To notice the soot clinging to most of the Victorian edifices around Britain in the mid-20th century, drop-top motoring would have been the last thing that most doctors would have recommended.

And it had better be boiling hot if that cumbersome, nail-breaking hood was to be lowered. Very few new cars came with a heater as standard, so your knees were likely to start knocking in the back-draught (why do you think car rugs were invented?) as you trundled along.

Still, there were few finer motoring experiences than burbling through the English countryside with the roof down and the family on board, the wind trying to dislodge Brylcreemed locks while the fields and hedgerows rolled by either side. Most of the very earliest cars had exposed the driver and his passengers to the elements – like a horsedrawn carriage – and it took until the early 1930s for saloon cars to become the norm.

After the Second World War, many of those who could afford a new car were of the ilk of Corporal Jones from Dad’s Army; then, the Boer War didn’t seem that long ago and, as for driving, well, they were stuck in their ways. Full four-seater open cars were still very much in demand.

The trouble was, a fetish for fresh air was at odds with the average car’s technical advancement, as family cars increasingly adopted unitary construction techniques. This method of manufacturing a car abandoned the old idea of a chassis frame on to which a separate body could be fitted, replacing it instead with a fully-welded single unit, often called a monocoque.

This was cheaper to produce, for sure, but it was also considerably lighter and yet stronger; the structure was rigid, while noise and vibration were reduced, making for a smoother and less jarring driving experience.

With a separate chassis, bodywork had been easily interchangeable, a bit like Lego. With a monocoque, if you wanted to turn the car into a convertible, there was a problem: in short, if you chopped the roof off, the innate strength and rigidity was compromised.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, the few cars that clung to the old separate chassis concept were easy to offer as both saloon and convertible. The Austin A40 Somerset of 1952 was a perfect example, as was the broadly similar A70 Hereford; it was easy to offer a convertible for the small but stubborn demand that existed – from some 170,000 Somersets, only 7243 were convertible Coupes, they cost £774 against £727 for the ordinary saloon. Of over 50,000 Herefords there were just 266 Coupes.

Ford wanted to offer a similar choice on, for instance, its first generation Zephyr in 1953, but this entailed a lot more work because it was a unitary car. The top was sliced off by a contractor, with seriously strong metal cross-bracing added to the structure to stop it bending in the middle. A mere 4048 of these MkI Zephyrs were so modified, from a grand total of 148,000.

