In December, our comrades in the US named the sale of a 1954 Ferrari 500 Mondial Series I by Pinin Farina, #0406MD, as the most significant of 2023. Ordinarily, an old Ferrari race car changing hands for more than a million pounds would not constitute anything newsworthy in our niche little world. In this case, the car – if you can even call it that – is far from ordinary. It is a twisted mass of bent, dented, and corroded metal, the victim of a racing career, a massive crash, time, and a building collapse amid a 2004 Florida hurricane. As Monty Python would say, “This Ferrari has ceased to be! It is no more! It is an EX-FERRARI!”

The buyer, who did not bid on a parrot, seems to feel otherwise. Yes, it may look like a near-£1.5M paperweight now, but with at least that much more cash in reserve to pay for the mother of all restorations, this might once again be a 1954 Ferrari 500 Mondial. Even if said restoration involves, as Hagerty’s US Price Guide publisher Dave Kinney mused, “every single nut and bolt.”

When most people outside the car world hear about such a plan, they wonder: Is the end product even the same car? Indeed, many people within the car world do too.

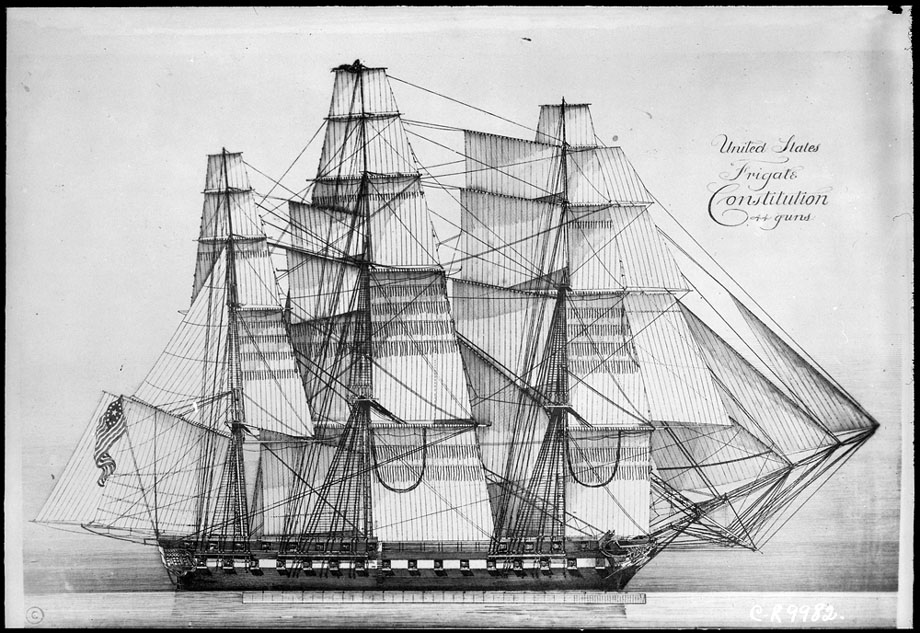

That question got me thinking about a centuries-old philosophical paradox, one that may ring a bell. It’s called “The Ship of Theseus.” Some of the world’s most brilliant thinkers have wrestled with the problem and examined it in various ways, but the crux of the question is fairly straightforward.

Imagine a sailing ship whose best days are behind it – rotting planks, tattered sails, empty bottles of grog, et cetera – that gets a complete and total makeover in which every single component is replaced with identical, shipyard-fresh components. Is it still the Ship of Theseus when the final plank is laid, or is it now… something else?

In other versions of the conundrum, the worn parts are subsequently rebuilt into another ship, producing two ships in total, one new and one old. Which, then, is the real Ship of Theseus? In other versions still, pieces are replaced bit by bit over a period of many years, engendering other questions such as, “If the ship at the end of the transition is no longer the Ship of Theseus, at what point did it stop being the Ship of Theseus?”

