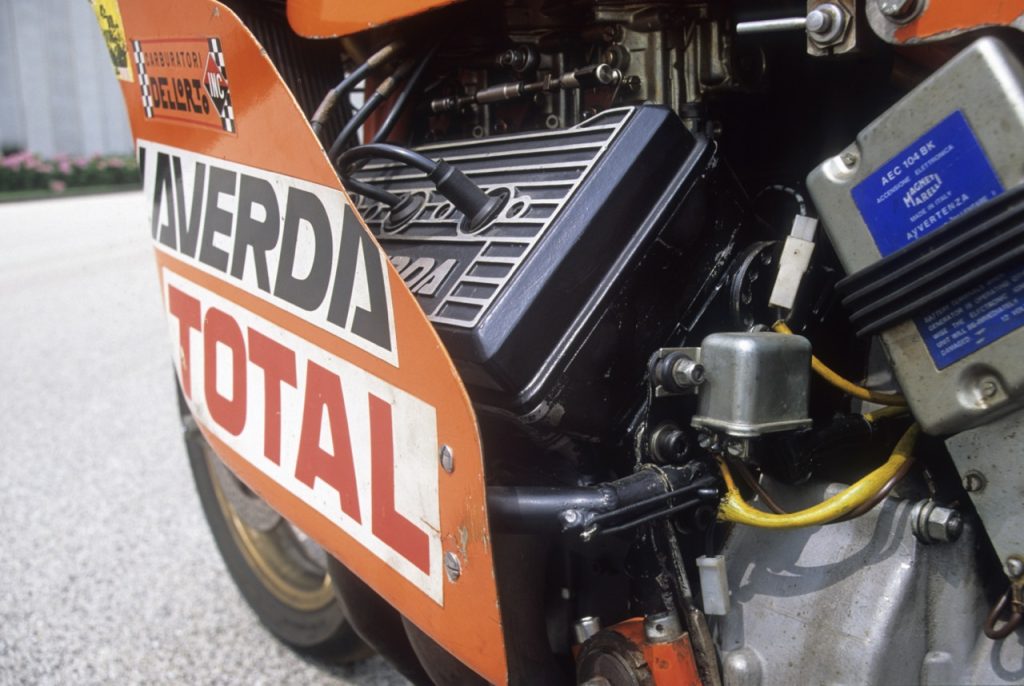

The most exotic and powerful Laverda of all was the V6: a 996cc, 140bhp, liquid-cooled endurance racer that competed at the 1978 Bol d’Or 24 Hours. It was speed-trapped at 176mph but retired after eight hours with a broken drive shaft and was never raced again – all of which merely added to its legendary status.

Laverda also built more down-to-earth bikes, notably a 500cc model that was called the Alpina in Europe and, for trademark reasons, the Alpino in the States. The tuned sports model was the Montjuic, launched in 1980 and named after the park venue of the Barcelona 24-hour race. It was a supremely aggressive charger that was too uncompromising and too expensive to sell in significant numbers.

By this time emissions regulations were closing in on the aircooled triples, but Laverda lacked the funds to develop a replacement. Instead, in 1982 it reworked the three-cylinder engine with a 120-degree rather than 180-degree crankshaft. The resultant Jota 120 was smoother but inevitably lacked some of its predecessor’s raw charisma. The same was true of quieter, less aggressive triples, including the RGS and RGA.

In 1984, the Jota was updated again, with a new twin-headlamp fairing. It was powerful and fast, especially when fitted with an optional tuning kit. When I rode the tuned triple in a magazine’s five-bike shootout on the Isle of Man, it impressed with its soulful character but struggled to keep up with Japanese superbikes led by Kawasaki’s GPz900R and Yamaha’s FJ1100, before suffering a major engine failure.

The following year Laverda, by now deep in financial trouble, released what would prove to be its last superbike: the SFC1000. Unlike its twin-cylinder namesake of a decade earlier, this SFC was not a racer but a sports-tourer. Laverda built and sold a limited run of 200, but production at Breganze ended soon afterward. A new cooperative, Nuova Moto Laverda, built a few small-capacity machines before quietly closing down.

That was not the end of the Laverda story. In 1993, the brand was bought by Francesco Tognon, a local textile entrepreneur. He established a new factory in nearby Zanè and financed development of a new parallel twin called the 650, featuring an aluminium frame designed by Dutch chassis guru Nico Bakker. By 1997, it had been developed to create the 750S, with liquid-cooling and 82bhp output. It was a promising bike but production finally ended the following year.

Laverda looked to have received a lifeline when in 2000 the name was bought by Aprilia, which also owned Moto Guzzi and was based nearby at Noale in northern Italy. Three years later, in Milan, Laverda was relaunched with that stylish orange prototype, powered by the V-twin engine from Aprilia’s own RSV Mille.

The potential for a badge-engineered Laverda superbike was clear, but by this time Aprilia had hit financial problems itself, following a sharp downturn in the Italian bike market. In December 2004, the firm was bought by Piaggio. With Aprilia and Moto Guzzi both requiring urgent surgery, the scooter giant had little incentive to invest heavily in a third motorcycle marque.

And that’s how things still stand, almost two decades later. Once-troubled Italian marques, including Benelli, Fantic, and Mondial, have since been revived under Chinese ownership; elsewhere, BSA, Norton, GasGas, Husqvarna, and Indian are also recently revitalised. Laverda remains asleep, awaiting a handsome prince – or more likely an automotive giant – that can awaken one of the most revered of two-wheeled brands.

The photo caption is probably wrong – Laverda was mainly known for its crop processing equipment, eg combine harvesters, not tractors.

The caption was indeed incorrect, Chris. Thanks for calling that out. It has been updated.

The bike pictured with the Laverda brothers and Mr. Zen is one of the 650 prototypes, not a 750 production GT.

The 500 Montjuich was a Slaters creation based on the production 500 Formula and was never produced by the Breganze factory. No production bike from Breganze ever sported dual headlights, these were fitted to aftermarket fairings, mainly Sprint, UK, in the case of the RGA Jota.

I owned an SFC1000 for a few years ,one built from parts after the factory closed. A beast of a machine but extremely charismatic . Wish I still had it in the garage,!!!

Please somebody make them again Sir Jim Radcliffe ineos maybe

Piaggio sadly view any potential Laverda as something that might attract people that might buy one of their existing brands like Guzzi so no real incentive to invest themselves and even less to sell the brand to someone else to do so

You missed out the corsa

Would Mike Donovan be formerly of Ross-on-Wye and like me an original member (6) of the International Laverda Owners Club? Please get in touch.

Correction, neither Fantic or Mondial are Chinese owned. Benelli yes, but the other two are Italian owned.