Author: Nathan Chadwick

Images: Alfa Romeo/Nathan Chadwick

Whatever your views on the way Alfa Romeo has fared since it was absorbed into the Fiat family in the mid-1980s, the first decade or so produced some entertaining, engaging cars that resonated with the buying public in a major way.

Cars such as the GTV 916 and 156 were immensely popular – there were even waiting lists for the latter. However, the very early days of the Fiat/Alfa union didn’t go too smoothly.

Though the 164 and 75 had done well for Alfa, replacing the ageing 33 would prove to be more of a challenge. It may not be the most fondly remembered Alfa nowadays, but it’s one of the few from the brand to sell more than one million examples. A fact made more remarkable in that it was essentially an updated, simplified AlfaSud platform.

The purchase of Alfa Romeo had been rather forced on Fiat – the loss of such an iconic brand to Ford, as had been mooted in the early 1980s, was something that couldn’t be countenanced. Fiat simply had to buy Alfa Romeo – the problem was, its model portfolio was dated, other than the 164, and the entire range needed revamping.

The problem was that it came just as Lancia was being geared up for a 1990s renewal. As successful as the Delta Integrale had been in rallying, underneath it was a Ritmo/Strada Abarth with a turbo, while the Delta itself dated back to 1979. Again, an entirely new range for the 1990s needed to be developed.

As such, Lancia and Alfa Romeo development programmes were worked on together at Fiat Centro Stile under the direction of Mario Maioli. Ermanno Cressoni, Enrico Fumia and Walter de Silva would report to him, with an international design team crafted in-house options.

The new Delta would share its DNA with the 33 replacement – the recently launched, and immensely successful, Fiat Tipo. The Alfa, led by Cressoni, would be styled to be sporty, while the Lancia, led by Fumia, would be more conservative.

Chris Bangle, who would later go on to infamy with BMW, was working in the Lancia department. As he would prove in Munich, Bangle was unafraid of thinking differently, and had designed a forward-thinking five-door hatchback.

The story goes that once everyone had gone home, Maioli was wandering around Centro Stile and happened across Bangle’s full-sized plaster model. He asked Cressoni what it was, who explained. “It looks more like an Alfa to me…”

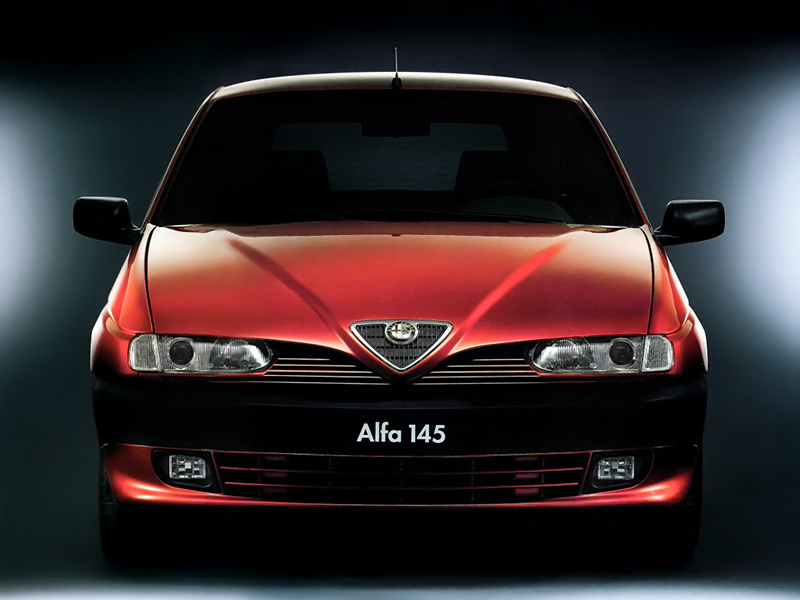

Thus the 145 was born. You can see elements of Lancia design language in the car even today – the front headlamps look a little similar to the 1990s Nuovo Delta, while the square back with wraparound glass echoes the Lancia Y10 Turbo. It was a truly modernist design, with plenty of fascinating features – just look at the way the window line drops down on the doors, the kicked-up bumper mouldings, the aggressive nose (and suggestive grille placement).

Bangle travelled between Alfa and Lancia’s design studios refining the design, losing two doors for the 145 and pushing out the front wings to give it more than an Alfa look. The 146 was developed without Bangle, and was perhaps somewhat less modern-looking – then again, the four-door saloon market was far more traditionalist anyway.

The resulting car was strikingly different to anything else on the road, and polarised opinions – but the response was generally positive. However, the 145’s big problem was that there weren’t enough four-cylinder engines to go around the group, so for the first two years of its life it soldiered on with the Boxer engines that made their debut in the Sud nearly two decades earlier. Though characterful engines thanks to their raspy sonic theatrics, the galvanised Tipo platform was a lot heavier than the 33; they felt somewhat underpowered.

