Author: Roland Brown

Photography: Roland Brown

Riding Suzuki’s RE-5 is a unique experience, even before you start the rotary engine that makes it special. When you turn the key in the ignition, the cylindrical instrument console’s plastic cover flicks back to reveal the dials and warning lights – a striking feature now, let alone half a century ago.

When I pressed the starter button, the motor fired up with a low burbling sound, feeling every bit as smooth as I’d expected of the world’s first rotary-engined superbike. Moments later I was cruising along, gripping the Suzuki’s wide handlebars and enjoying the feel of this most distinctive and rare of Seventies machines.

Well, enjoying most of it, anyway, because the RE-5 was running roughly at high revs, spluttering with some sort of carburation problem – sadly, an issue all too typical of the model that Suzuki had boldly launched in 1974, a year before this example was produced.

Large, shiny, curiously shaped and lavishly equipped, the rotary seemed like a machine from a different world back then. Rarely has a motorcycle stood so far from the mainstream with its blend of innovative engineering, complexity and performance.

Suzuki had unveiled the RE-5 (generally with a hyphen in its name, but also known as the RE5) at the Tokyo Show in late 1973. The rotary promised to combine the quality and some of the looks of the firm’s GT750 two-stroke triple with an exciting new engine that offered superior smoothness and sophistication. And in some respects it did just that.

Back then, many people regarded rotary engines as a coming force. German engineer Felix Wankel had begun experimenting with rotary valves for torpedo engines during World War II. During the Fifties the technology had been adopted by NSU, and several car manufacturers had produced engines.

German motorcycle firm DKW’s simpler, aircooled 294cc rotary, the W2000, appeared at almost the same time as the RE-5. Norton was also developing a rotary bike, and Dutch firm Van Veen had unveiled an exotic 100bhp rotary-engined superbike, the OCR1000, that would eventually be built in very small numbers.

The “big four” Japanese manufacturers were all taking rotaries very seriously. In 1974 Honda was testing a prototype called the CRX, Kawasaki was working on a bike code-named the X-99, and Yamaha had a twin-rotor machine called the RZ-201, which was almost ready for production.

But it was Suzuki who were leading the way. The firm had obtained a rotary licence from NSU in 1970, and had set a team of engineers to work on a prototype that was initially named the RX-5, standing for Rotary eXperimental, 500cc.

It was typical of the Japanese industry that, while DKW and Norton had chosen to develop relatively simple, aircooled motors, Suzuki attempted to get round some of the traditional problems of rotary engines by using innovative and complex engineering.

You’ll probably be familiar with the way that, in a Wankel rotary engine, power is produced by a near-triangular rotor, which spins around a central shaft inside an oval chamber. By comparison with a piston engine, the rotary has potential advantages of simplicity, smoothness, fewer parts and less weight.

But inevitably rotary technology was much less well developed than its piston-engined equivalent. The engine designers’ work included solving rotary-specific problems relating to ignition, carburation and cooling, as well as providing an efficient seal for the tips of the spinning rotor.

