Author: Roland Brown

Photography: Roland Brown

In response to HDC member Mark Baron’s question via Ask Hagerty, Roland Brown has created a guide on how to get into classic bike collecting.

It’s Sunday lunchtime in a village pub car-park in the Cotswolds, and the view is of a sea of classic motorbikes. All are Laverdas from the Seventies. Most have orange paintwork; many are the 981cc, three-cylinder Jota that was among the fastest and most famous superbikes of the Seventies.

My lunch amid old motorcycles a day earlier could hardly have been more different. The Donington Park paddock had been crammed with roaring, snarling racebikes of all ages, sizes and nationalities, from AJS and Matchless singles from the Fifties, via Yamaha two-strokes of the Sixties and Seventies, to Ducati V-twins, Honda V4s and Suzuki GSX-Rs from the Eighties and Nineties.

This typical August weekend in the Midlands encapsulated the vibrant world of classic motorcycling. The Saturday scene was the Classic Racing Motorcycle Club’s flagship Festival, featuring bikes competing on Donington’s Grand Prix circuit. The following day’s event at The New Inn in Willersey was a reunion to mark the 50th anniversary of the Jota, Laverda’s most famous model, aimed at owners of the mighty Italian triple.

“Where’s the best place to start to get into classic motorbikes?” a member of the Hagerty Drivers Club recently asked. As those two examples show, the answer could be pretty much anywhere – and you won’t be short of options, depending on what type of old bikes you like, and what you want to do with them.

Literally the best place to start is probably an event, of which those mentioned above are just two of hundreds held throughout the year. Finding one to attend within reasonable range shouldn’t be difficult. The classic two-wheeled world is well served by magazines, notably Classic Bike, Classic Bike Guide and Classic Mechanics in the UK, plus RealClassic and The Classic Motorcycle for slightly older machines; and Motorcycle Classics in the States.

The publications list upcoming events, ranging from race meetings, sprints and hill-climbs to owners’ club gatherings, festivals and museum open days. There are some excellent museums, notably the National Motorcycle Museum in Birmingham and the Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum in Hampshire, where a visit can be enhanced by themed days for certain marques or models.

Shows are a good place to get inspiration from a broad range of bikes and retailers. Britain’s two biggest are both held at the Staffordshire Showground: the International Classic Motorcycle Show in April and the Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Show in October.

A race meeting is ideal if you’re drawn to the two-stroke rasp of a Yamaha TZ350 being warmed up, the chattering of a Ducati V-twin’s dry clutch, or get misty eyes (rather than just a twitchy nose) from the Castrol R smoke that hangs in the air as the Manx Nortons and other old British singles take to the track.

The action is frequently just as exciting as with modern machines, thanks to a broad range of classes designed to generate close racing. The Classic Racing Motorcycle Club runs events under five main age categories, dividing bikes produced all the way from 1945 to 1994, with those built since 1973 being known as “Post Classics”.

In some classes, riders also have to be older than 55. This encourages a mix of generations, from grey-bearded veterans who’ve raced the same bike for decades, to young guns aboard machines built long before they were born.

The ultimate race meeting is the Classic TT, held in late summer in the Isle of Man on the same Mountain Circuit as the main TT meeting in June. It’s a great time to visit motorcycling’s Island. The roads and hotels are less busy than in June but the racing can be just as thrilling and the atmosphere is just as magical.

Another historic venue is Belgium’s Spa-Francorchamps, where the Bikers’ Days festival draws an array of old bikes. America’s best-known celebration of old bikes is the Barber Vintage Festival, held on the circuit that sweeps through the grounds of the spectacular Barber Museum in Alabama. Some of the Museum’s stellar cast of bikes are put through their paces on the circuit from time to time.

In the UK, classic motoring enthusiasts can get an introduction to two wheels at the annual Goodwood Revival, where the bike events are always hard fought. Goodwood’s Festival of Speed can be relied on to feature exotic factory racebikes being caned up the hill by similarly illustrious former champions. For those who prefer a slower pace, events include the historic Banbury Run, an annual outing for pre-1931 machines.

