The sophomore slump. Difficult-second-album syndrome. For everything that’s a copper-bottomed classic out of the gate, there’s peril in trying to recapture that original lightning in a bottle. True Detective Season 2, anyone?

We’ve talked a lot about Harley Earl and his outsized (literally and figuratively) influence on the discipline of car design. He was a snappily dressed tyrant who combined long drinks with a short temper. With Alfred Sloan’s blessing, Earl oversaw the growth of GM from a motley collection of disparate marques in the twenties into an industrial powerhouse that was, by the mid-Fifties, the largest corporation in the world.

How on earth do you follow that?

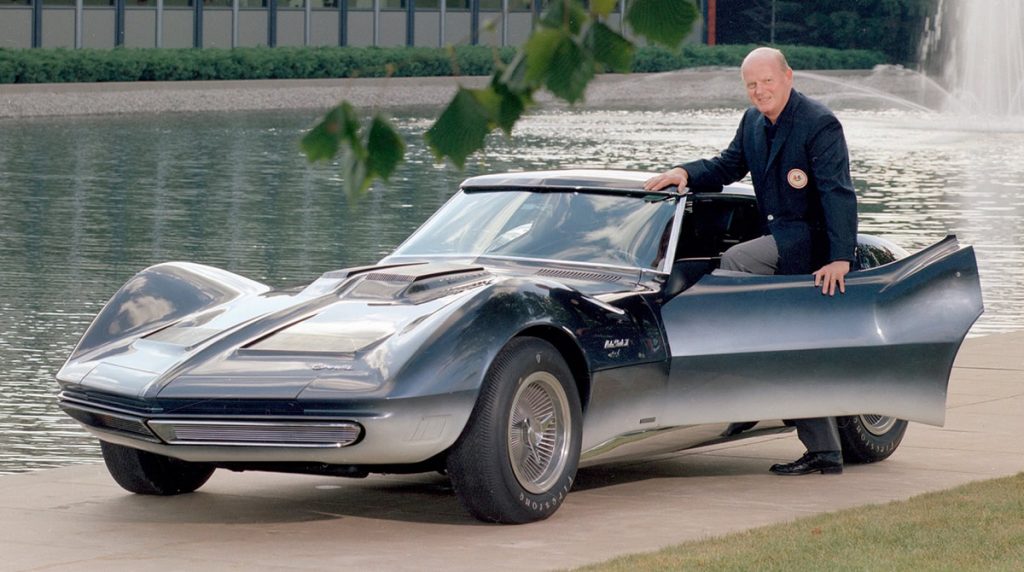

Bill Mitchell was hired by Earl in 1935. Anyone who could survive, let alone flourish under Earl was surely cut from the same cloth as the man himself. Within six months, Mitchell was head of Cadillac design. Despite having his own ideas smothered under Earl, Mitchell’s first car, the 1938 Cadillac Sixty Special would begin to show the themes he became known for: tauter surfacing, sharp creases, and a lack of ornamentation. By the time Earl retired in 1958, Mitchell was anointed as his hand-picked successor.

Like Earl, Mitchell was a big personality with a taste for sharp suits, sharp language, and alcohol. Subtlety and nuance was not a hallmark of either man, but Mitchell had a wicked sense of humour and a much more personable side; he’d feel the cut of your suit, rip you to shreds for it, and then diffuse the situation with a joke or an arm around the shoulder.

What’s more important than their similarities are their differences. Earl was a Hollywood showman and salesman, a hands-on synthesiser of other people’s ideas. He couldn’t draw himself and insisted on working orthographically. Mitchell, a trained illustrator from New York was much more international in his outlook and inclined to see the bigger picture. It was these characteristics that allowed him to drag GM design forward and eventually oversee a series of cars that reflected sixties consumers more sophisticated tastes and could be considered some of the high points of American car design.