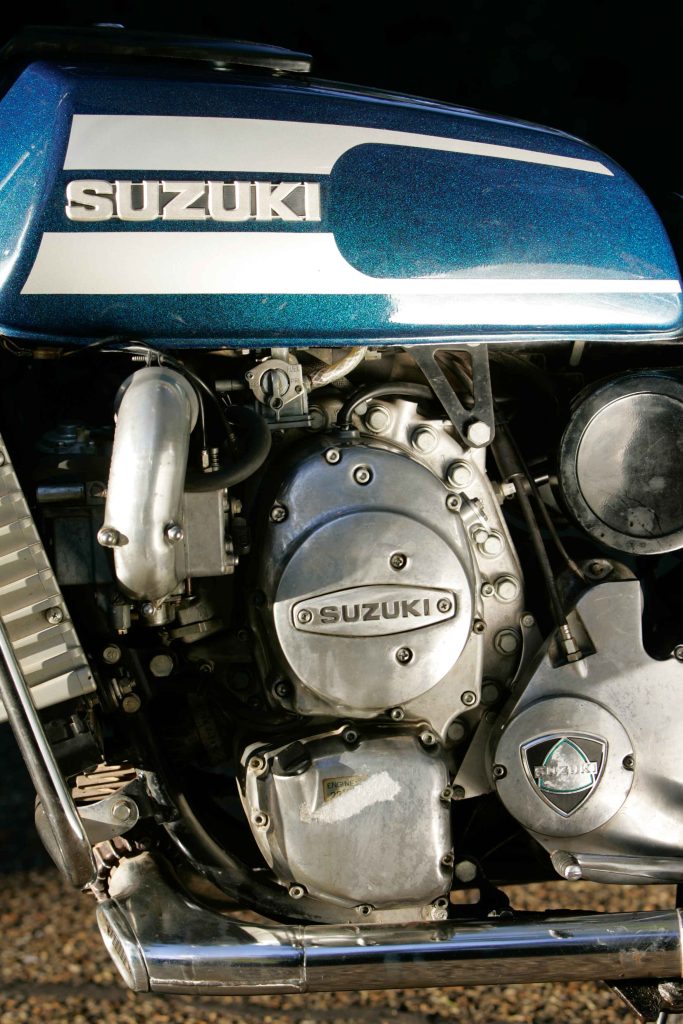

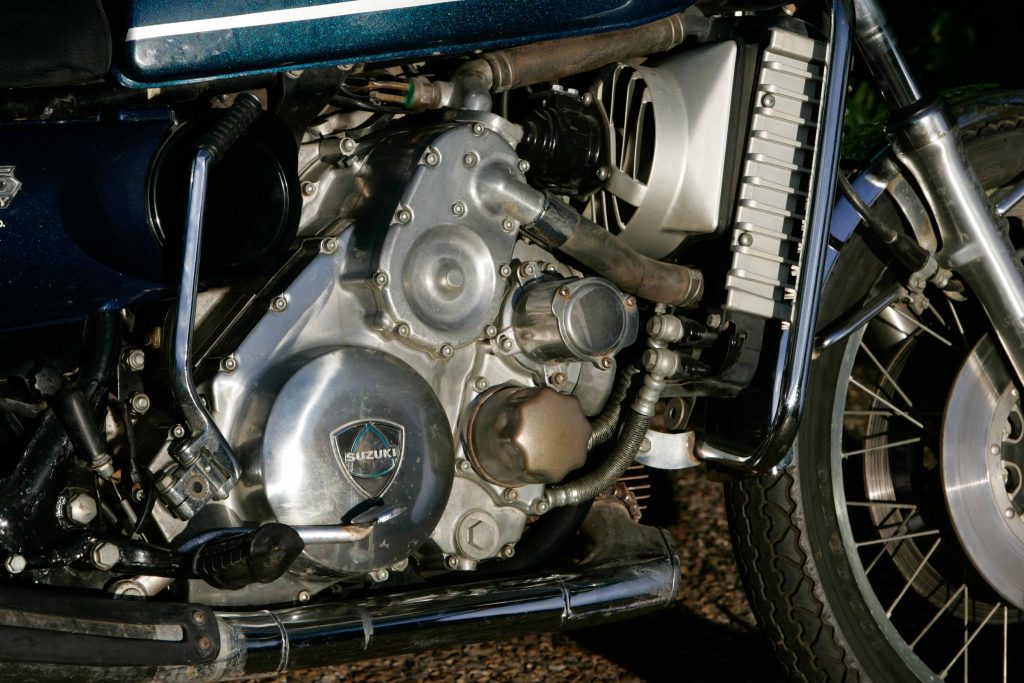

While Norton and DKW were opting for simplicity, Suzuki took the opposite approach. Norton’s 588cc rotary had twin rotors to the 497cc Suzuki’s one, but the British engine was aircooled, used conventional Amal carburettors, and had a normal ignition system and lubrication system. By contrast the RE-5 had two cooling systems, a two-stage Mikuni CV carburettor, two lubrication systems and even two ignition systems.

Suzuki’s approach did make sense, in some respects. The complex twin-choke carburettor, for example, was used in an attempt to provide good power at both low and high revs. Trouble was, it was big, heavy, complex and required no fewer than five cables.

The sophisticated ignition system was designed to improve engine performance when the throttle was shut; a typical rotary weakness. Another problem area, the rotor tips, was addressed by supplementing the normal lubrication set-up with a separate, two-stroke style system that fed oil into the combustion chamber with the fuel/air mixture.

Cooling of a Wankel motor can also be difficult, due partly to the long and narrow combustion chamber, so the RE-5 backed up its liquid cooling system with oil-cooling for the rotor. This was effective but added yet more weight and complexity. So too did the bike’s novel “double-shell” exhaust pipe, which passed exhaust gas through an inner pipe, while feeding cooling air through an intake at the front of the outer pipe.

The result of all this technology was a powerplant that produced a claimed 62bhp at 6500rpm, which was very respectable from an official capacity of 497cc. (Albeit the capacity of a rotary engine can be measured in various ways.) But it was less impressive compared with the 739cc two-stroke triple unit of the GT750, which made 67bhp at the same revs and was lighter as well as much simpler.