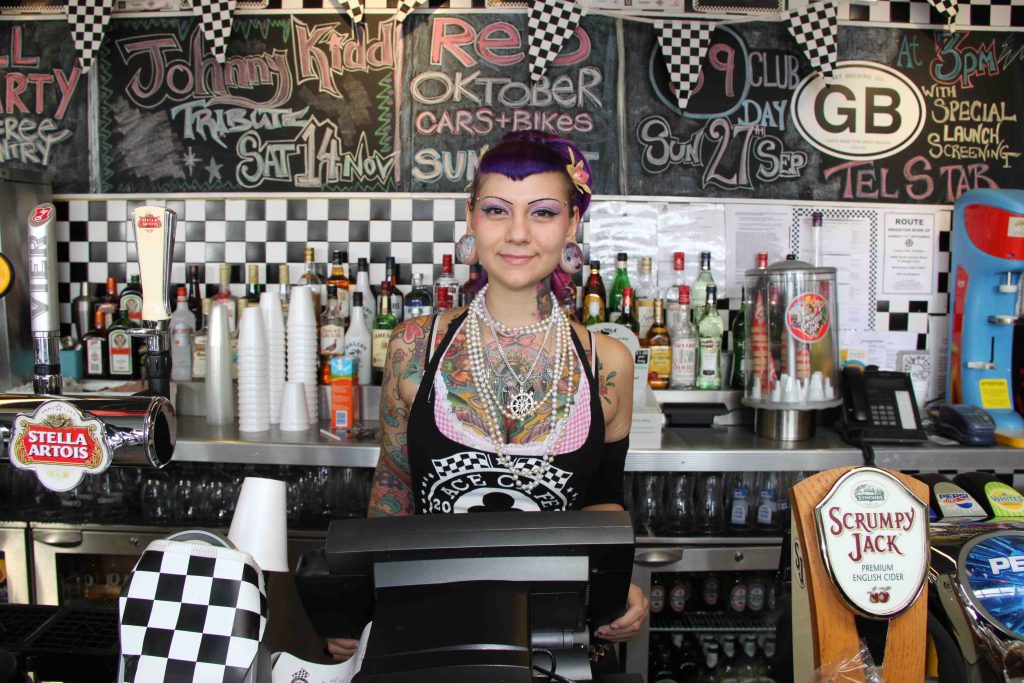

Many motorcycling meeting places host themed gatherings that incorporate classics. The Ace Cafe in north London, famous haunt on the leather-jacketed Rockers in the Fifties and Sixties, holds a regular Vintage and Classic Bike Day, as well as evenings for Seventies bikes and classic scooters.

The Ace also serves as a starting point for annual “reunion runs” to the coastal resorts of Southend, Margate and Brighton, where Rockers fought with the scooter-riding Mods in the Sixties. Few of the original participants are young enough to attend these days but their spirit lives on. Memories are rekindled by shiny-tanked Triton cafe racers and mirror-adorned Vespas and Lambrettas.

At most of these events you can check out the bikes and talk to their owners for the price of a beer or burger. Alternatively, you could just take the plunge and buy a classic. If you’re planning to do that, you probably don’t want advice on which model to choose – because you’ll already have decided, based on your experiences decades ago.

“Generally, the bikes people buy are what they rode when they were younger, or what they wanted to ride,” says Chris Bunce, who has run Hampshire-based Classic Superbikes for more than 15 years. “It’s usually a decision made with the heart, not the head.” But you do need to think carefully about what you’re buying, and why.

The days of people buying classic motorcycles as investments are over, says Bunce, whose stock ranges from exotic Manx Norton racebikes, via Triumph parallel twins and Ducati V-twins to a 175cc BSA Bantam and several sports mopeds from the Seventies. “Prices of many classics rose for 15 years but have fallen back in the last five, pretty much to where they were before.”

Many of the old-school enthusiasts who kept the classic British bike scene vibrant in recent decades are now too old to ride. Others are choosing similarly styled but more rider-friendly modern retro bikes such as BSA’s new Gold Star or Royal Enfield’s softly tuned singles and twins.

“People buying classics these days tend to be enthusiasts, not investors,” says Mike Davis, motorcycles expert at auctioneers H&H Classics. “Prices are the lowest they’ve been for a while but the positive thing about that is that it attracts new people who might not have considered a classic before. And people are still keen – we’ve had two auctions this year and sold 95 per cent of the bikes at each.”

A glance at the sold list from H&H’s auction in July shows a fascinating range of classics, many of which changed hands at dangerously tempting prices for anyone with a love of old machinery. At the top end were two immaculate looking Vincent V-twins that sold for less than £30,000 – a lot of money, sure, but much less than they’d have cost a few years ago.