The truth is, by the mid-1950s Earl was losing his touch. Well, perhaps that’s a little unfair; like so many pioneers in his field, the game had moved on and left him behind. Such was Earl’s abrasive nature and propensity for churning through young designers that another Earl protégé Virgil Exner, found his working methods so intolerable he left to progress his craft under Raymond Loewy at Studebaker. Exner eventually wound up at Chrysler and in 1955 introduced his ‘forward look’; much slimmer body sides and roof treatments that were a world away from Earl’s chrome-laden dreadnoughts.

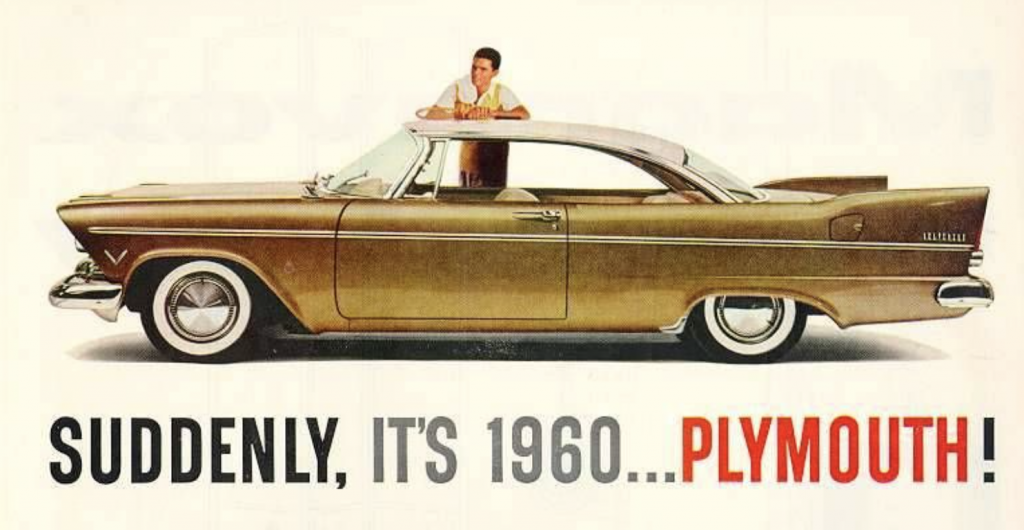

When the 1957 Plymouths were introduced with the memorable tagline “Suddenly it’s 1960!” it was all over. Future GM chief Chuck Jordan was so shocked seeing the ’57 Plymouths lined up outside their plant he immediately went and grabbed Mitchell and they spent the rest of the day eyeballing the competition. Earl was in Europe at the time, and returned to find all the ’59 cars had been redone in his absence. Outmanned, outmanoeuvred, and nearing retirement, such insubordination would have been unthinkable a few years prior.

Mitchell, having toiled for years in Earl’s shadow, was determined to make a complete aesthetic break from what had gone before. He knew the limitations in the way the GM studios had been operating up to that point. The external studios were extremely short handed and six-day weeks were the norm. Sheet metal changes for each model year meant there was little to no advance design work being done – they just churned it out, groaning under the weight of ever more chrome.

Contrast Earl’s ’58 and Mitchell’s ’59 Chevy Impala. The ’58 is very heavy handed with a deep body side, large chrome bumpers and a thick C-pillar with extraneous fake vents (and you thought these were a new thing, huh?). The ’59 is much leaner, lighter on its wheels due to the body side tucking under and has a slim pillar treatment that allows a more modern, airy glass house. It looks like it’s doing sixty just sitting there. More than that, the ‘59’s shape is beginning to flow around the corners of the vehicle, a legacy of Mitchell’s ability to sketch and visualise in three dimensions. The two cars represent a visual and metaphorical break between the two men.

Mitchell was not able to instantly unwind all of Earl’s work. For a start, Earl had enjoyed the protection of Sloan who had personally hired him. Sloan had retired in 1956 and so Mitchell had no such patronage. In fact, due to increasing costs (and not wanting one man to be bigger than the company) the GM higher-ups wanted to reassert control over the design department, and Mitchell wasn’t really secure until 1967 when Ed Cole became President. But Mitchell idolised Earl, keeping a portrait of him in his office and vowing to ‘never let him down’. This corporate resentment would continue to fester and resurface to devastating effect on GM design years down the line.