If your head hurts, don’t feel too bad. It’s a paradox. There is no definitive answer. However, in trying to come up with one, philosophers dredge up all kinds of titillating ideas and explanations. Old cars, it turns out, introduce fascinating nuances to this age-old metaphysical quandary.

“The Ship of Theseus is one of many different puzzles that puts pressure on intuitive judgements about artifacts, starting with the idea that ordinary artifacts survive gradual change,” says Dr. Maegan Fairchild, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan. “Cases of art restoration are already challenging enough, and interestingly, different issues arise when we start thinking about mass production. Classic cars are a tremendously rich intersection of these questions.”

Fairchild admits she is not a car enthusiast, but her study of metaphysics and aesthetics examines how some objects seem to deal with change successfully while others don’t. “In the Ship of Theseus, we’re negotiating how much of the ship we can change. You can take your car to the mechanic for new brakes and when you pick it up a few days later, it is still the same car. But imagine, instead, it was my grandfather’s truck that only he had ever repaired. I’d be quite reasonably furious if you had it fixed at a shop, by some other mechanic, without my permission. It’s a case where an ordinary object is more than just its physical parts.”

Cases in which a car is with its original owner speak to something similar. The moment a car is sold to a second owner, it loses that quality.

Questions of restoration or conservation can get even thornier. Often, the goal of such endeavours is to “protect an artifact from other changes – the rust, for example, that might spread to the rest of the car – that threaten to destroy it,” Fairchild says. “But with mass-produced objects, are we trying to restore their condition or their function?” What’s more important, how it looks or how it actually drives? And what does “original condition” mean? Is it the design? Parts? Materials? How it operates?

Ensuring a car persists with all of its original parts may, in some instances, doom it to never run again if the caretaker does not have the ability, knowledge, or tools to make it work reliably as designed. Certain pre-war cars and technologies come to mind. Is it more “original” in that state, or, if it runs and drives but uses, say, an electric starter instead of one activated by a vacuum switch?

Originality and restoration are concepts that depend on perspective, Fairchild argues. “Going back to my grandfather’s old truck, restoring it to the out-of-box condition would make it valuable to someone who cares generally about that model, but in the process you’d be destroying the thing that I personally care about. The stakeholders matter here – the car may be of interest as a historical artifact, sentimental object, art object, functional object, or even a financial investment.”

Nobody has explored these discussions from an automotive perspective in greater detail than car collector Miles Collier, founder of the Revs Institute and author of the fantastic book The Archaeological Automobile. On the subject of the Ship of Theseus, his mind immediately goes to a 1990 English court case concerning whether a 1929 Bentley race car known as Old Number One could truly claim that title, given all of its changes in the intervening years.

“The car had experienced so many modifications and evolutions in and out of period that there was a real question of whether the new buyer had the authentic item or a pile of parts from subsequent evolutions,” Collier explains. “The judge determined it would be hard to argue the car was Old Number One. But if there was anything that could be Old Number One, this was it.”

In Collier’s mind, it was the proper conclusion.

“Ultimately, the reality of material things in a material world is that everything vanishes and disappears,” says Collier. “The only thing that survives the ages is essential, called The Platonic Aspect – the design and its conception, in the case of a car. We have to accept that matter of any kind is always in a state of becoming, transitioning, into one thing or another.”

Following that thread, Collier has a particular view on restoration.

“All restoration is fictional. That doesn’t mean it’s bad, but when you’re doing it, be aware you’re introducing fictional artifact as the kind of methodology, materials, and choices. Even the very fact that you are a person of the 2020s dealing with a car from 1935 means your values, your perceptions of the world, are limited to the scope of this moment. If it’s an 8C Alfa, you know it’s worth $15 million or something, and that makes you want to be careful and meticulous. But in 1935 the 8C was simply a product that Alfa Romeo needed to go down the road and eventually make some money. The factory approach was to have great fit and finish on what the customer could see, but on what wasn’t visible… not so much. That kind of thing is extremely difficult to replicate in restoration.”

