Words: Nathan Chadwick

Photography: Maserati

It’s an era that even its maker, until very recently, dared not mention. Even the Modenese hotel in which its architect called home for several decades has no mention of him. For many, Alejandro de Tomaso’s Maserati Biturbo was a failure, and a stain upon the brand – a cataclysmic failure that’s been copied and pasted onto every list of ‘crap’ cars.

The thing is, without the Biturbo, there would be no Maserati today. It could also be argued that its innovative approach to brand diversification would mean that many brands such as Porsche, Lamborghini, BMW M, AMG and even Ferrari might not be the financially secure brand pillars – and in some cases, nowhere to be seen.

It’s often argued that the Biturbo spoiled and ruined Maserati, usually by a certain brand of motoring journalists of the 1970s and early 1980s who regarded a supercar on their driveway each week as a birthright, let alone a perk of the job. The problem with that view is that it doesn’t have much to do with reality. This is important, because the Biturbo was a car born of very intense, violent socio-politics through much of the 1970s and beyond – particularly in the land of its birth. At the time, Italy was being ravaged by terrorists on either side of the political spectrum, but the left’s view of conspicuous consumption, particularly with regards to cars, could lead to Semtex enema. This might seem at odds with a country obsessed with motorsports and the construction of supercars, but it’s worth remembering that to this day Italy doesn’t trouble the top five sales markets.

Part of that problem was not just the prospect of waking up with your legs and clutch pedal several hundred yards from the rest of your exotic road car, but of government taxation. Cars above 2.0-litres were taxed punitively, which gave rise to such oddities as the Ferrari 208 Turbo, and Italian-market versions of the E30 BMW M3.

As a result of all this – plus the hangover from the 1973 fuel crisis – was that Maserati sales had withered to a trickle. Alejandro de Tomaso needed to do something fresh and different to save the company, and turned to an experience from his Pantera days. While thrashing out the details with Ford on a trip to California, he noticed that the hip young things of the surf scene were not driving the same lightweight, largely British sportscars their parents had fell in love with during the post-war years – instead, small sporty saloons from BMW and Alfa were far more en vogue. Seeing an opportunity, he saw the potential for a two-door saloon that offered all the performance of something exotic, but with a more sombre image. This would open up Maserati to a much bigger audience and bigger sales; at the time, the firm wheeled out cars in the hundreds. The Biturbo would take that into the thousands. To make his idea work, he turned to GEPI, an government-backed investment fund designed to keep workers working.