If Earl had invented the studio tools, it was Mitchell who really used them to liberate the design process. He saw himself and GM as a design leader. He staffed up the Tech Center properly and got involved much earlier in the design process, regularly setting the studios against each other in friendly competition to drive them to ever greater heights of creativity.

One of Mitchell’s early triumphs was the 1963 Buick Riviera. As befits his New York background, Mitchell was obsessed with European cars and envisaged a Cadillac with the stateliness of a Rolls Royce combined with the taut sportiness of a Ferrari for the Detroit country club set. The final design, originally sketched by Ned Neckles and finessed into greatness by Mitchell was rejected by Cadillac but gratefully found a home at Buick. It’s an absolute masterpiece – sharp, restrained yet perfectly proportioned and unashamedly American. When you consider there are only four years between this car and a ’59 Eldorado, it’s clear what a massive step forward it was.

The hits kept on coming. The 1963 Corvette (C2) looked completely different to its predecessor and yet was still unmistakably a Corvette. Oldsmobile engineers evaluated an E-Type and a Ferrari, and not really understanding the ethos of a tight, visceral manual transmission European sports car went and did what Detroit did best – the personal luxury car. The 1966 Toronado didn’t use its revolutionary front wheel drive powertrain for any particular advantage (certainly not in packaging) but simply existed as a magnificent monument to the American car as its own unapologetic thing.