Collier’s view that all restoration is fictional has a parallel in philosophy. Mereological essentialism is the view that no object can survive any change in its component parts – that the moment a car drives off the production line and microscopic bits of rubber wear off the tyres, it is no longer the same car.

“From that point of view,” Fairchild says, “the sense that there can be any continuous object in existence requires some kind of fiction-telling. In real life, mereological essentialism is usually plausible only in rarefied cases. What it does is get us a clean view of what is important to objects.” Think of, for example, driving gloves that Paul Newman wore; we understand that the leather may have cracked and aged, but we still treat them as the same pair of gloves. The storey that we tell ourselves, the one that matters most to the object, is that this material was once on Newman’s hands.

Still, for Collier, the most intrinsically valuable and culturally significant cars are the super-rare “all-there” examples that survive unmodified from their original state. Unmodified but not unmarred; unlike Han Solo frozen in carbonite, cars are real-world material objects that suffer degradation even in the best of storage conditions. The value of such cars, in part, is their testament to the vehicle’s original configuration that serves both as a historical record and as an example to guide future restorations of similar cars.

“The important thing is to maintain the role of archaeology, which is to maintain the vehicle’s connection to both past and present. However, I’m sympathetic to wanting to make things more practical, usable, convenient. I would much rather have an old car that has had minor modifications but is usable, rather than a technically perfect thing that nobody drives so it goes into the junkyard.”

So what about the destroyed Ferrari? Is it still the same car?

“The 500 Mondial is evocative,” Collier says, “and [after the fact it will be] maybe not so different from cars with what I call anonymising restorations – in which every element and indicator of the car’s idiosyncratic history make it an individual rather than the one that is one of a series of industrial objects.”

Some in the hobby assign special meaning or value to a factory restoration from, say, Aston Martin, Jaguar, Ferrari, Porsche, or Mercedes-Benz. However, Collier doesn’t correlate those services with any greater authenticity than he would another top-tier operation.

“A replica made with authentic parts on which every original material has been transformed, and in which everything fits perfectly and there is no sign of wear, has nothing to tell us about the car from the past. It can, however, have some value in terms of how that car in the past operated, particularly if the mechanical restoration was done with fidelity to the original systems.”

Despite what some owners and experts deem to be original, there are numerous “documented” cars out in the ether that are anything but. Kinney, the Hagerty Price Guide publisher, remembers one in particular:

“I know of a Ferrari that in the 1970s was wrecked – and I mean it basically fell off a cliff, so it was destroyed. I don’t think anyone who owned the repaired car since then has an idea there was ever damage. The point is that, at the time, it was never a particularly important car, so all of the work was done in an Italian body shop where pieces were either fabricated or parts were purchased from the factory. Now, it’s aged appropriately so nobody would ever come to the conclusion that this has happened.”

Like it or not, money is often a critical factor at this tier of the collector realm. Certain truths are not the sort owners want to go digging for, as any indication a car is not what it purports to be could come back to bite the owner upon resale. We should point out, however, that wholesale bodywork, in particular, makes no difference for some cars while it means everything for others:

“In the world of Cobras,” Kinney notes, “a re-body is a huge detriment to value because people want to protect the authenticity of the originals amid all of the replicas out there. But in other worlds a re-body is an improvement; you can buy body shells for a Mustang and it’s known as an acceptable substitute. The same is true for some British cars.”

In some ships, it seems, an entirely replaced hull is no big deal. However, the status that originality represents, Kinney wagers, can play an important role.

“There is an element of elitism that surrounds the car when an owner is able to declare it all-original. And then, be careful what you wish for: The cars that we covet now, almost all of them, at some point existed as used cars that weren’t worth very much and were treated as such. This is especially true of race cars.”

Race cars, especially those with notable competition history, tend to be worth a lot of money. Big money means big incentive to ensure a car’s survival, and even the most heinous damage, abuse, or modification may be washed over if the financial juice is judged worth the squeeze at the other end of the restoration.

