Author: Roland Brown

Photography: Roland Brown

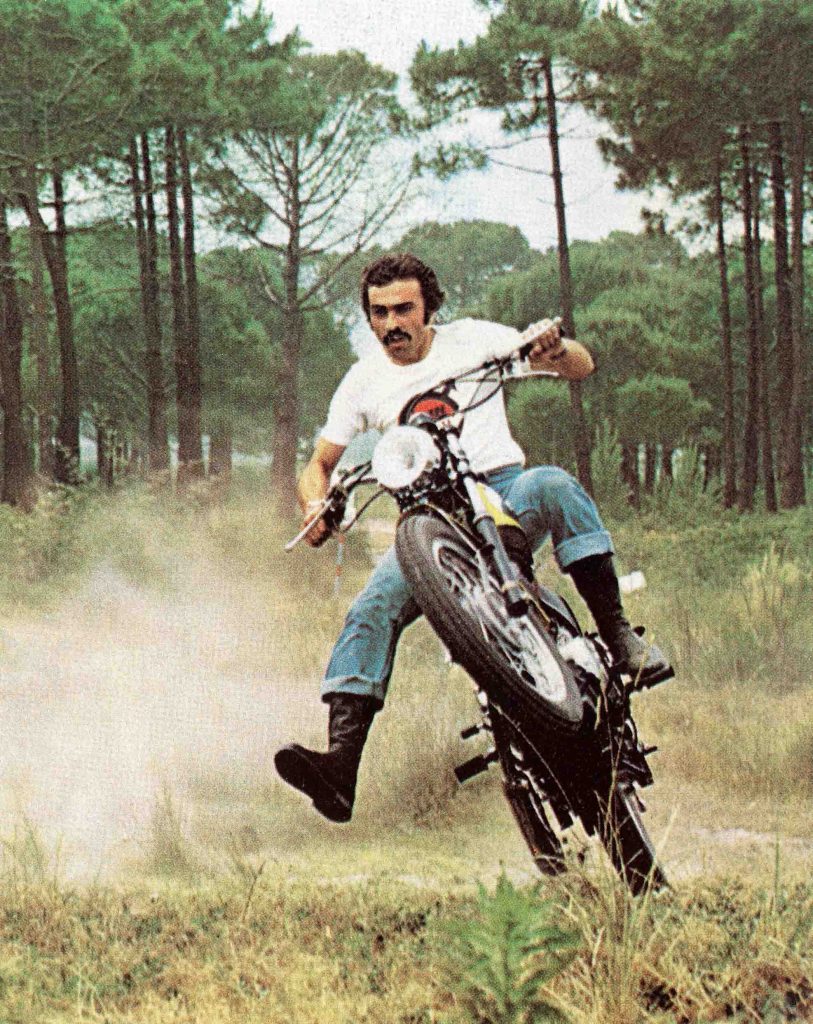

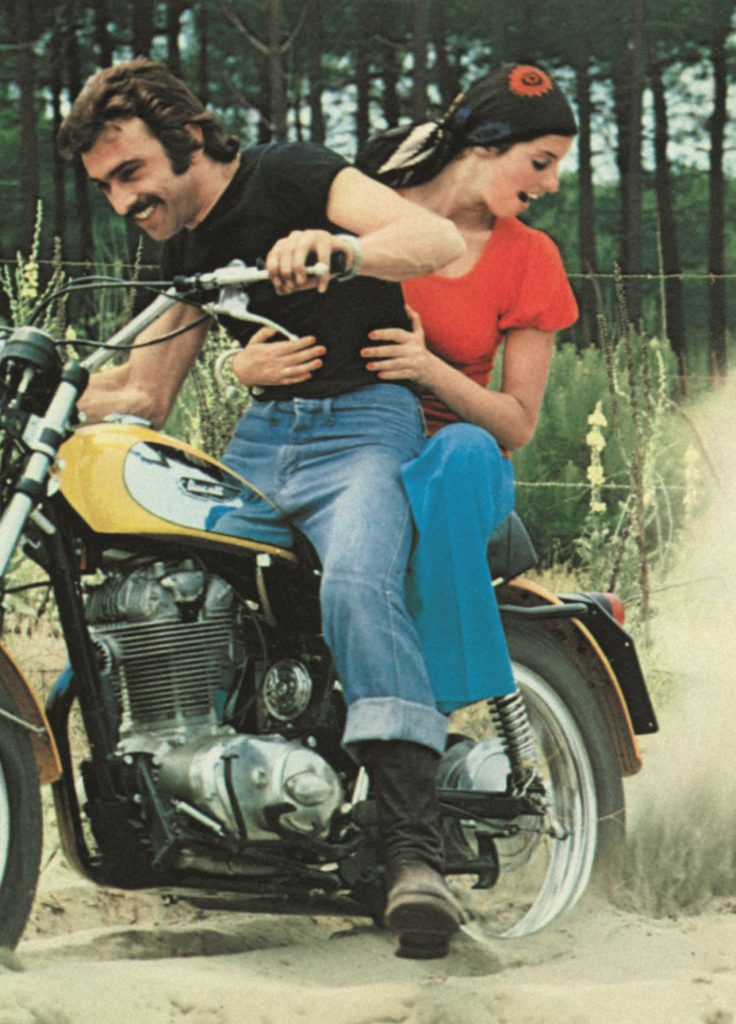

Ducati’s publicity photo for its Scrambler model of the early Seventies sums-up the appeal of motorcycling in that carefree, long-ago decade.

The handsome, dark-haired rider is wearing little more than a drooping moustache, white tee-shirt and denim jeans rolled-up to reveal stylish boots. One boot is off the footpeg as he wheelies down a woodland trail, rear tyre kicking up a cloud of dust in his wake.

Few owners of the Italian firm’s 1973-model Scrambler could ride it like that, but this was a mighty cool motorbike nevertheless. With its high handlebars, punchy single-cylinder engine, agile chassis and rugged styling, the Scrambler combined lively roadgoing performance with genuine off-road ability.

In many ways the stylish single was decades was ahead of its time. These days Ducati has a whole family of Scramblers, and almost every manufacturer produces versatile adventure models of various capacities.

There was much less choice half a century ago, although even back then Ducati produced a family of three Scrambler models, all of them visually similar, and with engines of 250, 350 and 450cc. The flagship 450 featured a new engine with desmodromic valvegear; the other two made do with conventional layouts.

The 450’s desmo system of positive valve closure gave little performance advantage in the relatively laid-back Scrambler’s case. Many Ducati enthusiasts considered this 350cc variant, which was simpler and generally more reliable, to be the pick of the trio, partly because it was easier to service.

The Scrambler had begun life in the early Sixties, as a descendent of the off-road competition models that Ducati had been building for events such as the prestigious International Six Day Trial. In the late Fifties, the firm’s 175 and 200cc scramblers were true racers, with tuned engines, racing exhausts, and special frames and brakes. But they were expensive and sold in small numbers.

In 1962, at the request of Ducati’s American importer, the Berliner Corporation, the factory introduced the first true dual-purpose Scrambler. This was a less racy version of the competition bikes, combining a new 250cc engine with a cheaper, road-based chassis.