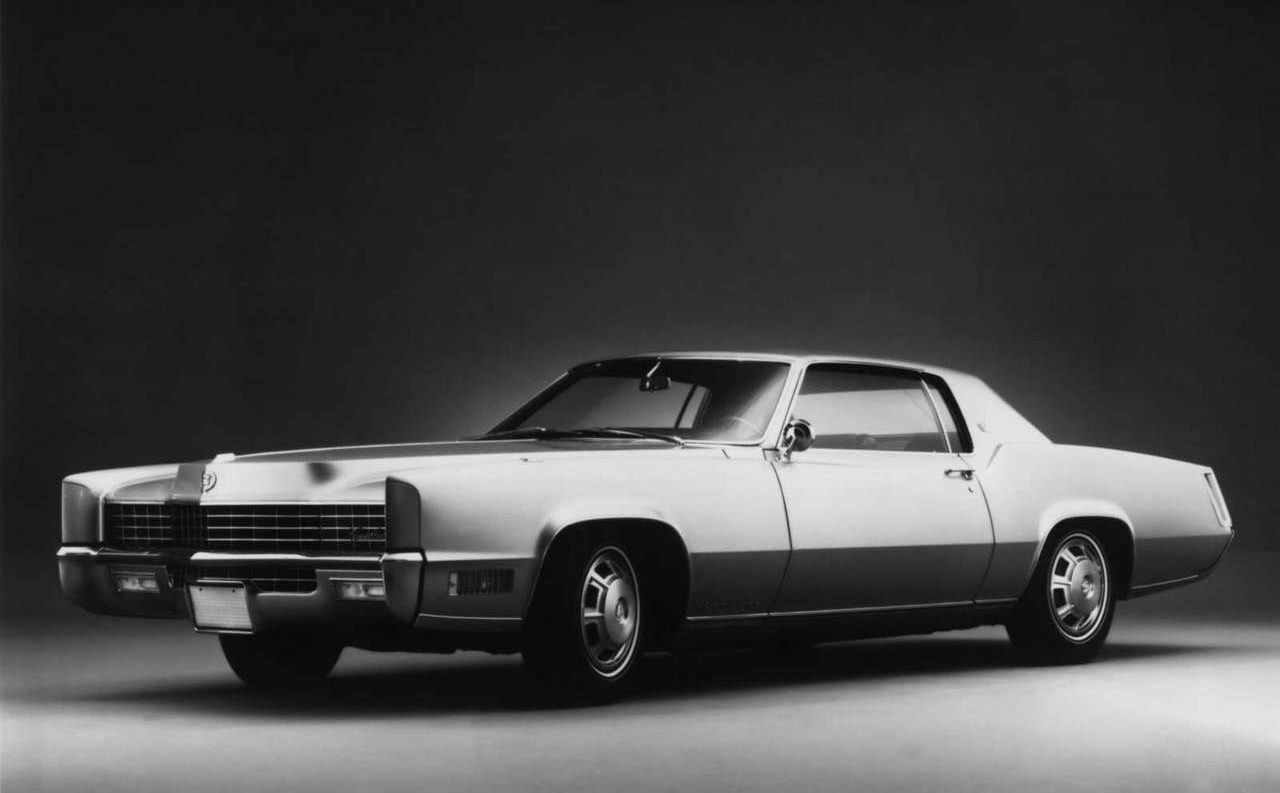

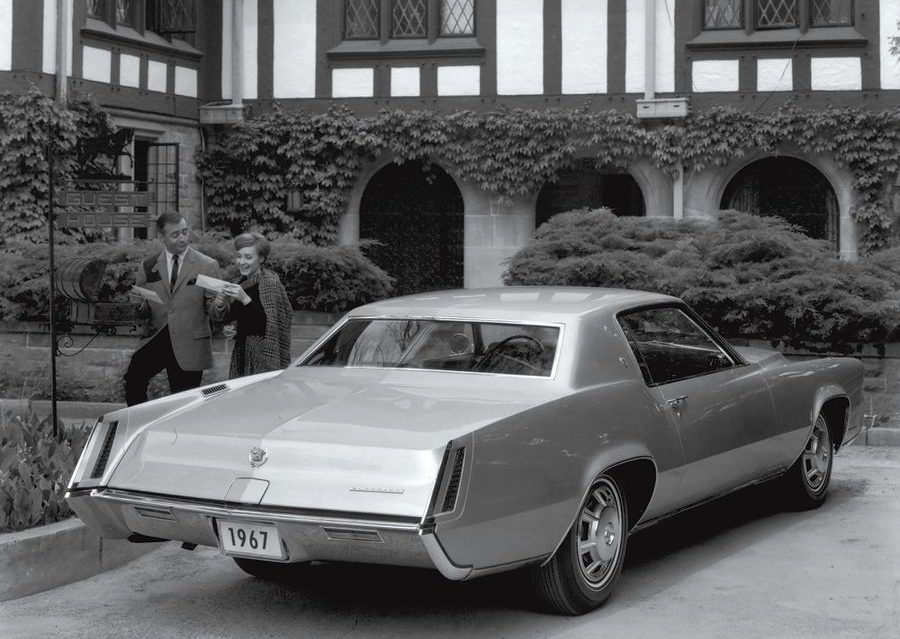

But for your humble author’s money, Mitchell’s finest hour is the 1967 Eldorado. Sharing its E-body platform with the Toronado and 1966 Riviera, this Eldorado is one of those rare cars that (with sympathetic updates to lighting, stance and glazing) could be in showrooms right now. Although the rear overhang dates the design somewhat, the rest is utterly timeless.

Every detail is completely integrated into the surfacing – not one part sticks out or jars against the whole. There’s terrific tension in the fender lines and just the right amount of taper towards the rear which still manages to hint at tailfins, giving a subtle reference to those earlier cars. The grille and hidden headlights are simple yet exude quiet authority – important in an American car that at the time genuinely was a rival for the best in the world.

Mitchell called his trademark look “London Tailoring”, but his real genius lay in taking sharp lines and restrained detailing and combining them with his beloved European influences to create something unique. Witness how the front of the 1970 Camaro references the 1968 Jaguar XJ6. He was a true internationalist at a time when the International Style was the zeitgeist.