At least the RE-5 provided some welcome glitz and style, despite the unattractive look of the motor itself, surrounded as it was by pumps, fans and pipes. Suzuki were rumoured to have commissioned legendary car designer Giorgetto Giugiaro to shape the RE-5. Its fuel tank was slim and attractive; the cylindrical instrument panel and rear light neatly echoed the rotary theme.

This unrestored Suzuki’s instrument panel face, beneath that spring-loaded cylindrical cover, was plastic and slightly smeared. But in most respects the bike was was in fine condition, having covered barely 15,000 miles. Its chrome and alloy had lasted well, and there were just a couple of minor scratches in the blue and silver paintwork.

The bike initially ran well, too, as I headed southwards out of London. At 230kg dry it’s a heavy machine, but was slimmer than I’d expected, and reasonably easy to manoeuvre despite its tall seat. The wide handlebars helped, as did the smooth low-rev carburation, which suggested that at least some of Suzuki’s engineers’ efforts in that direction had been worthwhile.

Performance was very respectable by mid-Seventies standards, if not outstanding. Contemporary tests recorded the top speed at about 110mph, slightly down on the GT750’s; the standing quarter-mile time of about 14.5 seconds was about a second slower than that of the triple. But predictably the RE-5 was every bit as good at high-speed cruising, thanks partly to the smoothness of its engine.

Despite being solidly mounted in the twin-downtube steel frame, the rotary lump generated very little vibration throughout the rev range, apart from a slight tingle through the fairly forward-set footrests at about 4000rpm. But another typical rotary engine trait was less welcome: fuel economy. The RE-5 generally managed only about 30mpg, which meant the low fuel light came on after as little as 70 miles.

Even the best efforts of Suzuki’s engineers hadn’t cured that old rotary problem of inefficient fuelling, and that complex two-stage Mikuni carb also made life difficult when the bike needed servicing. So it was no great surprise that, decades later, this bike’s carburation was distinctly rough at high revs.

The Suzuki tended to stumble and misfire when the tacho needle indicated much above 4000rpm. The bike hadn’t been run for a while, which might have contributed to the problem. Even so, getting it running sweetly all the way to the 7000rpm redline was likely to be no easy job.

At least the Suzuki handled pretty well – a relief given that contemporary reviews were decidedly mixed. Motorcyclist in the States rated it the best-handling Japanese superbike so far. Bike in the UK praised its “comfort and confidence on motorway hauls” and its excellent high-speed stability.

The same rider enjoyed cornering the RE-5 on dry roads in Wales, where “it was fun to hustle the massive bike through the curves”, where it would “sweep through bends with a grace you’d hardly expect from such a lump of machinery”. But he also warned that: “Get it wrong and you’re in a real mess. Find yourself on the wrong line and the bike starts bucking and weaving when you try to put things right.”

Given its age, this bike was commendably well behaved. My main impression was of a big, comfortable tourer that felt a bit soft and wallowy, but was enjoyable provided I didn’t try riding it too aggressively. It was capable of fairly quick cornering on smooth roads, and had enough ground clearance to make good use of its Dunlop tyres.

Slowing down was a different matter. The twin-disc front brake illustrated just how much systems have improved. It felt wooden and underpowered, yet was highly rated when new, apart from the dangerous wet-weather delay typical of Japanese disc brakes at the time.

The RE-5’s overall performance, style and engine design were enough to cause plenty of excitement when it was launched. But when faced with the prospect of actually buying one, most European riders tended to agree with that Bike magazine tester’s conclusion that: “The Suzuki gives you a lot of very complex machinery for your money, which is OK if you want complexity and technical sophistication for its own sake.”

Most motorcyclists didn’t – at least, not for the price Suzuki was asking, which in the UK was £1195. That meant the rotary was over £300 more expensive than the quicker and slightly lighter GT750, and cost barely £50 less than Kawasaki’s mighty 903cc Z1 four, which was about 25mph faster and far more economical.

The rotary was better received in the touring-oriented US market, but even there it was not a success. Suzuki lost many orders after a technical glitch forced them to postpone delivery from October 1974 to the following January. Worries about possible unreliability were then magnified by a carburettor problem that forced a recall of all the bikes sold so far.

Rumours spread and interest fell. Sales did not improve sufficiently when the RE-5 was restyled for 1976 with changes including a more conventional instrument panel and tail light. By the end of that year, Suzuki had abandoned production, despite the huge amounts of time and money they had invested in the project.

The other Japanese firms quietly dropped their own plans for rotary-engined roadsters. DKW and Norton soldiered on with small numbers of bikes. But motorcycling’s rotary revolution was effectively over, less than three years after the RE-5 had begun it.