Born in 1858, Rudolf Diesel was a polymath. Capable of bringing people to tears with his fine piano playing, he was also an artist, a social philosopher, and, of course, the engineer and inventor who turned theoretical thermodynamics into the most efficient internal-combustion engine still yet developed: The diesel engine. However, his life ended in suspicious circumstances: Made wealthy by his invention, and by all accounts still in love with his wife Martha, he either fell, jumped, or was pushed overboard and drowned while traveling by boat on 29 September, 1913, on the eve of World War I.

One reason why Diesel developed his compression-ignition engine was to give access to engine power to places in the world that didn’t have access to coal or petroleum. Diesel engines will run on just about any kind of oil, including vegetable and nut oils, as well as coal tar derived from coal and kerosene refined from petroleum.

In a recent book, The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel (Atria Books, 2023), author Douglas Brunt raises the possibility, also apparently raised at the time of Diesel’s death, that the inventor’s demise was not an accident: Either petroleum interests, i.e. billionaire John D. Rockefeller Sr, or international intrigue, i.e. Kaiser Wilhem II of Germany, were involved in Diesel’s disappearance.

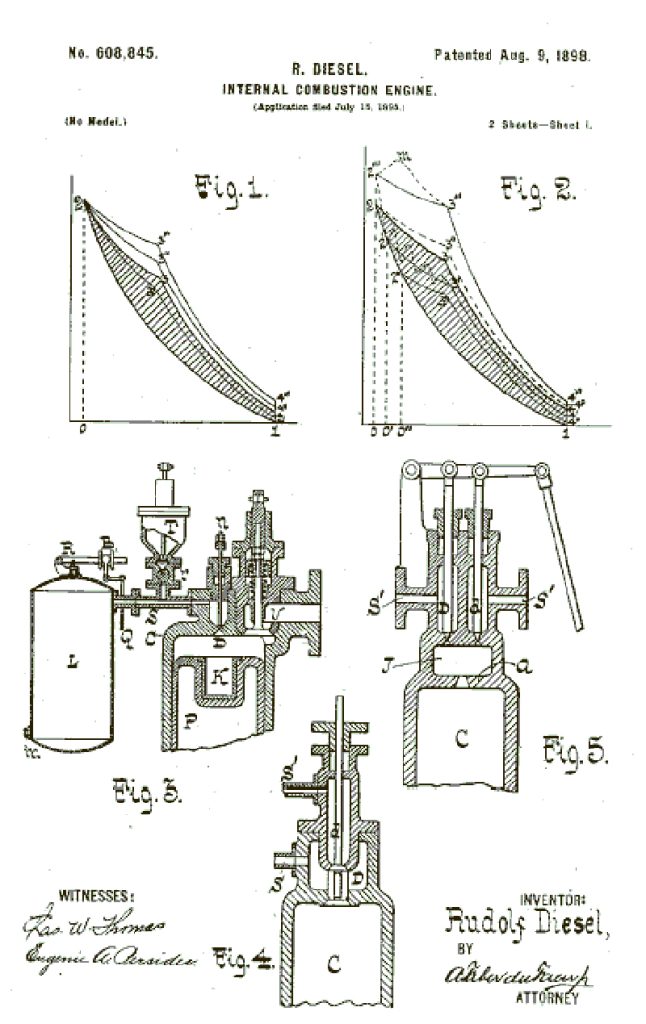

While the book seems to be a decent biography of Diesel, and covers the development of his engine without getting too technical, there are some nagging problems. I’m not convinced that Brunt really understands how piston engines work, though there’s a diagram of a four-cycle diesel in the book’s appendix. A couple of times Brunt refers to “driving the gears” of an engine, not of a transmission. That’s just a minor issue; there are greater problems with aspects of the book’s main premise – that Diesel was murdered by forces working for one of two powerful men – at least, when you consider one of those men and recorded history.

The Kaiser Wilhelm II part of the conspiracy theory is based on the fact that, by 1912, Diesel, who was ethnically German but partially raised in Paris, was unhappy with his original German partner/licensee, the MAN company of Augsburg, and was developing his technology to be used by Great Britain. In 1912, Diesel co-founded the Consolidated Diesel Engine Company in Ipswich and gave a speech in London about the value of diesel power to Britain – at nearly the exact same time that Winston Churchill, who was then in charge of the Admiralty, gave a speech about converting the British Navy from steam to diesel power. At the time, Wilhelm was challenging British sea power by growing the German navy, including a variety of diesel-powered U-boat submarines.

Early 20th-century geopolitics is not one of my fields of study, so I can’t really speak to the probability that the Kaiser made Rudolf Diesel sleep with the fishes, but I’m a bit more familiar with automotive history, and am better equipped to speak to the Rockefeller theory. To be frank, this theory reminds me of an urban legend, which holds that Rockefeller supported Prohibition because he didn’t want alcohol to replace gasoline as a fuel.