Mitchell wasn’t fond of small cars, saying “it’s hard to tailor a dwarf” and “small cars are like vodka, people try them but they won’t stay with them”. He didn’t do too badly with the 1970 Chevrolet Vega, which for all its engineering faults emerged from Hank Haga’s studio looking every inch a miniature Camaro.

A bigger challenge lay in the “international size” 1975 Cadillac Seville, which was a new model based on the X platform (which underpinned the decidedly less glamorous Chevy Nova). Faced with increasing environmental headwinds and imported European competition, this was to be a smaller, but more expensive addition to the line. The idea was it would attract a younger and more discerning customer.

Mitchell, returning from Europe and seeing the initial models, insisted the rear windscreen was made more vertical like a Rolls Royce. Its single unbroken surfaces looked like they had been created with one sweep over the clay, and Mitchell termed it “sheer look”. It was a complete success, lowering the average age of the Cadillac buyer and providing a domestic alternative to the high-end European imports. The Sheer Look was next used on the downsized 1977 Caprice to great effect, as it was so successful it stayed in production with only minor changes until 1990.

Mitchell’s final car was the 1980 Seville. Giving in to what were by now the worst of his Scott Fitzgerald influences, Mitchell gave the car it’s controversial bustle back, feeling the earlier car too bland and needing something distinctive to mark it out. The effect of this was to attract an older generation of buyers, the exact opposite of what GM wanted.

In a further typical GM act of self-sabotage, Vice President Howard Kerhl deliberately overlooked Mitchell’s second in command (and chosen successor) Chuck Jordan. Instead he was replaced, upon retirement in 1977, with the supine Irv Rybicki. Kerhl hated Mitchell with a passion, and was determined that such a strong-willed person would never again rule the Tech Center. It’s no coincidence that Rybicki’s reign as vice president of GM design coincided with Roger Smith’s disastrous tenure as CEO.

Once Mitchell was gone, the management types at GM’s fourteenth floor had complete control over the Tech Center and GM design with disastrous consequences; by the late seventies GM was no longer a design leader and the domestic OEMs lost their hegemony on the American market. But the past might as well be another country, as a larger-than-life man such as Mitchell (or indeed Earl) could never survive in today’s corporate environment. Mitchell’s story demonstrates the importance of having someone with a clear design vision at the top of any OEM that considers design an important part of its identity.

And the years from about 1963 to 1975 are an absolute golden age. Chuck a marker over your shoulder and it’ll land on any number of American design classics from that period. The sheer confidence and beauty of any of those cars is staggering. Mitchell firmly believed that supply creates the demand – create desirable products and the customers will follow. This was proved in the numbers; 72.5 million cars sold during his time in charge.

An argument could be made, and I’m going to make it, that not only was Mitchell responsible for elevating GM design, his body of work is so strong it lifted the entirety of American automotive design as a whole because his competitors were forced to keep up. No one else was close; Ford and Vauxhall in the UK were mostly still shrinking old American designs in the wash and the Japanese had barely got out of bed and found their tracing paper. Only the Italians (whose influence spread far beyond the Old Country thanks to their work with BMW and British Motor Corporation) were even in the same postcode.

Most of us who get into this business, if we have any taste at all, would kill to have done one of Mitchell’s cars. These days, the OEMs doing the best work usually have a more sober version of him near the top of the hierarchy: to fend off management interference and to make sure their ideas are driven through with as little compromise as possible.

The rise of Kia certainly isn’t because of their bougie dealer experience; it’s because they realised that value is only part of the equation. Customers must want your vehicles on a reflexive level as well. Maybe another lesson current studios could learn from Mitchell is the benefit of the three-martini lunch?

This article was originally posted on Hagerty US.

Read more

Vision Thing: There’ll be no spinning in graves, actually

How Not To Build A Car, Part 3: Powertrains

AMAZING! Time-lapse engine rebuild of a Chevy 283 small-block | Redline Rebuild