At the other extreme, buyers picked up a BSA Bantam, Royal Enfield Bullet and Velocette LE – humble commuter models from the Fifties and Sixties – for around a grand, and some sweet looking single-cylinder Norton Model 7, Triumph T100 and Velocette Viper roadsters of similar vintage for roughly £3000.

Similar money can buy a lightweight Italian bike – typically 175 or 250cc singles from Ducati, Moto Guzzi or less well-known names such as Morini or Rumi. As well as being sweet and stylish, these can be used to tour their home land in a revival of the classic Motogiro d’Italia road race of the Fifties. There’s also a UK version, the Giro South West (aka the Three Moors Run), for similar small-capacity machines.

Nice examples of some of the most popular classics from the Sixties and Seventies, such as Triumph’s 750cc T140 Bonneville, Norton’s Commando 750 or 850 and Suzuki’s GT750 two-stroke triple, were selling for £6000 or £7000, when a few years ago they would have been nearer £10,000.

For many younger riders, some of the best bargains are big-selling models from the Nineties – now all over 25 years old, in much less demand, and still very capable motorcycles when running well. Decent examples of Honda’s VFR800F, Suzuki’s Bandit 1200 and Triumph’s T595 Daytona, for example, can be picked up for as little as £2000.

Even some of the stars of that era have down-to-earth prices. Classic Superbikes’ current stock includes two of the brightest, a Ducati 916 and a Yamaha YZF-R1, both from 1998 – in the R1’s case its first year – each available at under £8000.

Buying privately or at auction can land a bargain but involves risk, because you won’t be able to take it back. On the other hand, reputable dealers such as Classic Superbikes put machines through their workshop before selling, and offer some reassurance.

“Occasionally I’ll get a phone call from someone who’s bought a bike from me, and I’ll always help,” says Bunce. If something goes wrong we can fix it at reduced cost. I’ve never had an customer unhappy.” Dealers can also offer advice, some of which applies regardless of make and model.

“Buy the best bike you can afford, and if it’s been restored make sure you have the receipts,” says Davis. “Go for a bike that was registered new in the UK, rather than an import, if possible. Preferably one whose components are original, the especially exhaust system. Imports and non-standard bikes are generally worth less.”

Bunce suggests avoiding restored bikes altogether. “Lots of people love a mint-looking nuts-and-bolts restoration but they can be nightmares. There’s not enough money in it for professional restorers to do the job properly, so they cut corners. And private restorations can be great but many amateurs don’t have the skills. We spend half our lives undoing what’s been done to restored bikes.

“I’ve learned the value of a barn find. They generally have all the right parts in the right places. Ideally you’d want a bike that’s been in regular use. I’ve got a Honda 500 four that I’ve owned since 1979. It’s not in mint condition but it’s all there, it’s all Honda. It feels like a proper 500 four.”

Bikes that have not been ridden regularly often cause problems – typically low-mileage classics, due to unused fuel causing rough running. “A Japanese four with carburettors is usually horrid if it’s been stored for any length of time. It’s typically been rebuilt with a pattern carburettor parts, usually from China.”

It’s also worth bearing in mind the challenges of riding an older machine. Values of pre-1930 “flat-tankers” (whose fuel tanks hung from the frame top tube, rather than running around it) have plummeted, due to ageing owners and reduced demand, and the lower prices have sparked fresh interest.

“We get some younger riders interested in pioneer bikes,” says Mike Davis. “Maybe their grandad did the Banbury Run and they fancy a go. These bikes can be rewarding but they have virtually no brakes and no clutch – many are single-speed and need pushing to start, so they’re not for everyone.”

You’ll also have to remember to adjust an ignition advance lever, and possibly to push a plunger every so often to add a shot of lubricating oil. Even more recent classics have idiosyncrasies. The ritual of “tickling” a typical old British bike’s carburettor to get the petrol flowing, then leaping on the kickstarter, is part of the experience of riding it.

Modern tyres can give a welcome improvement over original rubber, but few drum brakes can approach the stopping power of recent discs. Many bikes built before the mid-Seventies have rear brakes on the left and gearchange on the right – so an instinctive stamp of right boot will not help an emergency stop. Some gearboxes have a one-up, three-down pattern to further complicate matters.

A relatively recent, left-foot-change bike might therefore be a more suitable first classic. But for some riders, the “differentness” is a vital part of the appeal. After all, the very idea of riding an old bike, when you could ride a modern one, doesn’t make much sense. But when did common sense ever come into it?

Got a question you’d love us to answer? Drop your question here! We’ll be picking some of your submissions to feature in upcoming articles.