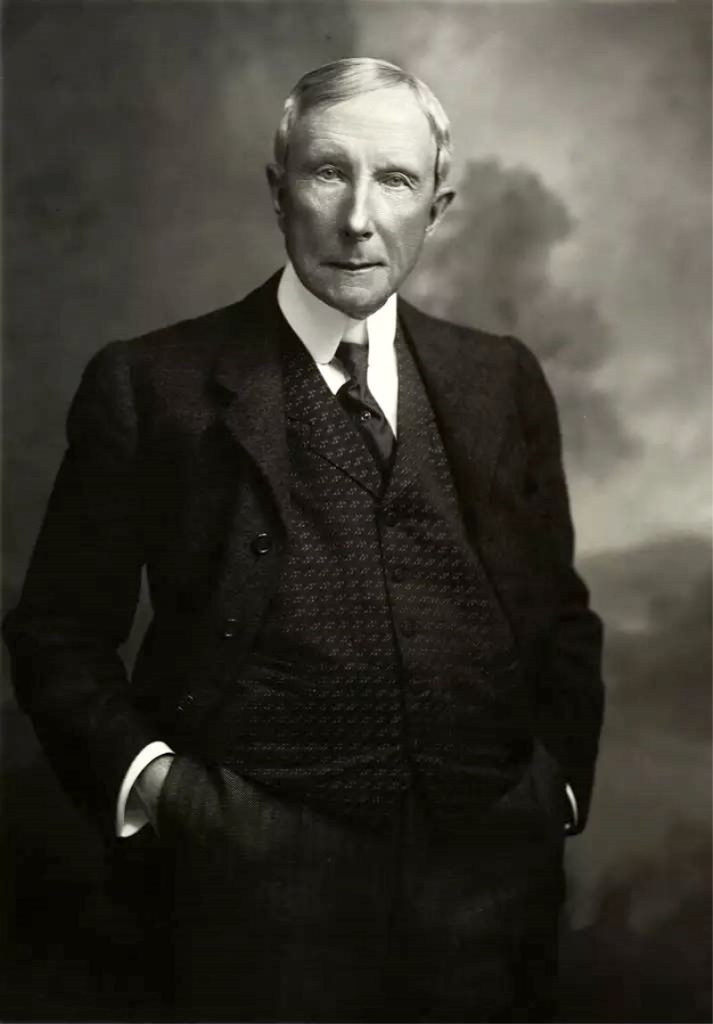

The Rockefeller part of Brunt’s argument is based on two successive and supposed threats – electric cars, then Diesel’s flexible-fuel engine – to Rockefeller’s business empire, which was based on his monopoly of the petroleum industry in America.

In the very early days of the automobile, steam and electric power did compete with gasoline, but by 1913 Stanley was selling fewer than 500 Steamers annually. EVs weren’t doing so hot either. None of the leading electric-car manufacturers were meeting anywhere near the production figures that Ford Motor Company, for example, was putting out in 1908, before the Model T was introduced.

