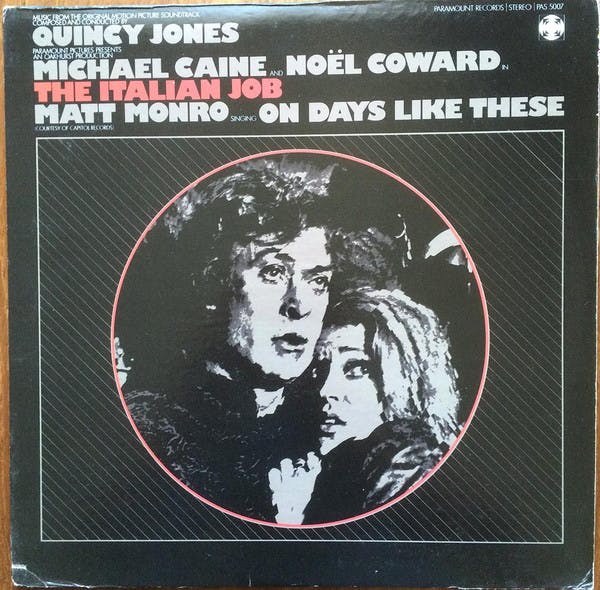

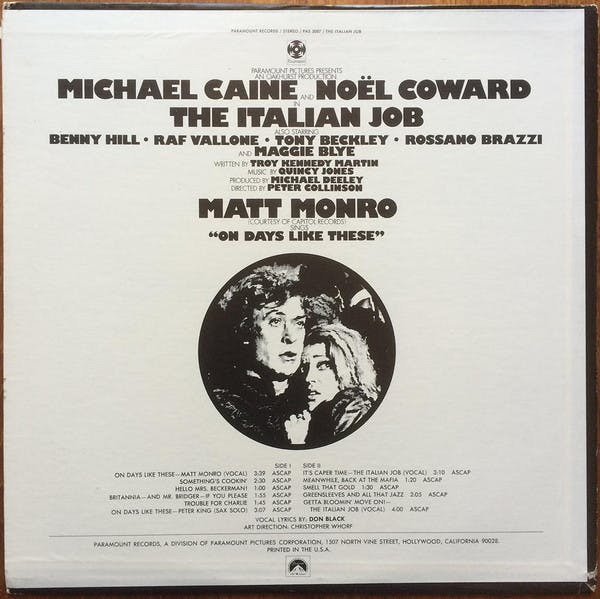

He worked with Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson. He sat at the centre of the recordings for the 1985 charity effort “We Are The World,” which sold more than 20 million singles. Over his career, he walked away with a Grammy Award more than 28 times, and he scored Oscar-winning movies. Having died at the age of 91 this week, the world looks over the long career of Quincy Jones with astonishment that in one lifespan he could create so much. Undoubtedly, he was one of the most influential music producers of our time. And if you’re a petrolhead, his masterwork was creating the soundtrack behind The Italian Job.

Now celebrating its 55th anniversary, the classic British crime caper remains one of the most thrilling and inventive films of the late 1960s. Sure, Bond had his gadgets and his tuxedo, but wouldn’t you rather root for a bunch of cheeky ne’er do wells and their plucky Minis? “The only way to get through it is we all work together as a team,” quips Michael Caine’s fictional Charlie Croker, “and that means, you do everything I say.”

Now let’s chant it all together: You’re only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!

But behind the great stunts, scenic locales, and memorable cast – both human and automotive – is a literally pitch-perfect kaleidoscope of a soundtrack put together for this most English of films by a guy who grew up on the South Side of Chicago. Quincy Jones liked to tell a story about a young Elton John describing the song Get A Bloomin’ Move On (popularly known as the Self Preservation Society). Only a Brit could write that score, quoth Elton. “You wanna bet?” replied Quincy.

That song, which is featured in the trailer and closes out the film, is peppered with authentic Cockney rhyming slang, some of which is sung by Michael Caine himself. It’s the kind of detail you wouldn’t expect from a relatively young American producer who had grown up collaborating with jazz greats like Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. Still, Jones had uncanny ears and a magpie’s fascination for understanding style and applying it as the situation needed.

Take, for instance, The Italian Job’s memorable opening sequence: a Lamborghini Miura navigating the switchbacks of the Alps. If you’ve got grease under your fingernails, nothing could sound sweeter than Giotto Bizzarrini’s V12 masterpiece, but Jones created a swelling ballad that pairs perfectly with the Italian scenery like a well-crafted Chianti. This despite the song’s singer, Matt Monro, being born in London and going by Terence Parsons offstage.

On Days Like These and Get A Bloomin’ Move On are the two lyrical songs on The Italian Job soundtrack, supported by a host of instrumental music that adds drama, tension, and sometimes comedy to the scenes. Jones spun groovy Sixties organ music with folk influences and a chirrupy harmonica, and even managed to make a mandolin sound sinister when we’re checking in to see what the mafia are up to. Criminal kingpin Mr. Bridger, Noel Coward’s last performance before retiring, gets a harpsichord-infused theme that’s a riff on Rule, Britannia!. Everything’s just as it should be, even when you’re watching the action rather than listening closely.

The decision to hire Quincy Jones to score The Italian Job seems to have been made by both the film’s director, Peter Collinson, and its producer, Michael Deeley. The latter is something of a legend in British film, and also produced well-known hits like The Deer Hunter and Blade Runner. It was Deeley who made sure the Minis were the star of The Italian Job, and he did so despite getting basically no help from British Leyland. He was also clever enough to set the film in Turin, using a mutual connection to get the aid of Fiat’s Gianni Agnelli. Agnelli even offered to replace the Minis with Fiats, free of charge, but Deeley knew this wouldn’t work.

He also knew he had to have something special to tie together the film, especially its literal cliffhanger ending. With a kid on the way – his only son, Quincy Jones III – Jones was persuaded to come live in London with his family and record the soundtrack. He is said to have become obsessed with classic East End tunes, the cheery sort of slightly rude comical fare that Londoners could recognise from a whistle. It’s where the mischievous lilt of Get A Bloomin’ Move On came from.

Jones recorded the soundtrack for The Italian Job at Olympic Studios on Church Lane, a London studio graced by everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Queen. In fact, while Jones was directing his 44-piece orchestra during the day, The Rolling Stones were recording Sympathy For The Devil during night sessions. In interviews, Jones said that Michael Caine used to come to these sessions, charmed by a beautiful cellist in the orchestra. It was here that he got lessons on how Cockney rhyming slang worked.

The two men were to become lifelong friends, not just because they got along generally, but due to an incredible coincidence. During production, one or the other of them mentioned they had a birthday coming up in a week. So have I, the other one replied. It turned out that each was born on the same hour on the same day: 14 March 1933. On the news of his longtime friend’s passing, Caine’s statement called Jones “My Celestial twin Quincy,” the fond term the two often used to refer to each other.

Though he never owned a car or indeed actually learnt to drive, Jones thus left his fingerprints on car culture the way he did on the American songbook as a whole. He helped elevate one of the great heist movies to something truly memorable. Every time you watch Charlie Croker and his crew scamper across Turin, the carabinieri in their Alfa Romeos in hot pursuit, remember Caine’s Celestial twin. When you look at his 91 years on earth, Quincy Jones blew the doors off life – and then some.

Self preservation society’s LYRICS were write by Englishman, Don Black. As we’re On days like these. Nevertheless an excellent article. I didn’t know that Quincy and Michael Caine shared a birthday