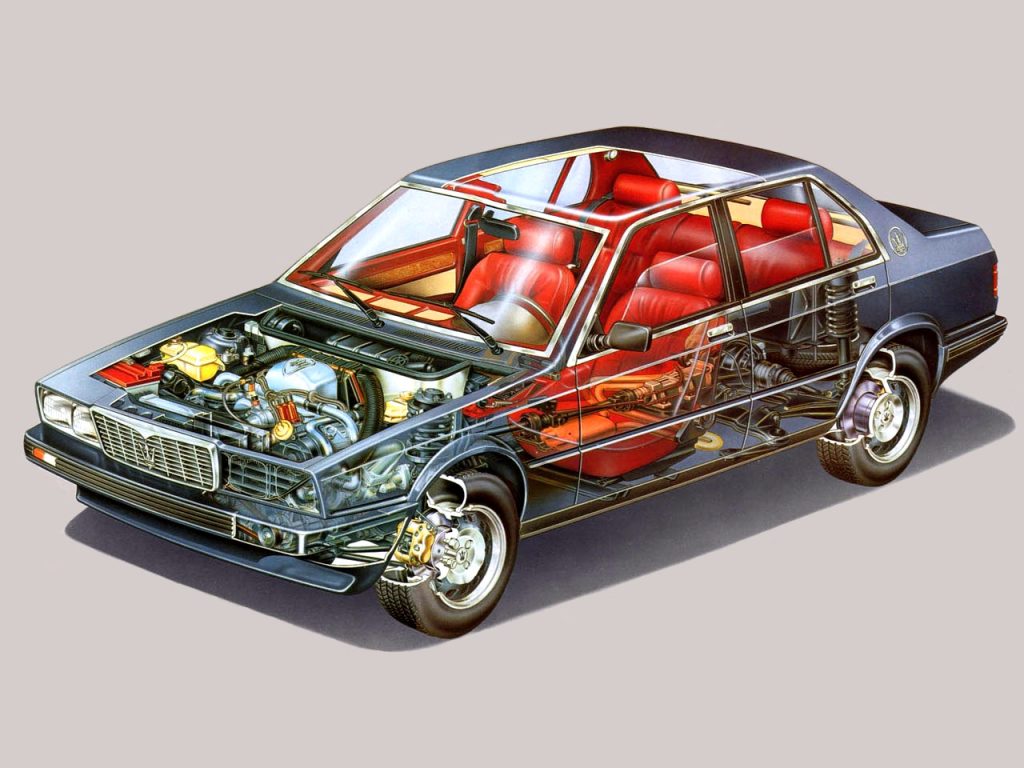

Then he turned to Giorgetto Giugiaro to essentially use the DNA from his Quattroporte III design and apply it to a 3-Series-sized shape. Giugiaro declined (somewhat forcefully, according to legend), which meant Pierangelo Andreani styled the car.

Despite the disgust of those English-writing car hacks that believed Maseratis should only make supercars and if not, go bust, the car was an absolute hit. The world’s first twin-turbocharged production car offered luxury and performance in an appealing package. Sales reached 40,000 per year to begin with… but there were problems.

It took four years for Andreani’s sketches to become production reality, and GEPI demanded their money back as soon as possible. This didn’t leave a lot of time for proper productionisation, and led to early reliability problems – hot starting issues being the key issue, but somewhat challenging handling, rear screen heater malfunctions and poor rustproofing were also present. In the key US market, with all its lemon laws and parts supply issues, the car quickly became tainted.

Now, if the car’s life ended there, with those very early carburettor-fed cars, then the criticism the Biturbo still gets subjected to would be justified. However, the introduction of fuel injection and continual improvements into the ‘number cars’ that replaced the tainted Biturbo name, and the later Ghibli II, really improved the car and most of the issues that plagued the car were immediately fixed – but sadly, the reputation stuck.

Nevertheless, reliability, fit and finish and performance continued to grow, all the way to the Ghibli Cup – its 2.0-litre V6 pushed out 325bhp, the highest output per litre of any road car at the time of its 1996 launch.

The fuel-injected Biturbos (and its descendants) offer great performance compared to their rivals – compared to an E30 or E28 BMW, arguably the closest comparisons, they’re often far more powerful and torquey. Later cars also benefited from upgraded diffs and suspension components that made them much more amenable to use. They’re still not for the faint-hearted, particularly in export market form – Italian-market cars tended to have more power from their 2.0-litre engines. Export markets had bigger displacements and more torque, further down the rev range. A recipe for interesting moments in a car without traction control and, for the most part, without ABS.

This is the essential crux of the Biturbo-era cars’ appeal – they’re so much more special to be in than an equivalent BMW. The plush leather interior smells sweet in the way only an Italian car can, and is styled beautifully. Early cars even had Missoni provide its cloth finishing. Then there’s the performance – Biturbos really do feel exciting to drive in a way a sober-suited BMW only reveals in the M cars. And they are worth many tens of thousands more.

However, the biggest appeal nowadays is the way they look, particularly the Marcello Gandini-styled cars – the number cars of the late 80s and 90s, the Ghibli II and the thunderous V8 Shamal. Each of these cars are now bang on trend for the sharp-suit brutalist cars, which has seen cars such as the Alfa Romeo SZ and Lancia Delta Integrale rocket in value. A Gandini-era Biturbo car will set you back a fraction of those, yet will offer more rarity and adrenaline.

The Biturbo may have got off to a poor start but look beyond the negative press and you’ll see a sharp-suited, engaging car that’s truly different – for those that dare to stray from the herd mentality.

What are your thoughts on the Maserati Biturbo? We would love to hear from you at hdc@hagerty.co.uk