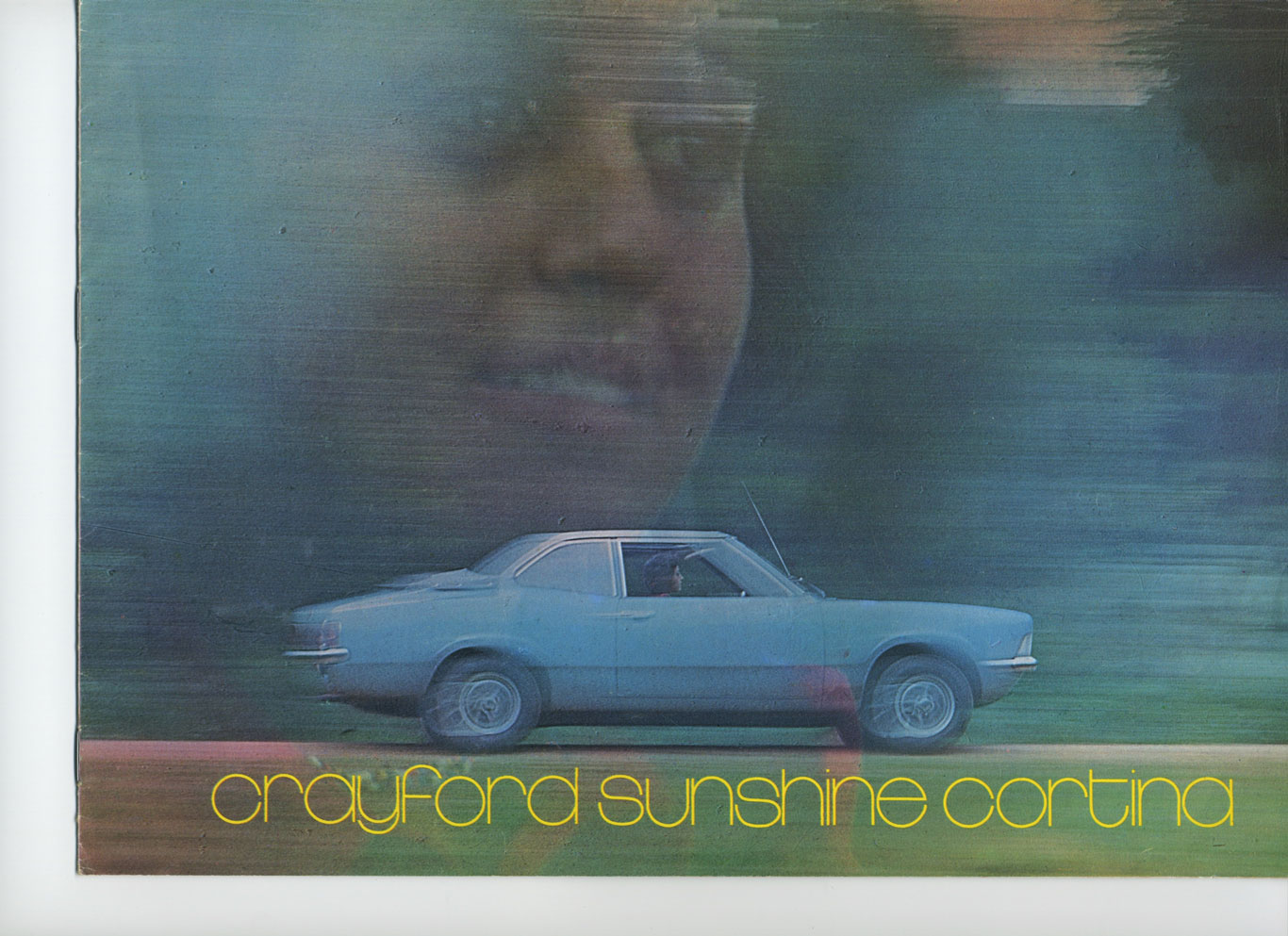

Ford wouldn’t give up easily on its small-scale convertible range, though. It continued with the MkII Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac series, which looked particularly glamorous in open form. Hillman, too, would not be deterred from including a topless Minx in its range, right into the early 1960s. This was despite the massive inconvenience of using a small London factory 100 miles away from its main plant to modify them. Only in 1964 with the last of its Super Minx convertibles in 1964 did Hillman give up. And if you wanted a four-seater open Ford in the 1960s and ‘70s then you had to seek out Crayford Auto Developments, who could expertly cut-and-shut a Cortina, Corsair or even a Capri with tacit Ford approval.

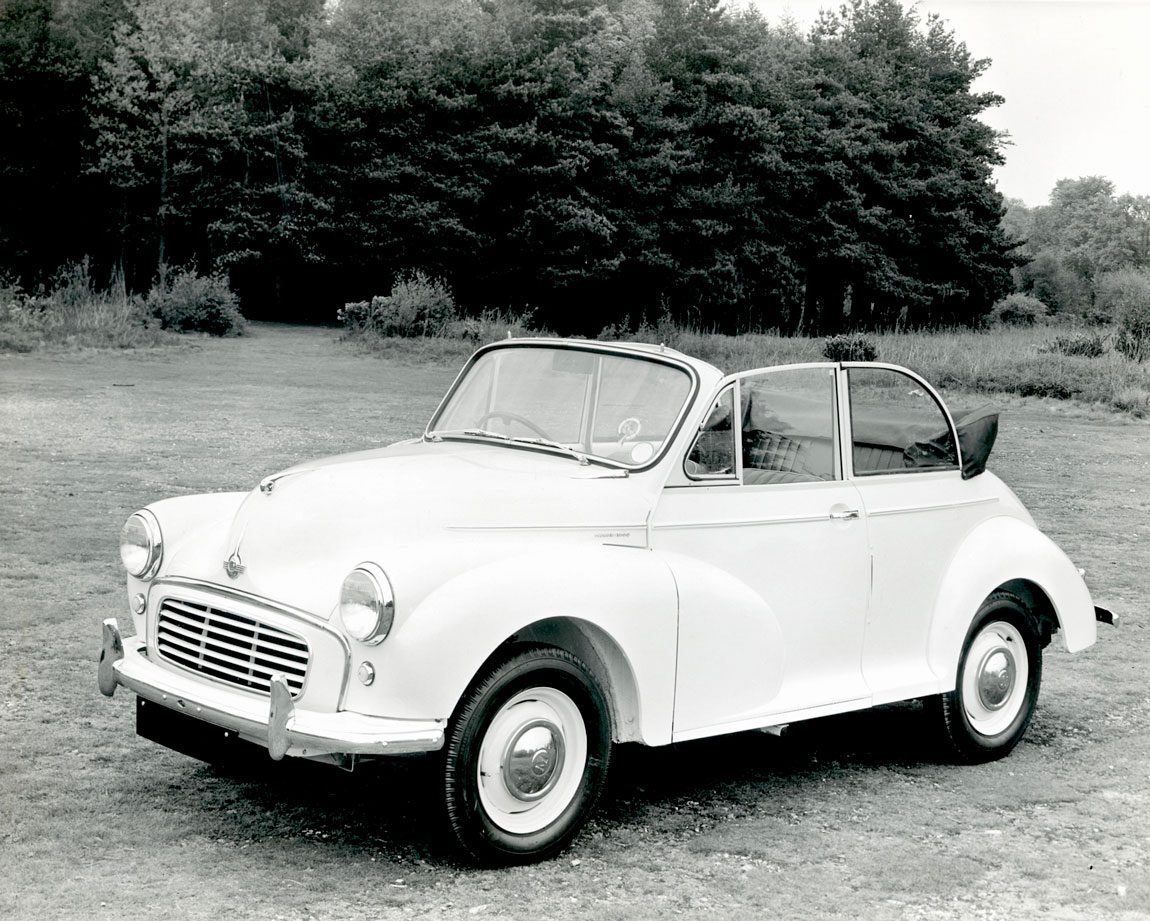

Morris was one marque that did sell decent numbers of affordable drophead cars, with its Minor Tourer. With a simple strengthening job done at the Cowley factory, they still accounted for just 6% of Minor sales but as almost 1.4m were sold in total this was quite a lot of soft-tops.

However, the Triumph Herald breathed exciting new life into the genre in 1960 after its manufacturer took the unusual decision to return to separate chassis construction. Together with the Morris Minor, the Herald was the obvious choice for any family motorist with a love of the great outdoors but a weather eye on his budget.

Mind you, compared to the snug-fitting hoods of today, neither was exactly perfect at keeping out the elements. Certainly not as wind- and rain-proof as Volkswagen’s Beetle Cabriolet with its high quality folding roof. Okay, it sat inelegantly, pram-like, when folded, but it was this pragmatic approach from Germany that would see the soft-top Beetle make it right through until 1980. It subsequently inspired the Golf Convertible – with its inbuilt rollover bar helping keep the car as taut as the standard hatchback – that would kickstart a whole new convertible craze in the decade that really celebrated big hair, conspicuous consumption and, eventually, a much cleaner atmosphere…