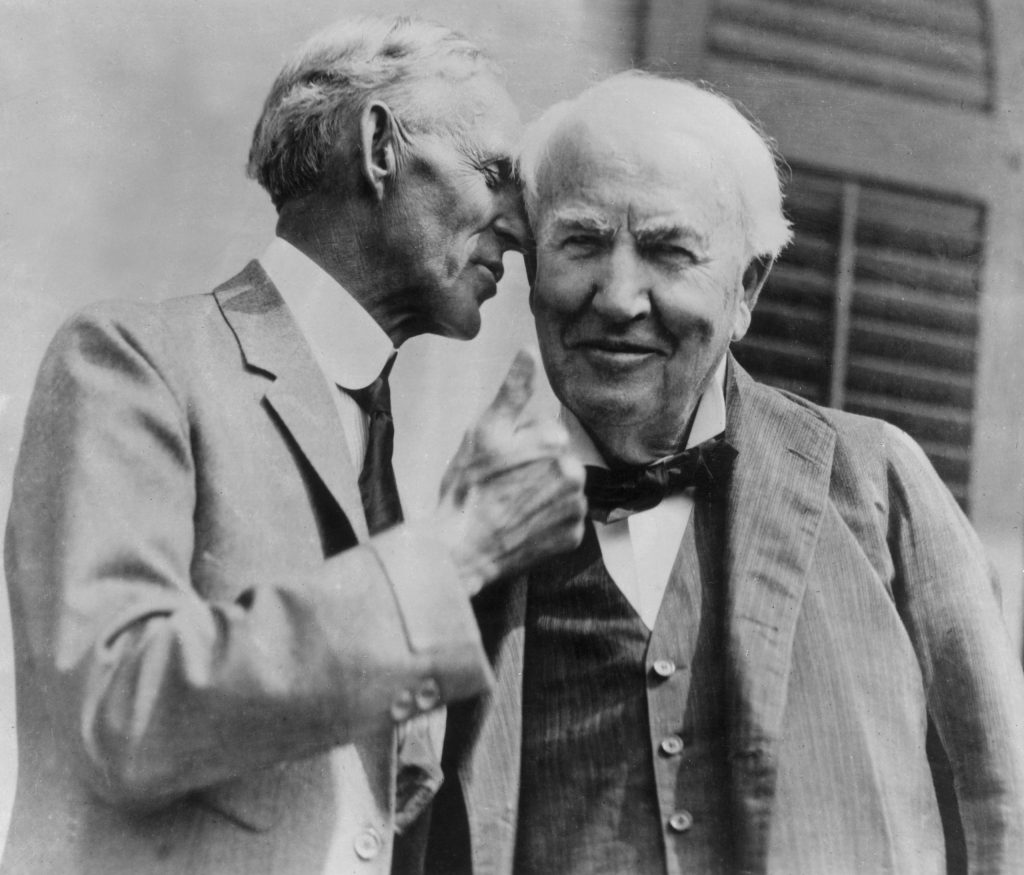

Electric cars, though, received renewed interest, at least for a little while, when Henry Ford invested about $1.5 million 1914-era dollars (nearly $43m / £34m today) into developing an electric Model T. Ford hoped that his friend and former employer Thomas Edison’s new batteries, which used nickel-iron chemistry, would prove to be practical for use in EVs.

Brunt attributes the failure of Ford’s attempt to mass-produce an electric version of the Model T to a “mysterious” fire at Edison’s plant in West Orange, New Jersey. Brunt strongly implies that the fire could have been the work of the Pinkerton detective agency working for Rockefeller. The connection between the agency and Rockefeller isn’t far-fetched: Part of the Pinkertons’ notorious reputation was gained working as union-busters for Rockefeller. The argument that the fire doomed the electric Model T, though, is shaky.

The Ford-Edison electric Model T failed because Ford’s engineers couldn’t get it to work well enough in Detroit, not because of any mysterious fire in New Jersey. To begin with, Edison’s storage battery plant and R&D lab were not damaged in the fire, and the electrified Model T was developed in Michigan, not in New Jersey; Edison simply supplied the cells. Ford had already bought 100,000 or so batteries for the project, more than enough for the few prototypes that were made. Low energy-density and long charging times, the same challenges EV batteries face today, doomed the project: When Henry found out his R&D team had replaced his good friend Edison’s batteries with conventional lead-acid cells to improve the car’s performance, he killed the project. That was very much like Henry Ford: When all of the FWD Miller-Fords DNF’d at Indy in 1935, Henry killed the program. He didn’t like being embarrassed.