The range-topping Cloverleaf (known as the Quadrifoglio in Europe) appeared in late 1995 with a 2.0-litre Twin Spark four-cylinder engine from the GTV 916, along with that car’s fast steering rack (2.2 turns lock to lock). With 150bhp, it was certainly up there with the fastest hot hatchbacks at the time… but that time would be fleeting.

The 146 had made its debut in May 1995, and got the Cloverleaf’s engine in 1996, and was called the ti, a nod to the sporting Alfa saloons of the 60s. A year later, the Boxer engines were withdrawn from sale and replaced with 1.4-litre, 1.6-litre and 1.80-litre Twin Spark engines.

In 1999 the range was facelifted, with body-coloured bumpers and upgrades to the interior – well, if you were anywhere else but a right-hand-drive market. We carried on with the slab-slided, distinctly 80s-looking interior until it was replaced with the 147 in 2001.

The 145 occupies a strange place in the history of Alfa Romeo. It sold 500,000 in six years, but now survives in tiny numbers. It’s a car that deserved more attention from its maker when it was in production – it really was a groundbreaking piece of design, of a kind that the Ford Focus later aped. The car didn’t benefit from much in the way of ongoing development, particularly the sporting models – the 306 GTI-6 moved the hot hatch arms race on, and had a much more modern, comfortable interior. It also had a six-speed gearbox, all the better to get the best out of its 167bhp. The range-topping Cloverleaf carried on with the 150bhp four-pot and five-speed box right until the end.

Alfa did produce a prototype with a 190bhp 2.5-litre Busso V6 engine, but time ran out (probably just as quick as the front-end grip) – however, that development work would roll into the 147 GTA.

Now the 145 is starting to be recognised as a quirky modern classic, with values rising as a result. However, the appeal is more about the looks and the sheer character of that Twin Spark engine. Though it’s not all a bed of Cloverleafs…

Owning a 145 Cloverleaf

I have rather a soft spot for the 145 Cloverleaf – I own one. I’d always been a fan of the 145’s cheeky personality, so when I saw my car at Autosportivo getting on for eight years ago I loved it. Finished in red with black 155 five-spoke alloys, it looked every bit the hot hatch hero I never got to experience as an adolescent. It had a sprinkling of aftermarket goodness that made it handle far sharper than any other 145 I’d driven. I loved it, and desperately wanted it.

I didn’t have the money at the time, so it was sold. It would return to Autosportivo a few years later, its sump having been ripped off on a kerb. Ant from Autosportivo fixed it, and then sold it again – it had even been given a fresh coat of paint.

Fast forward five years, to 2023, and I was walking around the Festival of the Unexceptional with my wife. She caught me staring at a 145, and uttered the immortal words : ’ooh, that’s nice, don’t you fancy one of those’. Before we’d even reached the car park on the way home, I was on eBay bidding on the very car I’d fallen in love with all those years ago. It was true serendipity, and I won the auction.

It was in a bit of a state when Ant and I rescued it – there was clear daylight in the sills, and the paintwork was distinctly secondhand. Third gear was worn – it kept popping out – and there it needed love.

In the couple of years it’s had plenty of that – a replacement gearbox, new engine mounts, refreshed suspension and a lot more. It nearly owes me significant multiples of its £700 purchase price… but I can’t help but love it.

Yes, the Peugeot 306 GTI-6 is the far superior car from a handling point of view, and for the money I’d dropped on it I could have picked up a Renault Clio 172/182 Cup. However, there’s something very endearing about the 145 – where the Frenchies only reveal their brilliance when being clobbered hard, the 145 is endlessly amusing almost everywhere. It’s loud, proud and zesty, and even if it’s not quite the handling hero the French cars are, it’s still bags of fun.

I even love the much maligned old-school interior – the Tonka toy buttons and slabby plastic have a coolness of their own, and do without the horrible soft-touch plastics that afflict my 147 GTA.

It’s not perfect – you sit on it, rather than in it, which coupled with a lack of lateral support means that hard cornering can mean you slide into the passenger footwell/tweak your sciatic nerve, delete as applicable.

Sadly, the car’s Achilles heel has hit – the Twin Spark engine is wonderfully characterful, with a high-revving roar and a surprisingly useful midrange, but it has a critical flaw. The bottom end is weak and engine failure goes some way to explaining why less than 100 are left these days. As I type this, it’s sitting in my garage awaiting the funds for a fresh engine – its third – in 165,000 miles.

It’ll be worth it, though. Come 6000rpm with the new engine, it’ll be a proper Alfa… just as design chief Maioli deemed back in the early ‘90s.

What are your thoughts on the modernist marvel above? We would love to hear at hdc@hagerty.co.uk.