This Scrambler’s frame, forks and brakes were identical to those of Ducati’s 250cc roadster, and the shocks differed only in having slightly softer springs. The model was updated throughout the Sixties, keeping its unsilenced, straight-through exhaust system but gradually losing its competition image as it gained improved lights, a battery, and roadster-type tyres in place of its original knobblies.

The biggest change came in 1968, when Ducati introduced the so-called “wide-crankcase” single-cylinder engines, which were considerably stronger than the old (“narrow-case”) units, although also heavier.

This year also saw the arrival of the Ducati 350 Scrambler which, like the other models, was sold mainly in Italy and the US, where it was known as the 350 SSS (Street Scrambler Sport) or sometimes the SCR (SCRambler). With its high, wide bars, tiny fuel tank, short seat and exposed air-filter housing on the right, this was essentially the Scrambler that would be sold, with few changes, for the next seven years.

The motor had a capacity of 340cc, and featured a high-compression piston, high-performance camshaft (driven as always by bevel gear), 29mm Dell’Orto carburettor, and a shortened roadster silencer. It revved to 7500rpm and produced roughly 25bhp; no figure was quoted.

Other new features of the Ducati 350 Scrambler, which was followed into production by the near-identical 250cc version a few weeks later, included a new frame, longer and stronger front forks, plus rubber gaiters protecting not only the forks but also the rear shocks.

The first bikes’ fuel tanks were red, black or white, with painted silver sides. But by the end of 1969, Ducati had introduced the yellow and orange tanks, with chromed sides, for which the Scrambler would become known.

This 1973-registered 350 Scrambler, which had spent most of its life in Italy, was original and unrestored, so its orange-and-chrome tank was understandably rather worn in places. But the little Duke was in pretty good condition for an elderly dual-purpose bike, thanks partly to having only 27,000km on its clock. Even its lack of suspension gaiters was correct; in what was presumably a triumph of style over practicality, the Ducati 350 was no longer fitted with them by the time this bike was built.