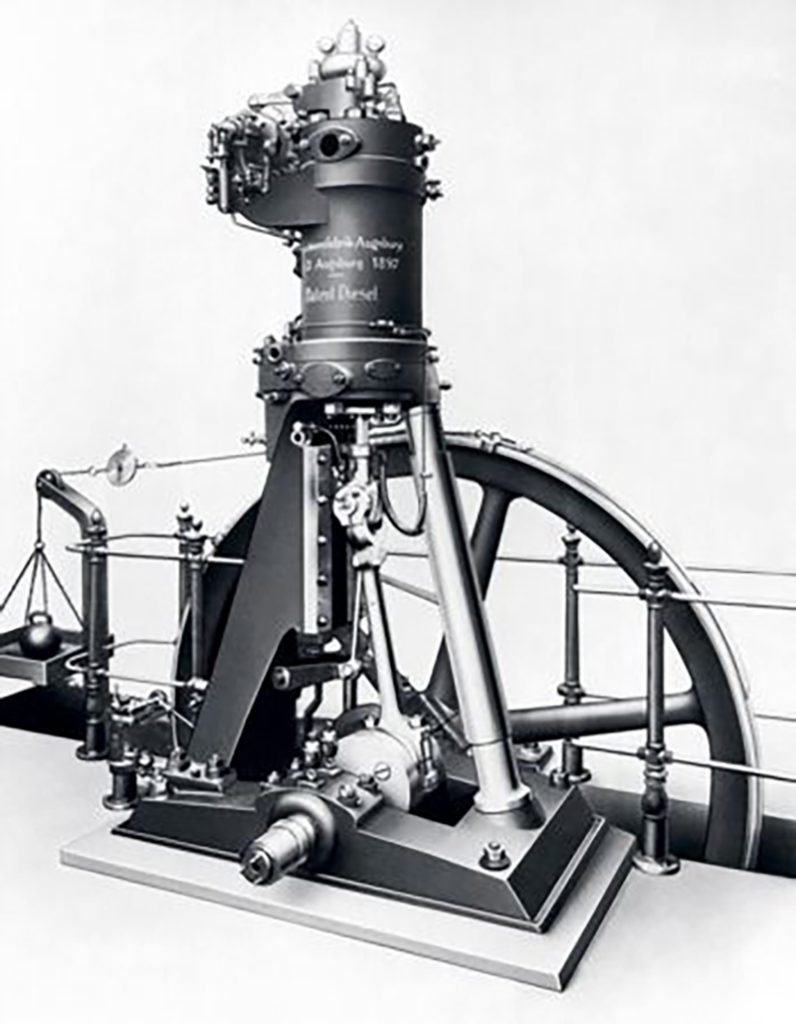

Soon after Ford abandoned the EV effort, Brunt says that the automaker swung the market towards combustion cars by cutting the T’s price to $500. Charles Kettering’s development of the electric self-starter further cemented the dominance of ICE cars. According to Brunt, though, after Ford’s actions supposedly killed off early EVs, Rockefeller’s interests were threatened once again, by Diesel’s engine because it could run on plant and other combustible oils, and therefore did not rely exclusively on kerosene. Brunt is quite right about the flexibility of Diesel’s design: When Diesel first demonstrated the first fully operational prototype, his third engine, in 1897, it ran on peanut oil. But what Brunt overestimates is the market’s ability to supply alternative fuels, like plant oils, in sufficient quantities.

Rockefeller originally established his market dominance by selling kerosene and natural gas for lighting. Edison and Westinghouse changed all that, of course, but the spark-ignited Otto cycle engine created a market for a not-very-useful byproduct of refining kerosene that was called gasoline. Rockefeller became even wealthier and more powerful. At the turn of the 20th century, as Diesel’s engine design was being licensed and proliferating as an industrial power source, Rockefeller already had a vertically integrated monopoly capable of producing and marketing either gasoline or kerosene. There was no similar industry set up to make and distribute plant oils on a massive scale.

With the investments needed at that time to manufacture those non-petroleum oils on an industrial level, there was no way that the development of diesel power for transportation would challenge the dominance of petroleum. In the century since then, as the use of diesel engines in transportation has spread globally, no country has embraced running engines en masse on anything other than petroleum-based fuels.

Also, the timeline doesn’t work out. Ford started hyping the electric T in late 1913, going public with announcements in early 1914, at a time when Ford Motor Company was already selling hundreds of thousands of cars annually. In 1913, FoMoCo sold over 170,000 Model Ts; the following year, it sold over 200,000. Henry didn’t need to lower to price of the T to dominate the market. True, when he lowered the price of a Model T Runabout from $525 in 1913 to $440, an 18 per cent drop in price, sales rose a proportionate 18 per cent. However, after Ford raised the price of the T from $345 in 1916 back up to $500 in 1917, sales went up by almost 47 per cent, a much more dramatic increase.

It’s hard to find production figures for early EV companies, but it appears that the best-selling electric car in the early automotive age was the Detroit Electric. Two widely divergent figures are cited for total production (1907 to 1939): 13,000 or 35,000 cars. Henry Ford may have invested the equivalent of today’s millions in an electric Model T, but when he did that, electric cars already made up a tiny percentage of the cars in use. Combustion engine cars were dominating the market long before Ford even tried making an electric Model T.

In addition, at the time of Diesel’s death, his engines hadn’t yet been adapted for use in personal vehicles. Though Rudolph Diesel originally envisioned his engine as a compact powerplant, in 1913, it was still being used to power industrial equipment or large ships. These were very large engines, in some cases the size of a small house. It wasn’t until the mid-1920s that Clessie Cummins developed the first practical and relatively compact diesel engines for road transportation – in his case, for over-the-road trucks, and not until 1936 did Mercedes-Benz introduce the first diesel-powered automobile. In 1913, no matter whether Rudolf Diesel drowned accidentally, committed suicide, or was murdered, John Rockefeller’s petroleum-based empire could not have been threatened by diesel-powered cars and trucks running on peanut oil or coal tar: There were no diesel-powered cars or trucks in 1913.

While Douglas Brunt tells a good story, it doesn’t appear likely that John Rockefeller actually had any motive to have Rudolf Diesel killed.

Herr Diesel did not invent the oil engine!!

Herbert Akroyd Stuart invented it. Don’t believe me…then Google it!

We should call those dirty beasts Stuart engines.

great story,but still money was and still is the root of all evil!!!!!!!