“Look no further than Ferrari Classiche,” says Rudi Koniczek, a veteran high-end restorer with a particular expertise in Mercedes-Benz 300 SLs. “All they need is a chassis number. Fifties and Sixties race cars were trashed, wrecked, burnt to the ground, and generally clobbered. People died in them. However, if a car like that raced at Le Mans and there’s a fender left or chassis number, someone is gonna build a car around it.

“It’s not so different with Mercedes, either. I’ve fixed cars that had been completely wrapped around telephone poles or destroyed in house fires. Cars like that can go on to win shows.”

At this tier, the invisible rules that seem to govern what cars are deemed worthy, or valuable, can seem arbitrary and even alien. As an owner and a restorer, part of the process is navigating that labyrinth and deciding what rules you choose to follow, followed by what constitutes bending versus breaking them.

“Let’s take an alloy-bodied 300 SL, cars that were very fragile,” Koniczek says. “Many were re-skinned and rebodied. If a perfect, flawlessly restored alloy car is worth $7M, what about an original example that is so screwed up you wouldn’t drive it? That’s not an easy judgement.”

As a metaphysician and philosopher, difficult judgements come with Fairchild’s territory. A pretty good heuristic – a mental shortcut for solving similar problems of a type – for Ship of Theseus puzzles is tracing the history of a given object.

“If what is essential to an object is its causal history, the storey that we tell about it concerns its path from creation to now,” she says. “Like a winning race car, or a car that belonged to an important celebrity, sometimes that history is what we care most about. Think about sourdough bread that uses the same starter – what matters is not the particular bits of the bread like the flour, but the continuity from the source. Often this is the best approach to apply to complicated objects that by their nature are going to incur a lot of causal change in their lifetime, because of wear and tear. Houses are another good example.”

If history isn’t of primary importance, maybe it’s how the object is used. For race cars competing in period, their chief focus was maximum performance. From that point of view, individual parts did not always matter. A team might swap engines, transmissions, or aerodynamic parts without a second thought; it follows that what is essential to that object is that it continues to be treated that way when it is used on the race track now. Whatever changes it experiences simply become new chapters in the storey.

Jazz music, another discipline that cares deeply about what its creators and practitioners intend, offers an interesting parallel. “In many jazz pieces,” Fairchild says, “improvised sections are extremely important. But novelty with each performance is part of the experience – it would not be a proper rendition of the original if the music is repeated exactly from a previous performance.”

A different heuristic might be making sure the object has its essential parts – number plate, engine, transmission, et cetera. This is particularly difficult in cars, though. There are just so many parts, combined with the understanding that some – tyres, oil, brakes – are by definition meant to wear, while others are meant to last much longer. Even still, two identical cars with identical parts may not be identical in their significance. The final air-cooled VW Beetle ever built is a lot more important than the twelfth-to-last.

There are no easy answers here, which is part of what makes these questions so interesting. As sold, the Ferrari 500 Mondial in question did not have its original 2.0-litre Lampredi-designed engine but rather a later, still-period-correct 3.0-litre engine. Does this matter? Apparently not to the buyer, and, as collector car analyst Rick Carey points out, it likely helps that Ferrari did sell 750 Monzas with this engine in the ’50s. After all, nobody expects that the car will be original when the entire thing will have to be rebuilt almost entirely from scratch.

What matters is that the car is understood to be what it professes to be. And on the other side of its restoration, the car’s right to call itself Ferrari 500 Mondial #0406MD will be examined, judged, and evaluated by many interested parties. It’s their perspectives that will carry the most weight.

Our guess? Given the dollars and reputations in play, the end product will go over a bit better than Monty Python’s distressed parrot owner looking for recompense:

SHOP OWNER: “Sorry gov, we’ve run out of parrots.”

CUSTOMER: “I see, I see, I get the picture.”

SHOP OWNER: “I’ve got a slug.”

CUSTOMER: (glares) “Does it talk?”

SHOP OWNER: (shrugs) “Not really, no.”

CUSTOMER: Well, it’s scarcely a replacement, then, is it?