Neat original features included the winged Ducati tank badges, the filler cap with its little arm to help you open it, and the plastic tool bag in place of the left side-panel.

From the fairly tall seat, it was the slimness of the tank, which held just 10 litres, that made most impression. It was dwarfed by the width of the cow-horn handlebars, below which sat a pair of small black-faced clocks plus the knob for the friction steering damper.

Despite the kickstarter on the left of the engine, firing-up the Scrambler was easy. Just turn on at the headlamp, ease over the piston until compression, pull in the decompressor on the bar, and kick.

The single-pot motor came to life with a fairly restrained thumping sound from its silencer – first time, every time. Then I was flicking into gear with my right boot, and heading off up the road with the Ducati feeling enjoyably lively.

With only about 25bhp to call on, the Scrambler was never going to be super-fast in a straight line. But the single was light at 133kg dry, and its motor was torquey and responsive enough to give a reasonable burst of acceleration, heading for a top speed of around 90mph.

That combined with the sweet five-speed gearbox to make the single good fun on the winding country lanes on which I started my ride, and also the gravel-covered track on which I gave its off-road ability a short test.

On the open road it pretty soon became clear that although the Ducati was capable of holding a steady 70mph or more, its comfortable cruising pace was nearer 60mph, about 5000rpm in top gear. Above that point the single-pot motor’s vibration through seat and footrests soon became uncomfortable.

There were no such limitations with the chassis, which confirmed just why Ducati’s single-cylinder combination of rigid frame, light weight and firm, well-damped suspension was regarded as close to sporting perfection in the early Seventies.

There haven’t been many dual-purpose bikes over the years whose frames could be successfully used in road-racing, but that was true of the Scrambler. Its frame comprised a large-diameter spine plus a single downtube that bolted to the front of the engine. The powerplant was used as a stressed member, to good effect.

Steering geometry was conservative, and the front wheel was a big 19-incher. But the wide bars gave enough leverage to make the lightweight Scrambler easy to throw around in corners, without ruining its stability at speed.

The Ducati 350’s firm suspension added to the bike’s agile feel, although it was easy to see why the tester from US magazine Cycle World thought the front forks too harsh for off-road use, and preferred the shocks on their lowest preload setting.

My only problem on the road concerned the Pirelli tyres, which looked old enough to have been the original fitment, and prevented me from making the most of the slim Ducati 350 Scrambler’s generous cornering clearance. At least the brakes worked reasonably well, despite being fairly small single-leading-shoe drums at each end.

There was also plenty of steering lock, which would have helped make the manoeuvrable Ducati an excellent town bike. Ironically the ageing, lightly treaded tyres weren’t shown up too much by my gentle off-road excursion, where the bike acquitted itself well on loose stones and dirt.

I wasn’t tempted to try a more ambitious trek. Like so many of its modern namesakes, this Scrambler was really a roadster with dirt-bike styling plus a little off-road ability, rather than a genuine dual-purpose machine.

That did not prevent the Scrambler family from being popular, although few were exported to European markets, until Ducati abandoned its single-cylinder range in 1974. Among the last Scramblers were 250s produced by Mototrans, Ducati’s Spanish subsidiary, some of which were sold in Italy.

After a gap of almost 40 years, rumours grew stronger that Ducati would release a new-generation Scrambler until 2015, when the Bologna firm finally did so. That year’s 803cc model heralded not just a family of relatively simple, retro-themed aircooled V-twins but a distinct Scrambler sub-brand.

The current Scramblers are much bigger and more powerful than their Seventies namesakes. But the visual connection is clear, and their attitude is much the same. That moustachioed, wheelie-pulling star of Ducati’s old publicity photo would surely have approved.

Have you had the pleasure of riding or owning the iconic Ducati 350 Scrambler? We’d love to hear your stories in the comments below.

Read more on Ducati

Ducati 916: A Bike Even Die-Hard Car Fans Want to Own

The 916 Changed Ducati’s Trajectory Forever

Buying Guide: Ducati 916 (1994 – 1998)

The 450 was nicknamed the “shin-breaker” in Italy (‘spacca stinchi’), I presume for the kick-start springing back. My friend had one when I lived there decades ago. Nice bike.

I have a 1972 Desmo 350 that I used to road race, was a fun time. I also have a 1974 Desmo street legal scrambler, original with very little mileage.

That guy in the advert pic was definitely in the process of falling off. Hope he caught it! Dinky little bike.